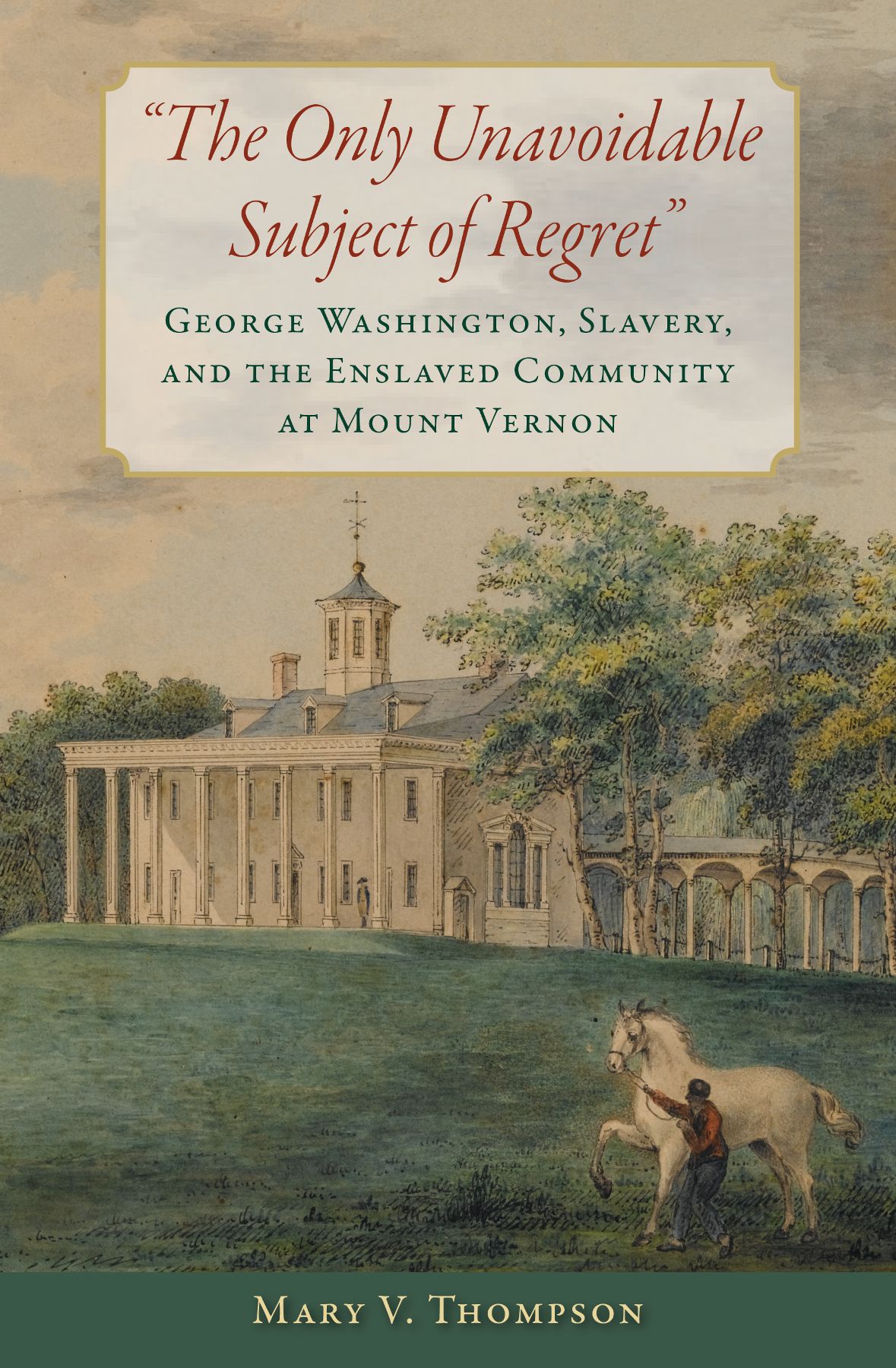

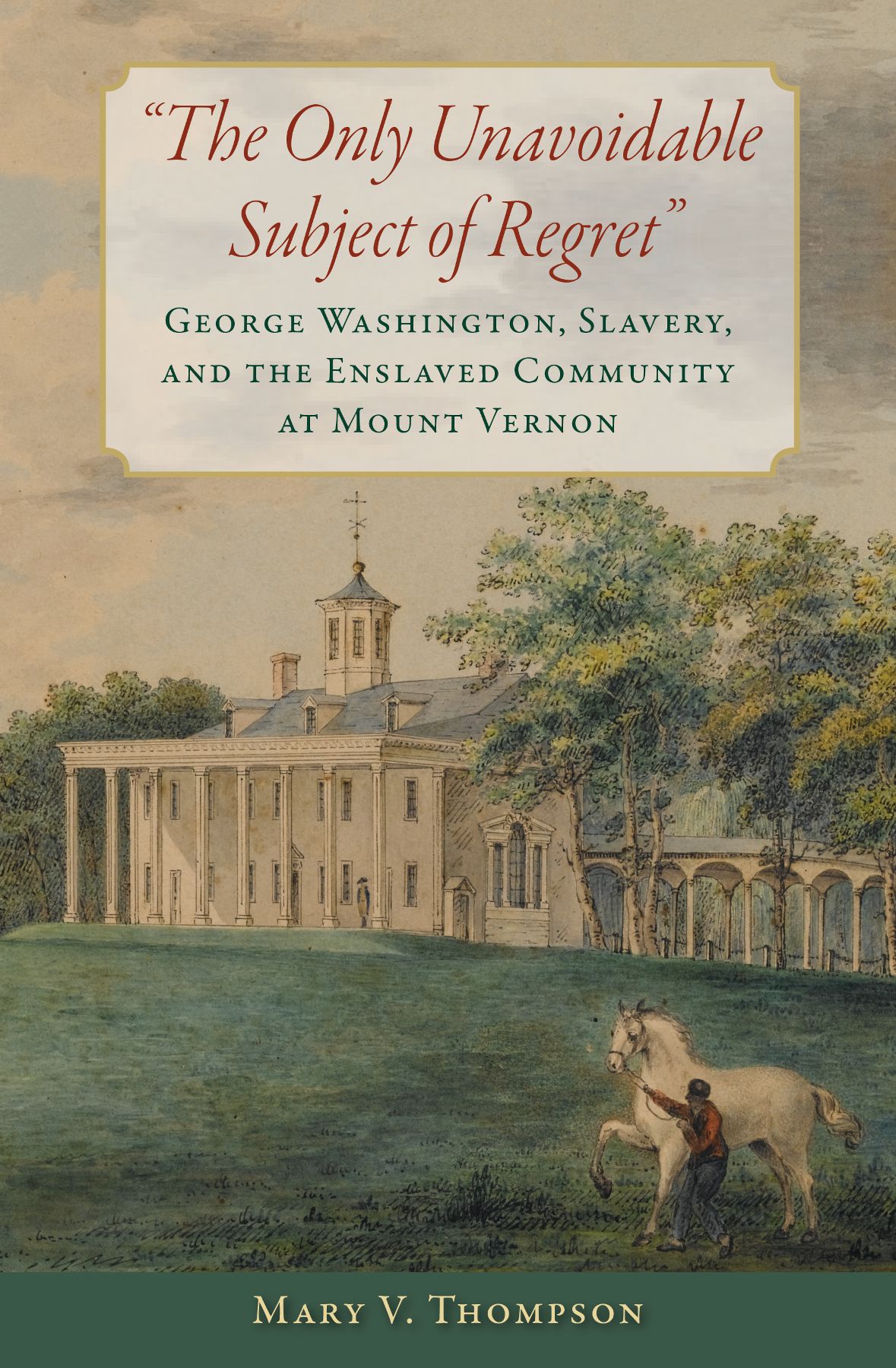

The Only Unavoidable Subject of Regret

The Only Unavoidable Subject of Regret

George Washington, Slavery, and the Enslaved Community at Mount Vernon

Mary V. Thompson

University of Virginia Press

Charlottesville and London

University of Virginia Press

2019 by the Rector and Visitors of the University of Virginia

All rights reserved

First published 2019

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Thompson, Mary V., 1955 author.

Title: The only unavoidable subject of regret: George Washington, slavery, and the enslaved community at Mount Vernon / Mary V. Thompson.

Description: Charlottesville : University of Virginia Press, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018046407 | ISBN 9780813941844 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780813941851 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH : Washington, George, 17321799Relations with slaves. | SlavesVirginiaMount Vernon (Estate)History18th century. | Mount Vernon (Va. : Estate)History18th century.

Classification: LCC E 312.17 . T 4665 2019 | DDC 973.4/1092dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018046407

Cover art: Potomak Front of Mount Vernon (detail), watercolor and ink over graphite, William Russell Birch, c. 18011803. (Courtesy of Mount Vernon Ladies Association)

For my husband, Anthony Marrs Bates, who has been with me through good days and many struggles, for almost as long as Ive been working on this project.

For Jane Brown (18891996), a dear neighbor and the daughter of a couple who had been enslaved. Thank you, Miss Jane, for teaching me that a person could live in slavery without being a slave in their heart. Your friendship, your positive spirit, and your ringing testimony of Gods love for you were inspirational. Im looking forward to sitting and talking with you again one day.

For the unknown and unexpected West African ancestor who provided 0.9 percent of my DNA. I so wish I could talk to you.

Contents

Figures

Tables (in Appendix)

In the formation of the United States, there have been a few processes that shapedand continue to shapethe way Americans see themselves. One of the best-known of these influences, for example, was the frontier, which contributed to the idea of American exceptionalism, that we were destined by God for great things, that we would not be limited by geography to a tiny sliver of land along the Atlantic Coast. It may also be responsible for the celebration of rugged individualism, leading, at its best, to the concept that each person has it within him- or herself to become anything that person wants, and, at its worst, to the belief that those who fail to succeed have only themselves to blame. The fact that we started out as colonies of several European countries may account for two paradoxical, but related, ideas: the inferiority complex many Americans feel in relation to the older and arguably more sophisticated cultures of our mother countries, and also the conviction that, having broken away from the most powerful of them by means of an almost assuredly doomed-from-the-start revolution, that we are better than they and have nothing to learn from those cultures.

Lastly, there is the fact that, for roughly 250 years, this country was built on the labor of unfree people, leading to a number of consequences that extend to this very day. According to some estimates, as many as 75 percent of all new arrivals in the British colonies were unfree, because they were working for a few years as indentured servants to pay back the cost of their travel to the New World, because they were convicts sentenced to labor for others in a foreign land, rather than face either a prison term at home or execution, or because they were enslaved for life. While the first two forms of unfree labor gradually faded, leaving few traces in our collective memory, slavery was something altogether different.

Slavery was nothing new in the world; as an institution it had existed for thousands of years and in many cultures, so it was not something invented in America. But in the Americasnot just the present-day United States but throughout North and South Americaslavery took a turn it had not in the rest of the world. Here it developed into a race-based institution, which for individuals held within its bonds was permanent and hereditary. Out of this system came views that people whose ancestors immigrated from Europe were naturally superior to people whose ancestors came from Africa; that black people were less capable, less intelligent, less cultured; and that expectations for them should be kept low. Those ideas meant that for generations after slaves were freed by means of a bloody civil war, they and their descendants were kept from voting, denied an education, segregated from those who considered themselves naturally better, more talented, more capable.

Slavery has been described as Americas original sin: the activity or state of mind that took America from the Edenic promise of its beginning, brought it to a debased and far lesser condition than it might have had, and continues to plague the nation today. For many years, this original sin was unacknowledged and, even today, because of the scars it left, can be difficult to discuss. But the Christian church has taught for two millennia that healing from sin can only come through acknowledgment of what happened, or confession, if you will. Psychology has essentially told us the same thing for the last century. And for those who are victims, rather than perpetrators, of sin, both religion and psychology prescribe understanding and forgiveness as the only way to move past the trauma and grow to ones fullest potential.

Learning the truth of what happened in the past is the first step in acknowledging the resulting social dysfunction and psychic scars that still plague us and allowing them to heal. Historians have been working very hard for roughly eight decades to ensure that the story of slavery in the Americas is told. Much of that work, however, was done at the university level and has only within the past thirty years or so begun to make its way from the academy to other institutions of learning such as museums. And it is only now that much of that story is making its way to a mass audience.

What that mass audience, in the form of the roughly 1 million visitors who come to Mount Vernon each year, often wants is an answer to the questions, Was George Washington a good slave owner? or He was good to his slaves, wasnt he? To anyone looking at this book to provide those answers, let me just say upfront that some of the worst things one thinks about in terms of slaverywhipping, keeping someone in shackles, tracking a person down with dogs, or selling people away from their familyall of those things happened either at Mount Vernon or on other plantations under Washingtons management. The story of this man and the enslaved people who lived at this site is complicated, but it is worth getting to know the real human beings involved, both the one who was our first president and those who knew him through the lens of Americas original sin.

This book is the result of many years of study undertaken as part of my job at Mount Vernon. My interest in the topic, however, began many years before. It was during my early years in elementary school that I first learned about slavery and the legacy of prejudice that still endured, as the nation commemorated the centennial of the war that abolished slavery in the United States, even as the civil rights movement played out each night on the evening news. My interest in history had early been fostered by my father, but it was in graduate school at the University of Virginia that I fell in love with African American history. There I started learning the academic story of slavery, partly through a seminar cotaught by Robert Cross and Steve Innes, and, most importantly, by a course called Slave Systems taught by Joseph Miller. The latter was probably the best class I have ever been privileged to take, and I will always be grateful to Mr. Miller (at Mr. Jeffersons University everyone, including professors, is addressed as Mr. or Ms., to maintain the ideal of democratic equality) for opening up this new world to me, as well as for the kindness and understanding he showed to all of his students. I came to work at Mount Vernon shortly before receiving my degree from the University of Virginia and immediately faced an interesting situation as no one spoke of slavesthey were servantsand I could see that roughly thirty-five to forty years of historiography were unacknowledged. Things would change at Mount Vernon in the ensuing years, and I am pleased that I have been here to see and be part of that transformation.

Next page