Wulf - Oeil Fauve

Here you can read online Wulf - Oeil Fauve full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 1995, publisher: Rodopi, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Oeil Fauve

- Author:

- Publisher:Rodopi

- Genre:

- Year:1995

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Oeil Fauve: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Oeil Fauve" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

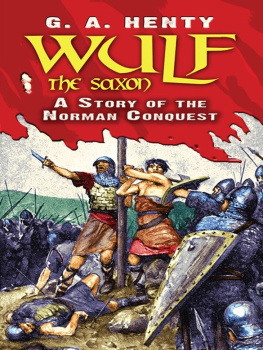

Wulf: author's other books

Who wrote Oeil Fauve? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Oeil Fauve — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Oeil Fauve" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

INTRODUCTION

Samuel Beckett's exploration of film and television roughly spanned the last two decades of his life. His first experiments with the visual arts (as distinct from his critical essays on modern painters) originated in 1963 when he wrote a non-verbal project which he simply called Film. With a one-man cast, and lasting about half an hour. Film takes its motto from Bishop Berkeley: esse est percipi, which is clearly exemplary of Beckett's life-long scrutiny of human consciousness as well as of the eye's struggle with the I and vice versa. Having made various attempts to find a suitable interpreter for the puzzling role of the protagonist "O" (Charles Chaplin, Zero Mostel and Jack MacGowran proved to be unavailable), Beckett finally chose Buster Keaton, by then in his seventies, who accepted the part of "O," although the unforgettable icon of the silent-movie era had previously rejected the part of Lucky in the American Godot and his enthusiasm for a film in which mostly his back would be shown was somewhat modest.1

Beckett undertook his first (and last) journey to America in July 1964 where he collaborated with director Alan Schneider during the shooting of Film. In fact, this was the only time that Beckett wrote for the cinema screen. In 1965, Beckett's second visual project followed: his first television play, written in English and entitled Eh Joe which marked the beginning of his 'career' with the 'petit cran.' Most of his work for television, however, was carried out in the seventies and early eighties. These pieces were produced by the Sddeutscher Rundfunk in Stuttgart.

It is important to bear in mind that prior to Beckett's writing for television he had already expanded his artistic language while working for another electronic medium: radio. As all of his radio plays were written in the relatively short period between 1956 and 1962 it seems likely that in 1965 the timing was right for Beckett to further extend his creativity by writing for television. Moreover, Beckett had already incorporated another 'technical instrument,' such as the tape recorder in his stage play Krapp's Last Tape in 1958. With respect to Krapp it is most remarkable that Beckett wrote the play although he did not even own a tape recorder himself.2 Hence Beckett's integration of an electronic device into his play can be seen in the light of his larger artistic vision; Beckett had the ability to visualize how the recorder had to be used for the purposes of Krapp, there was no need for him to possess one in the first place.

The ability to think in visual terms is, of course, most important when writing for television. Although television is not a live experience, as is theatre, Beckett came to realize its distinct advantages: for example, his adaptation of the two stage plays What Where and Not I to the screen. Television allowed Beckett to focus on the interrogation as well as on the four heads of Bam, Bem, Bim and Bom, whereas in the stage play a lot of concentration seems to dissipate as the actors alternatingly come and go. In particular, the ending of the play, the simple announcement: "I switch off," is certainly more effectively communicated on television than on stage. As Tom Bishop has astutely commented: "'J'teins.' La encore, la pice fonctionne mieux a la television que sur scene. Bam s'teint littralement; la memoire s'arrete. Aucun clairage de scene ne reussit cette disparition." Similarly, the TV version of Not I in which the camera isolates the mouth in relentless close-up was better suited to capture the intensity of the uninterrupted flow of verbal spate than the theatre.

While this is not the place to discuss the possible advantages or disadvantages of television over theatre, I would like to briefly comment on two further aspects related to Beckett's use of television which, in my view, are essential to Beckett's artistic evolution. First, Beckett's work for and with the medium seems connected to his aesthetics of reduction or condensation, the principles of which he explained in his "German letter" to Axel Kaun: "To bore one hole after another in it [language], until what lurks behind it be it something or nothing begins to seep through...." Here, of course, Beckett's late prose comes to mind but also the above-mentioned refinement of What Where and his weariness of language during the process of making his television play Nacht und Traume in 1983. The quintessence of the aesthetics of reduction has been evoked by Martin Esslin: "Lorsque j'ai rencontr Beckett pour la premire fois, il y a vingt-cinq ans, il me dit, moiti par plaisantrie, qu'il s'efforcait de devenir de plus en plus concis, de plus en plus prcis dans sa faon d'crire:...peut-tre ne produirait-il enfin qu'une page blanche."5

The second aspect is linked to Beckett's revolutionary approach to television. Although other avant-garde artists such as the surrealists or Andy Warhol experimented with different domains, such as painting, filmmaking and writing, Beckett's treatment of television remains an unparalleled example in the history of the medium.6 While television represents, above all, a tool for mainstream entertainment and "escapism," Beckett's particular visual language, such as his self-reflexive treatment of the camera (whence his actual description of the camera as a "savage eye") converts this "wholly domesticated device," as Toby Zinman aptly calls television, into a marginal medium.7 For Beckett's images enveloped in "nuances of grey," whether they use language or are non-verbal, put our conscience as well as consciousness to the test. Beckett's pieces might be painful in that they invoke the loss of love, solitude or old age; yet most importantly they are indicative of the artist's scorn for complacent solutions and ready-made tales.

From this angle, then, Beckett undoubtedly, had the courage to use television as a responsible, and therefore emotionally intrusive, means of communication (in the literal sense of the word) between the artist or filmmaker and the viewer. Rather than quoting one of the favourite passages of many a Beckett scholar: "The expression that there is nothing to express, nothing from which to express...," it might be helpful to consider another equally powerful statement by Beckett on the Dutch painter Bram van Velde: "The much to express, the little to express, the ability to express much, the ability to express little, merge in the common anxiety to express as much as possible, or as truly as possible, or as finely as possible, to the best of one's ability" [my italics].8 As often, Beckett's remarks on other artists seem to reflect his own aesthetics: his commitment to his vision. This is elucidated by Alan Schneider's description of the efforts which his team undertook to make Beckett's vision happen:

Sometimes we glimpsed that vision clearly. Sometimes we fought it. Sometimes, many times, I'm afraid, we tried to achieve it and failed. Once or twice, we may have transmuted it into something it wasn't; perhaps, as in Sam's generous words afterward, acquiring 'a dimension and validity of its own that are worth far more than any merely efficient translation of intention.' But, in the process, it was exactly that faithful translation of intention we were all after.9

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Oeil Fauve»

Look at similar books to Oeil Fauve. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Oeil Fauve and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.