ALSO BY ANDREA WULF

Chasing Venus: The Race to Measure the Heavens

Founding Gardeners: The Revolutionary Generation, Nature, and the Shaping of the American Nation

The Brother Gardeners: Botany, Empire and the Birth of an Obsession

This Other Eden: Seven Great Gardens and 300 Years of English History (with Emma Gieben-Gamal)

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

Copyright 2015 by Andrea Wulf

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Random House of Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Ltd., Toronto. Simultaneously published in Great Britain by John Murray (Publishers), a Hachette UK Company, London.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Wulf, Andrea.

The invention of nature : Alexander von Humboldts new world / by Andrea Wulf.First American Edition.

pages cm

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK T.p. verso.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-385-35066-2 (hardcover) ISBN 978-0-385-35067-9 (eBook)

1. Humbolt, Alexander von, 17691859. 2. ScientistsGermanyBiography. 3. NaturalistsGermanyBiography. I. Title.

Q 143. H 9 W 85 2015

509.2dc23

[B] 2015017505

Cover design by Kelly Blair

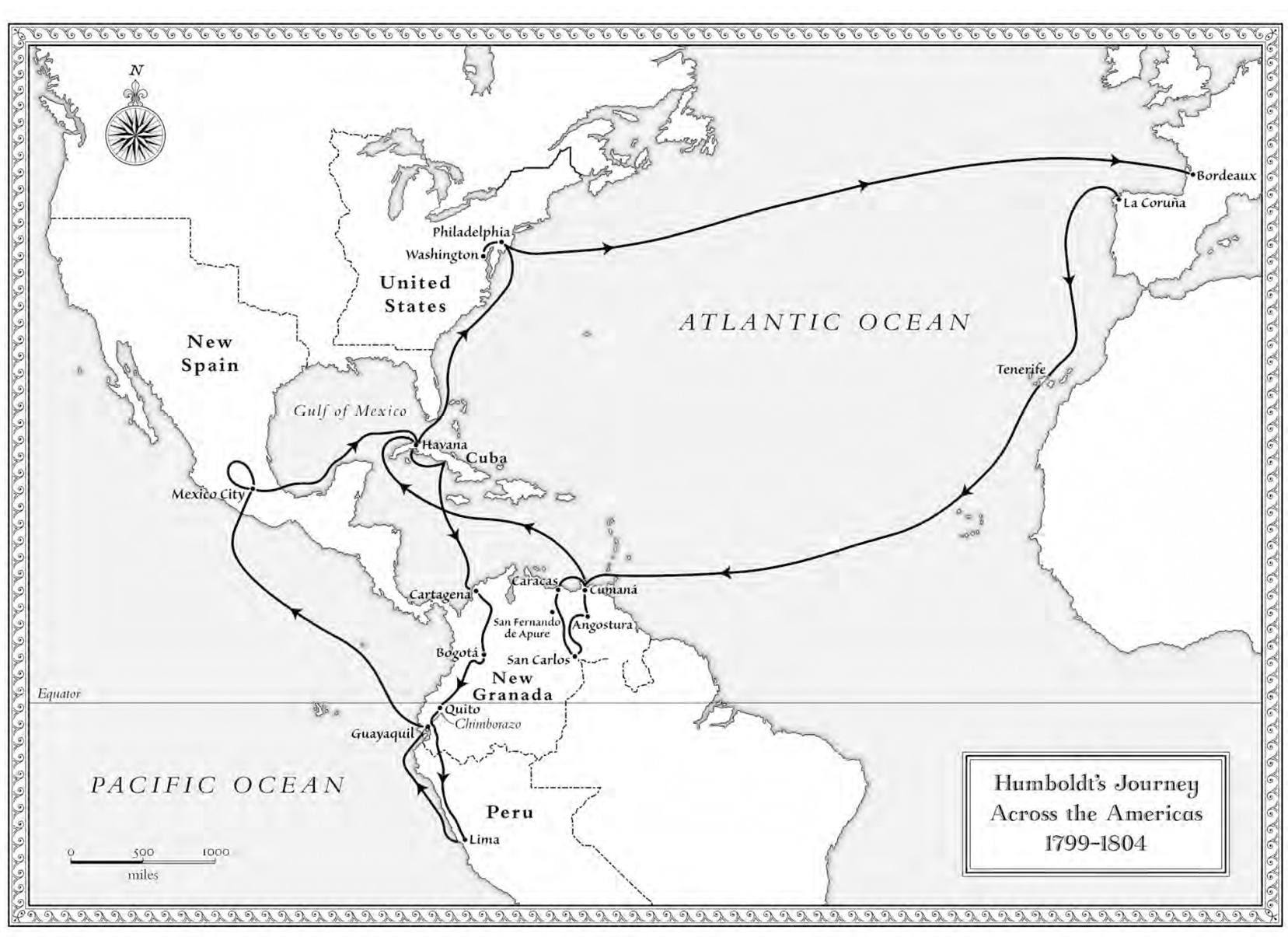

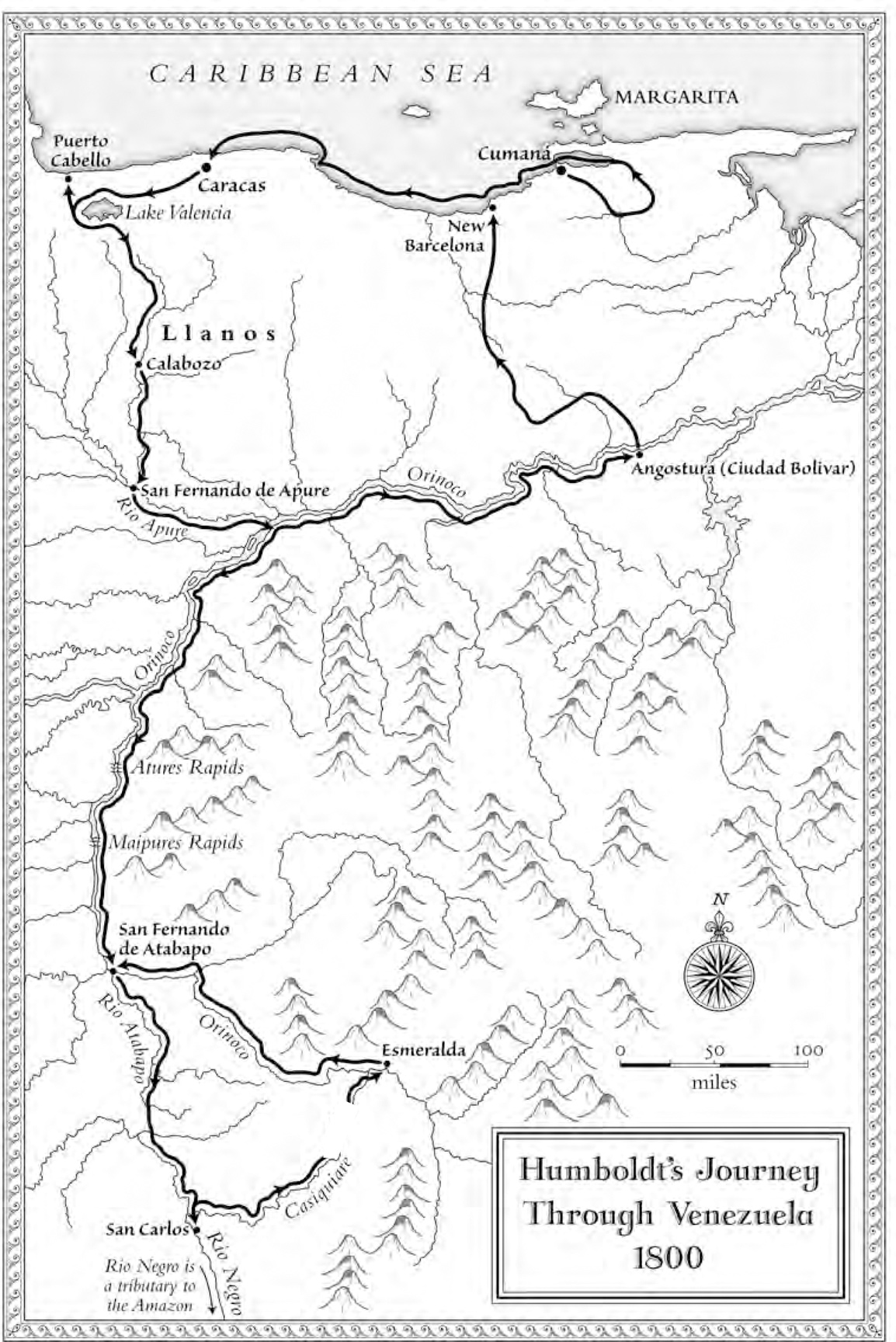

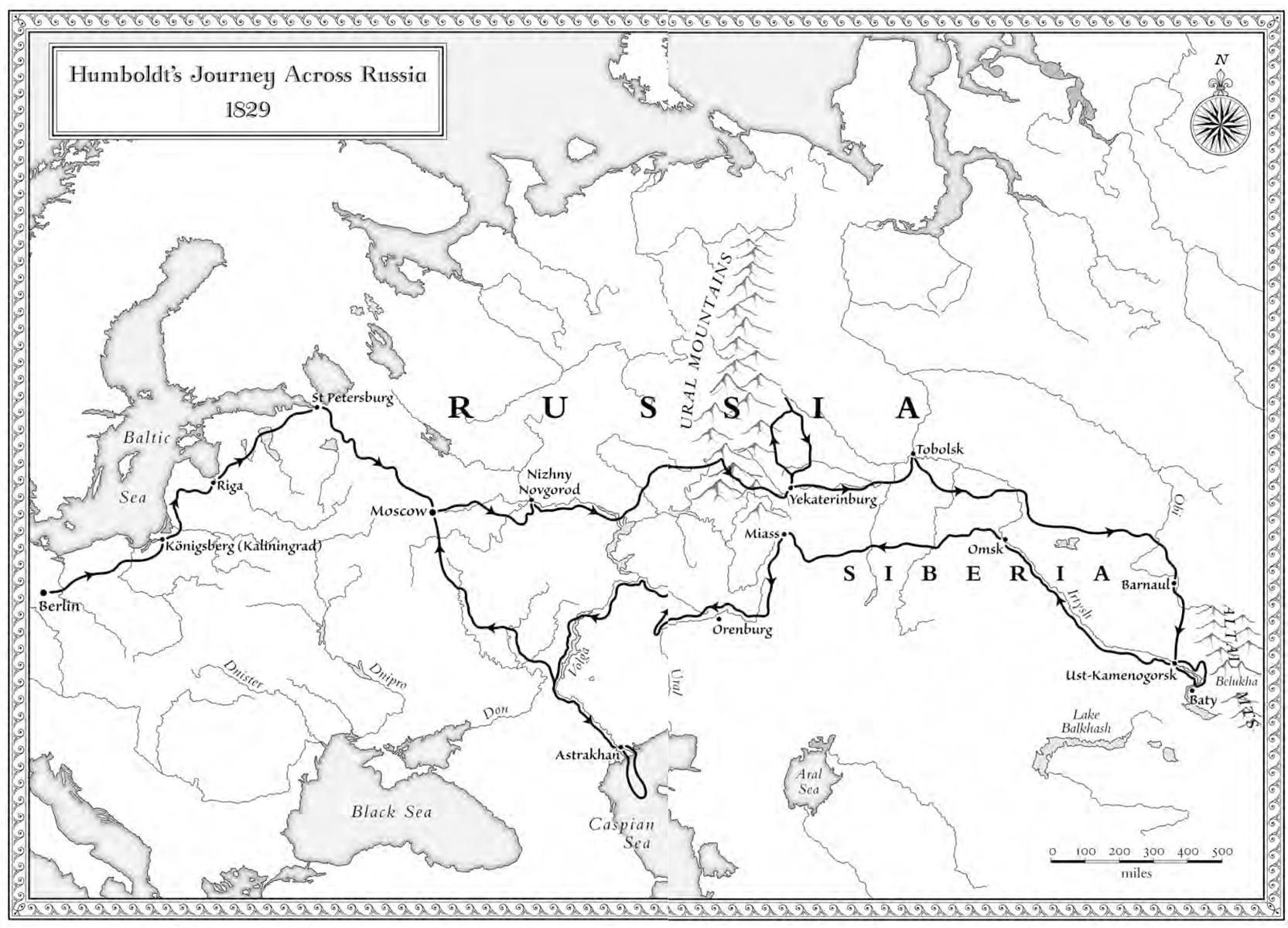

Maps drawn by Rodney Paull

v3.1_r3

To Linna (P.o.P.)

Close your eyes, prick your ears, and from the softest sound to the wildest noise, from the simplest tone to the highest harmony, from the most violent, passionate scream to the gentlest words of sweet reason, it is by Nature who speaks, revealing her being, her power, her life, and her relatedness so that a blind person, to whom the infinitely visible world is denied, can grasp an infinite vitality in what can be heard.

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Contents

Maps

Authors Note

Alexander von Humboldts books have been published in many languages. When quoting from his books directly, I have compared the original German (where applicable) and contemporary English editions. Where newer English editions have been available, I have checked those against the older translations and where I felt that the newer edition provided a better translation, I have chosen that version (details are in the endnotes). Sometimes neither translation captured Humboldts prose, or whole sentences were missing in which case I have taken the liberty of providing a new translation. When other protagonists referred to Humboldts work, I have used the editions that they were reading. Charles Darwin, for example, read Humboldts Personal Narrative that was published in Britain between 1814 and 1829 (translated by Helen Maria Williams), while John Muir read the 1896 edition (translated by E.C. Otte and H.G. Bohn).

Prologue

T HEY WERE CRAWLING on hands and knees along a high narrow ridge that was in places only two inches wide. The path, if you could call it that, was layered with sand and loose stones that shifted whenever touched. Down to the left was a steep cliff encrusted with ice that glinted when the sun broke through the thick clouds. The view to the right, with a 1,000-foot drop, wasnt much better. Here the dark, almost perpendicular walls were covered with rocks that protruded like knife blades.

Alexander von Humboldt and his three companions moved in single file, slowly inching forward. Without proper equipment or appropriate clothes, this was a dangerous climb. The icy wind had numbed their hands and feet, melted snow had soaked their thin shoes and ice crystals clung to their hair and beards. At 17,000 feet above sea level, they struggled to breathe in the thin air. As they proceeded, the jagged rocks shredded the soles of their shoes, and their feet began to bleed.

It was 23 June 1802, and they were climbing Chimborazo, a beautiful dome-shaped inactive volcano in the Andes that rose to almost 21,000 feet, some 100 miles to the south of Quito in todays Ecuador. Chimborazo was then believed to be the highest mountain in the world. No wonder that their terrified porters had abandoned them at the snow line. The volcanos peak was shrouded in thick fog but Humboldt had nonetheless pressed on.

For the previous three years, Alexander von Humboldt had been travelling through Latin America, penetrating deep into lands where few Europeans had ever gone before. Obsessed with scientific observation, the thirty-two-year-old had brought a vast array of the best instruments from Europe. For the ascent of Chimborazo, he had left most of the baggage behind, but had packed a barometer, a thermometer, a sextant, an artificial horizon and a so-called cyanometer with which he could measure the blueness of the sky. As they climbed, Humboldt fumbled out his instruments with numb fingers, setting them upon precariously narrow ledges to measure altitude, gravity and humidity. He meticulously listed any species encountered here a butterfly, there a tiny flower. Everything was recorded in his notebook.

At 18,000 feet they saw a last scrap of lichen clinging to a boulder. After that all signs of organic life disappeared, because at that height there were no plants or insects. Even the condors that had accompanied their previous climbs were absent. As the fog whitewashed the air into an eerie empty space, Humboldt felt completely removed from the inhabited world. It was, he said, as if we were trapped inside an air balloon. Then, suddenly, the fog lifted, revealing Chimborazos snow-capped summit against the blue sky. A magnificent sight, was Humboldts first thought, but then he saw the huge crevasse in front of them 65 feet wide and about 600 feet deep. But there was no other way to the top. When Humboldt measured their altitude at 19,413 feet, he discovered that they were barely 1,000 feet below the peak.