THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

Copyright 2011 by Andrea Wulf

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

Originally published in Great Britain by William Heinemann, an imprint of the Random House Group Ltd., London, in 2008.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

A portion of this work originally appeared in Early American Life magazine.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Wulf, Andrea.

Founding gardeners : the revolutionary generation, nature, and the shaping of the

American nation / Andrea Wulf.1st ed.

p. cm.

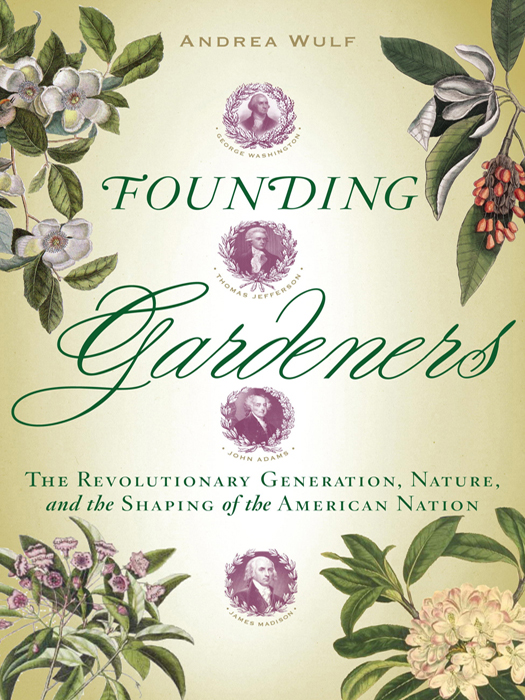

Summary: From the author of the acclaimed The Brother Gardeners, a fascinating look at the founding fathers from the unique and intimate perspective of their lives as gardeners, plantsmen, and farmers. For the founding fathers, gardening, agriculture, and botany were elemental passions, as deeply ingrained in their characters as their belief in liberty for the nation they were creating. Andrea Wulf reveals for the first time this aspect of the revolutionary generation. She describes how, even as British ships gathered off Staten Island, George Washington wrote his estate manager about the garden at Mount Vernon; how a tour of English gardens renewed Thomas Jeffersons and John Adamss faith in their fledgling nation; how a trip to the great botanist John Bartrams garden helped the delegates of the Constitutional Congress break their deadlock; and why James Madison is the forgotten father of American environmentalism. These and other stories reveal a guiding but previously overlooked ideology of the American Revolution. Founding Gardeners adds depth and nuance to our understanding of the American experiment, and provides us with a portrait of the founding fathers as theyve never before been seen.Provided by publisher.

eISBN: 978-0-307-59554-6

1. GardeningUnited StatesHistory18th century. 2. Gardens, AmericanHistory 18th century. 3. GardeningPolitical aspects. 4. Founding Fathers of the United States. 5. Political activistsUnited StatesBiography. 6. Conduct of life. 7. National characteristics, AmericanHistory. I. Title.

SB 451.3. W 85 2011

712.097309033dc22 2010052920

Jacket images: (clockwise, upper left, details) Steuartia by Mark Catesby, 1754, The New York Public Library / Art Resource, NY; Magnolia virginiana by Mark Catesby, 173143, Wellcome Library, London; Rhododendron maximum, 1806, Curtiss Botanical Magazine, Wellcome Library, London; Kalmia angustifolia by Mark Catesby, 173143, Wellcome Library, London; (center top to bottom) George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, James Madison, The Granger Collection, New York

Jacket design by Barbara de Wilde

v3.1

TO JULIA

And though the vegetable sleep will continue longer on some trees and plants than on others, and though some of them may not blossom for two or three years, all will be in leaf in the summer, except those which are rotten. What pace the political summer may keep with the natural, no human foresight can determine. It is, however, not difficult to perceive that the spring is begun.

T HOMAS P AINE , The Rights of Man

CONTENTS

1

The Cincinnatus of the West

George Washingtons American Garden at Mount Vernon

2

Gardens, peculiarly worth the attention of an American

Thomas Jeffersons and John Adamss English Garden Tour

3

A Nursery of American Statesmen

The Constitutional Convention in 1787 and a Garden Visit

4

Parties and Politicks

James Madisons and Thomas Jeffersons Tour of New England

5

Political Plants grow in the Shade

The Summer of 1796

6

City of Magnificent Intentions

The Creation of Washington, D.C., and the White House

7

Empire of Liberty

Jeffersons Western Expansion

8

Tho an old man, I am but a young gardener

Thomas Jefferson at Monticello

9

Balance of Nature

James Madison at Montpelier

AUTHORS NOTE

T HROUGHOUT the book I use the word garden in its broadest sense rather than in the narrow meaning of kitchen gardenit also includes lawns, groves and flowerbeds, as well as the larger cultivated ornamental landscape of an estate.

Similarly, I have also used gardener and gardening in an extended meaning. When the founding fathers are gardening, they might not actually be kneeling in the flowerbeds weeding, but they were involved in laying out their gardens, choosing plants (sometimes planting themselves) and directing their gardeners.

I N ORDER to avoid the unwieldy use in the text of both the common and Latin names of plants, I have used either one or the other, depending on the name by which a plant is most likely to be known. However, every plant is listed in the index under its common name (with the Latin name in parentheses) and under its Latin name (with its common name in parentheses).

PROLOGUE

M Y FIRST IMPRESSIONS of America were shaped when I went as a young woman on a seven-week road trip across the States, from Washington, D.C., to San Francisco. We drove hundreds of miles on roads that never curved, along a grid that mankind had imposed on nature. Some days we passed sprawling factories that were pumping out clouds of billowing smoke; other days we saw vast fields that seemed to go on forever. Everything differed in scale from Europe, even suburban America, where rows and rows of painted clapboard houses sit proudly on large open plots of immaculately shorn lawns. America exuded a confidence that seemed to be rooted in its power to harness nature to mans will and I thought of it as an industrial, larger-than-life country. I certainly never thought of it in terms of gardeningwhereas in Britain, everybody seems to be obsessed with their herbaceous borders and vegetable plots. In America, I believed, I was more likely to see someone driving a riding-mower than pruning roses.

T HEN, IN 2006, I went to visit Monticello, Thomas Jeffersons mountaintop home in Virginia, and began to understand how wrong I had been. On a sunny October morning, I stood on Jeffersons vegetable terrace, with straight lines of cabbages and squashes at my feet, and saw man and nature in perfect harmony. In the distance the horizon seemed to stretch into infinity; behind me was a manicured lawn lined with ribbons of flowers and, below, a romantic forest that crept into the gardens. The magnificent view from the terrace across the arboreal sea of autumnal reds and oranges of red maples, oaks, hickories and tulip poplars brought together Jeffersons neat plots of cultivated vegetables and sublime scenery of the Blue Ridge Mountains. Jefferson had combined beauty with utility, the untamed wilderness of the forest with the orderly lines of apples, pears and cherries in the orchard, and colorful native and exotic flowers with a sweeping panorama across Virginias spectacular landscape. If nature had been dominated by man, it seemed it was only in order to celebrate it.