GEORGE WASHINGTONS EYE

George Washingtons Eye

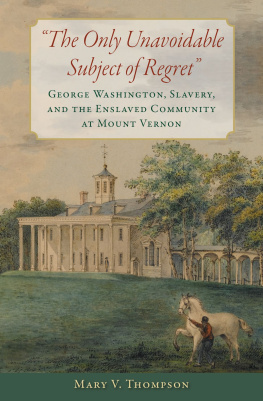

Landscape, Architecture, and Design at Mount Vernon

J OSEPH M ANCA

2012 The Johns Hopkins University Press

All rights reserved. Published 2012

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The Johns Hopkins University Press

2715 North Charles Street

Baltimore, Maryland 21218-4363

www.press.jhu.edu

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Manca, Joseph, 1956

George Washingtons eye : landscape, architecture, and design at

Mount Vernon / Joseph Manca.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4214-0432-5 (hdbk. : alk. paper)ISBN 978-1-4214

0561-2 (electronic)ISBN 1-4214-0432-X (hdbk. : alk. paper)ISBN

1-4214-0561-X (electronic)

1. Washington, George, 17321799Aesthetics. 2. Mount Vernon

(Va. : Estate) I. Washington, George, 17321799. II. Title.

III. Title: Landscape, architecture, and design at Mount Vernon.

NA737.W37M36 2012

711.409755291dc23 2011044973

A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library.

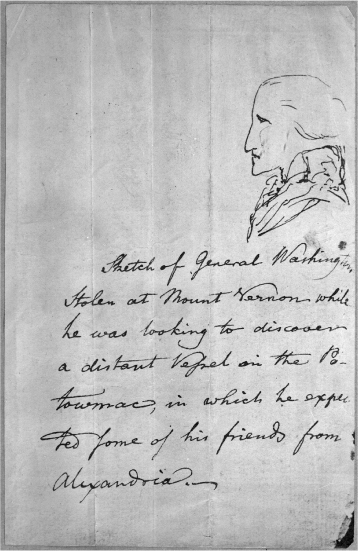

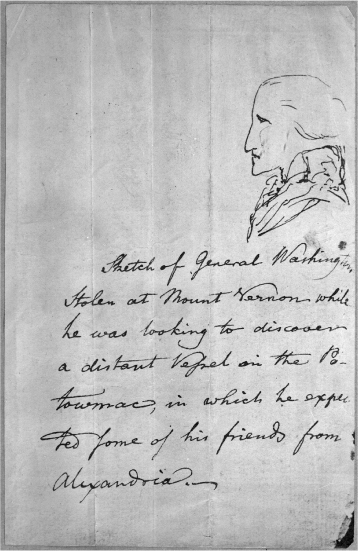

Frontispiece: Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Sketch of General Washington Stolen at Mount Vernon while he was looking to discover a distant Vessel in the Potowmac, in which he expected some of his friends from Alexandria, 1796, pen and ink on paper. Courtesy of The Maryland Historical Society (MS 523).

Special discounts are available for bulk purchases of this book. For more information, please contact Special Sales at 410-516-6936 or specialsales @press.jhu.edu.

The Johns Hopkins University Press uses environmentally friendly book materials, including recycled text paper that is composed of at least 30 percent post-consumer waste, whenever possible.

PREFACE

This is a book about George Washingtons eye for art and how he shaped the aesthetic world around him at Mount Vernon. He designed the expansions of his mansion house, provided plans for other buildings on his estate, and laid out and beautified elaborate gardens. He and Martha Washington filled their house at Mount Vernon with fine and decorative art. George Washington was keenly aware of the social and symbolic importance of his visual and material world, and although we are not concerned here in detail with Washington as military leader, legislator, agriculturalist, or president of the United States, his aesthetic activity occurred within the context of his life and historical era. Artistic issues for Washington were inextricably linked with moral and social concerns. The Mount Vernon estate was Washingtons public face, and his artistic decisions there must be seen against the backdrop of his personality, moral beliefs, and unique place in eighteenth-century American society.

George Washington was deeply interested in art, architecture, and landscape gardening, and I hope that this book shows the breadth and depth of Washingtons artistic creations and interests. He was a leading landscape gardener of his time and was the author of a fairly extensive architectural oeuvre. Washington stood in the forefront among American collectors of landscape art, and along the way he developed a good eye for style in paintings and prints. We need to reassess his place in early American intellectual life; the chapters that follow offer a glimpse into one part of his contributions to early American culture.

A study of George Washington is rewarding, as his life and art are well documented, and his aesthetic endeavors are in large part preserved and presented at Mount Vernon today. Washingtons actions were broadly consistent with those of other men of the social elite in eighteenth-century America, and at one level he serves as an example of an upper-class American patron: he built a large, stylish home, taking a leading role in determining its size and appearance; collected and displayed fine and decorative arts; developed beautiful gardens around his mansion house; and did it all with an awareness of his social position and how he would be perceived by others. But while there were other elite Americans and other wealthy Tidewater planters, there was only one George Washington, and his situation stands as a special case. He lived a large life and garnered an extraordinary amount of public attention, and he made a special effort to have his estate proclaim his own virtues and those of the new nation he helped to establish.

Washingtons artistic interests were varied, but one is struck by his extraordinary understanding of landscape, in the broadest sense. He apologized for his lack of knowledge of architecture, he was modest about his art collection, he feigned reluctance to sit for portraitists, he claimed no knowledge of poetry or music, and in his orders for furniture and other decorative arts he tended to rely on current or accepted taste. In the sphere of landscape gardening, though, he was lord and master. He worked for years at his designs, and he had the will, the knowledge, the land, the financial means, and the hired and enforced laborers to achieve what few others in America could accomplish. Lucky enough to have inherited an ideal site high on a broad river, he used this good fortune to advantage. The view of lawns, trees, and water that he created from the portico of his house is one of the great American works of art, a living canvas of space, color, and light. In the sphere of shaping nature he was unsurpassed in eighteenth-century America, and the theme of landscape runs throughout his life. He measured nature as a young surveyor and later shaped and adorned it, creating beautiful farms, setting his house to take perfect advantage of the prospects of forests and water, and carving vistas through the woods. He collected and displayed two-dimensional landscape art, had his house ornamented with stucco work of farm implements and flora, and wrote to others about the natural setting of his estate and his happy place in it. Like the theme of moral action and reputation, issues of landscape form a leitmotif throughout this book.

There is a large bibliography on Washington, much of it dealing with issues concerning the architecture of Mount Vernon and its gardens and collection, and I am deeply indebted to this previous scholarship. Robert Dalzell Jr. and Lee Baldwin Dalzells George Washingtons Mount Vernon and Allan Greenbergs George Washington, Architect provide in-depth information about Washingtons architectural designs. There have been several useful studies of the gardens, including Mac Griswolds Washingtons Gardens at Mount Vernon. Carol Borchert Cadous excellent recent volume, The George Washington Collection, discusses many fine examples of the art collection in Washingtons home, and Susan Detweilers George Washingtons Chinaware throws light on his acquisition and display of porcelain. A number of books and exhibitions, including works by Wendy Wick (George Washington, American Icon, with an introduction by Lillian Miller) and Hugh Howard (The Painters Chair), have explored the portraits of Washington and the vital role of his imagery in the context of Revolutionary and early national America. My task would have been difficult without one of the great scholarly projects of our time, namely, the ongoing publication of the George Washington Papers by the University of Virginia, a project that has online and searchable texts. Any scholar who works on George Washington stands on the shoulders of others and shares the company of many who have explored a complex person and his rich historical context.

Next page