VIEWS OF NATURE

ALEXANDER VON HUMBOLDT

Translated by Mark W. Person

Edited by Stephen T. Jackson and Laura Dassow Walls

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS

CHICAGO AND LONDON

Stephen T. Jackson is professor emeritus of botany and ecology at the University of Wyoming. Laura Dassow Walls is the William P. and Hazel B. White Professor of English at the University of Notre Dame. Mark W. Person is associate academic professional lecturer in German in the Department of Modern and Classical Languages and director of the language lab at the University of Wyoming.

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2014 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. Published 2014.

Printed in the United States of America

23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-92318-5 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-92319-2 (e-book)

DOI: 10.7208/chicago/9780226923192.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Humboldt, Alexander von, 17691859, author.

[Ansichten der Natur. English]

Views of nature / Alexander von Humboldt ; translated by Mark W. Person ;

edited by Stephen T. Jackson and Laura Dassow Walls.

pages cm

Includes index.

ISBN 978-0-226-92318-5 (cloth : alk. paper)ISBN 978-0-226-92319-2 (e-book)

1. Natural history. 2. Science. 3. Physical geography. 4. South AmericaDescription and travel. I. Jackson, Stephen T., 1955 II. Walls, Laura Dassow. III. Person, Mark W. IV. Title.

QH45.H82 2014

508dc23

2013050786

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

Contents

Preface

This volume represents an unlikely professional intersection between a natural scientist and a humanities scholar. It is no coincidence that our professional paths crossed while pursuing the thinking of Alexander von Humboldt, who integrated these now-remote fields two centuries ago. And we were preadapted to find ourselves at this intersection: if not for a few chance events and influences, each of us could have spent a life pursuing a career in the others field of studyrespectively ecology, and American literature and history.

The book arose from our mutual recognition that Humboldts Ansichten der Natur represented a uniquely important and influential component of his oeuvre, linking the sciences and humanities in his most personal and passionate published writings. We also shared a hunch that the two existing English translations, both published in 184950, took Victorian liberties with Humboldts prose and didnt do justice to his vision or to his artistry. All these views were reinforced as the translation proceeded, and our appreciation of Humboldts intellectual riches steadily expanded as we read each chapter anew as it arrived from the translator.

We had the extraordinary good fortune to enlist the interests and talents of Mark Person, a gifted scholar of early nineteenth-century German literature and culture, in taking on the translation. Mark embraced the project from the start, and his fine ear for the beauty as well as the content of Humboldts prose is apparent throughout the translation. Comparing his translation with the two previous English versions, we couldnt help but think that he was scraping a mask of thick, sometimes garish Victorian paint off a profoundly beautiful piece of art. The translation will speak for itself, but we think that it may be as close to an embodiment of Humboldts voice as we may see in the English language.

The University of Chicago Press continues to set the publishing standards in the history of science and has committed itself to a series of Humboldt translations and related works. We thank Christie Henry for her continuing enthusiasm and support for our Humboldt and related projects, and we look forward to seeing more of his important works become broadly available.

Progress on the translation and editing took a great leap with support from the Ucross Foundation. The editors and translator spent a week in residence at Ucross, which provided not only wonderful working spaces, accommodations, and meals but a splendid, inspirational landscape. It was thrilling to read Humboldts accounts of the Rocky Mountains and Great Plains while situated among the smoking hills at the foot of the Bighorn Range.

Humboldt often expressed a feeling of being awestruck in the face of nature. We share those feelings, and experienced them daily in the landscape at Ucross and the nearby Bighorns. The spectacular skieswhether clear in day or night, colorfully clouded at dawn and dusk, or violent with thunderstormsprovided steady reminders of natures power and grandeur. But we were also awestruck at the breadth, depth, and splendor of Humboldts writings. We hope that the reader will share these feelings and that this translation will bring to a twenty-first-century audience a greater appreciation for the scientific aestheticthe sensual, emotional, and spiritual elements underlying our pursuit of knowledge of the world in which we find ourselves.

In preparing this volume, we made a deliberate, pragmatic decision not to add further explanatory footnotes and appendices. We determined that doing full justice to the work, particularly the rich, fine-textured footnotes, would require a near-doubling of the volumes length and a gargantuan scholarly effort. Instead, we chose to let Humboldts words speak for themselves, without annotation beyond our brief introductory essay, which aims to orient the reader and draw attention to the significance of the volume. Views of Nature is sufficiently important and manifold that it deserves a companion volume updating and explicating the footnotes, and perhaps also a critical companion volume, setting the core essays in context and exploring the countless themes they raise. We hope this translation and accompanying essay will reawaken Humboldts vision for the unity of science, knowledge, and human experience.

Stephen T. Jackson

Laramie

Laura Dassow Walls

South Bend

Introduction: Reclaiming Consilience

LAURA DASSOW WALLS, STEPHEN T. JACKSON MARK W. PERSON

I. The Writing of Ansichten der Natur

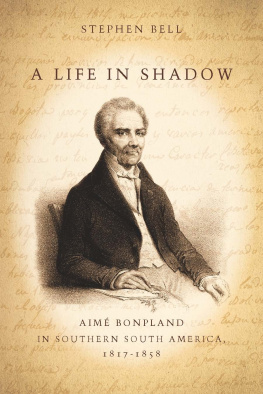

One of the ironies of Ansichten der Natur, Alexander von Humboldts most popular book and always his favorite, is that this seven-part hymn to the consilience of art and science, conceived in the tropics, was born in the bitter cold of conquest and defeat. In 1799, Humboldt had left Paris with his French traveling companion, the botanist Aim Bonpland, on a journey of scientific discovery to the New World. In 1804 the two had returned triumphantly to Paris, laden with enough specimens, measurements, notes, and insights to launch the old inquiries of natural history into the new sciences of the modern world. When they left, France had been a young republic, and wherever they traveled, from Venezuela all the way to Peru, to Cuba and Mexicowith a final stop in Washington, DC, to compare notes with Humboldts hero, Thomas Jeffersonthey had seemed to find new republics in the making, only to discover on their return that the French Republic had collapsed into imperial monarchy. But Paris was still the scientific center of the world, and Humboldt stayed long enough to enjoy being lionized before heading to Italy to visit his brother Wilhelm (then the Prussian minister to the Vatican), then finally, late in 1805, returning home to Berlin.

There he was welcomed, of course, but he also faced harsh accusations that he had lost touch with his German roots and been so entirely absorbed in French culture that, it was rumored, he planned to write up his scientific results not in German but in French. Humboldt in turn complained bitterly of the cold and the isolation of Berlin, which, he confessed, was a foreign land to me.less than two weeks later, Napoleon marched into Berlin at the head of an occupying army. The king and his court, on which Humboldt depended for his patronage, fled; the Prussian bureaucracy, in which he had himself been trained, collapsed; food prices soared, and many starved as the war reparations demanded by the French crippled the economy. The Humboldt estate at Tegel was looted, and most of the familys possessions were lost or destroyed. Berlin had fallen, and Prussia, Humboldts homeland, had effectively ceased to exist.

Next page

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).