Thank you for downloading this 37 Ink/Atria eBook.

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from 37 Ink/Atria and Simon & Schuster.

C LICK H ERE T O S IGN U P

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

We hope you enjoyed reading this 37 Ink/Atria eBook.

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from 37 Ink/Atria and Simon & Schuster.

C LICK H ERE T O S IGN U P

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

Also by Erica Armstrong Dunbar

A Fragile Freedom: African American Women and Emancipation in the Antebellum City

An Imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright 2017 by Erica Armstrong Dunbar

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Atria Books Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

First 37 Ink/Atria Books hardcover edition February 2017

and colophons are trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

and colophons are trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at 1-866-506-1949 or .

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information, or to book an event, contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com.

Interior design by Amy Trombat

Jacket design by Eleen Cheung; Author Photograph by Whitney Thomas

Front Jacket images Stephen Mulcahey/Trevillion images (Apron); Collection of the New-York Historical Society, USA (Martha Washington); Gilbert Stuart (17551828) / Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts, USA / Bridgeman images ( George Washington, 17961803 (Oil On Canvas)); Shutterstock (Frame); Back Jacket image Granger, NYCAll Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN 978-1-5011-2639-0

ISBN 978-1-5011-2643-7 (ebook)

For my mother

Frances Chudnick Armstrong

&

My husband

Jeffrey Kim Dunbar

Contents

Authors Note

I MET ONA JUDGE STAINES in the archives about twenty years ago. I was busy conducting research on a different project about nineteenth-century black women in Philadelphia, and I came across an advertisement about a runaway slave in the Philadelphia Gazette . The fugitive in question was called Oney Judge, and she had escaped from the Presidents House. I was amazed. I wondered how could it be that I had never heard of this woman? What happened to her? Was George Washington able to reclaim her? I vowed to return to her story.

Those of us who research and write about early black womens history understand how very difficult it is to find our subjects in the archives. Enslavement,Judge Staines left the world just a bit of her voice, and, hopefully, time will reveal new information about this incredible woman. Although she remained in hiding for more than half a century, I dont believe that she ever wanted to be forgotten.

. I prefer to use the term enslaved when referring to men, women, and children who were held in bondage because it shifts the attention to an action that was involuntarily placed upon millions of black people. However, throughout the text, I chose to use the word slave for the purpose of narrative flow.

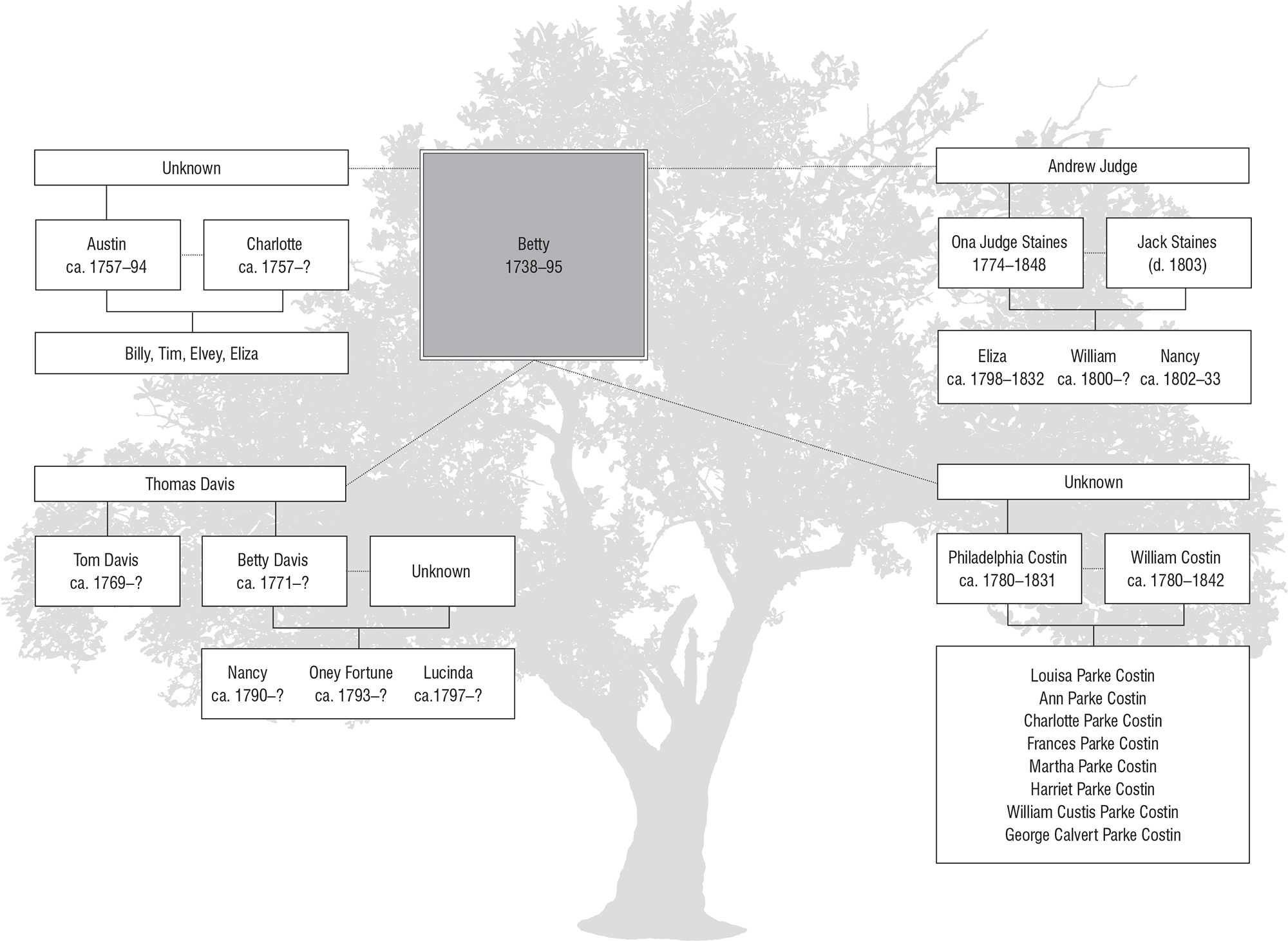

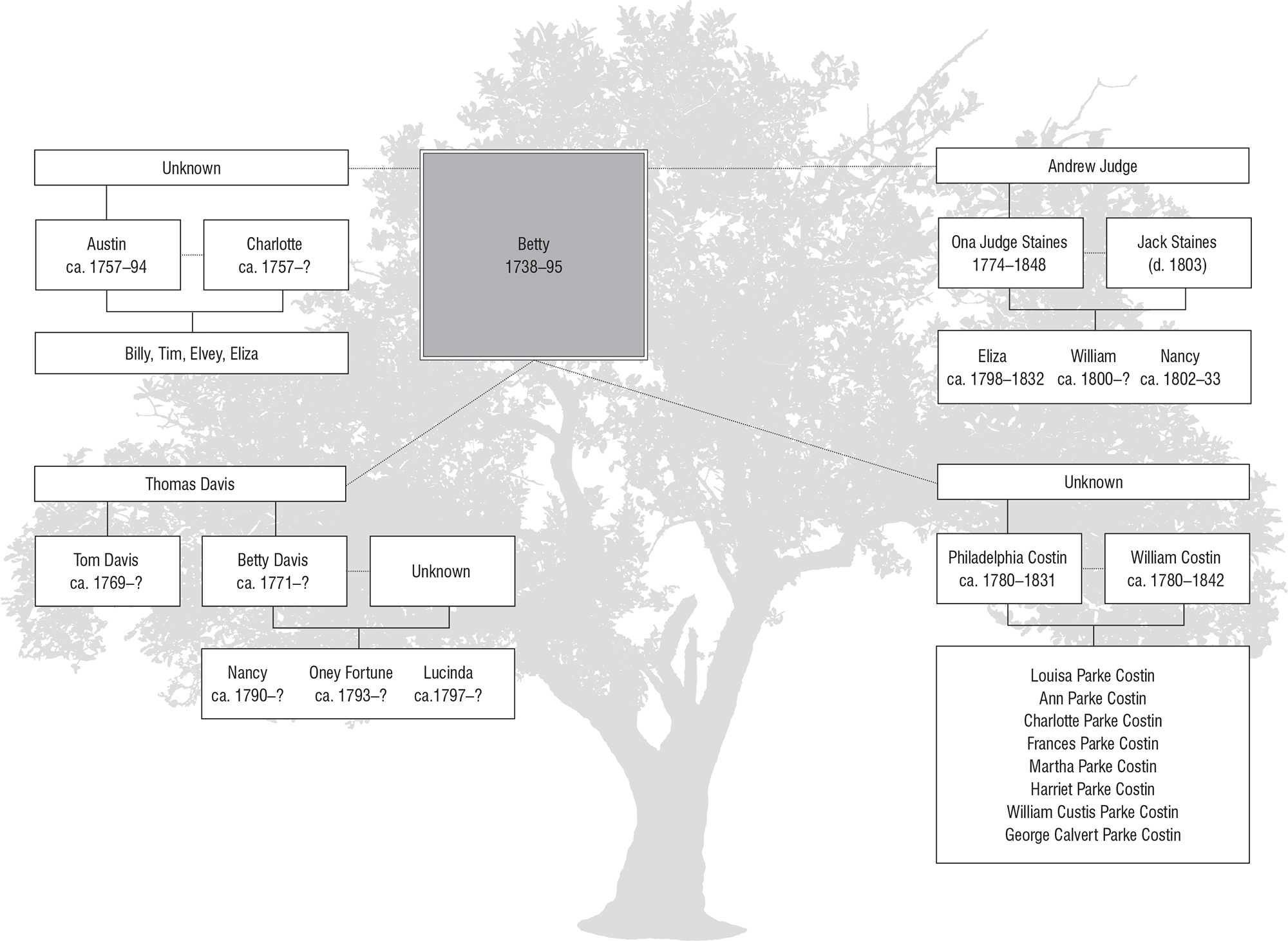

Onas Family Tree

This family tree shows the relationships, as far as they are known, between Ona Judges mother, Betty, and her children and their descendants.

Foreword

SPRING RAIN DRENCHED THE STREETS of Philadelphia in 1796. Weather in the City of Brotherly Love was often fickle this time of year, vacillating between extreme cold and oppressive heat. But rain was almost always appreciated in the nations capital. It erased the putrid smells of rotting food, animal waste, and filth that permeated the cobblestone roads of the new nation. It reminded Philadelphians that the long and punishing winter was behind them. It cleansed the streets and souls of Philadelphia, ushering in optimism, hope, and a feeling of rebirth.

In the midst of the promises of spring, Ona Judge, a young black slave woman, received devastating news: She was to leave Philadelphia, a city that had become her home. Judge was to travel back to her birthplace of Virginia and prepare to be bequeathed to her owners granddaughter.

Judge had watched six spring seasons come and go in Philadelphia. Each spring she watched the rain fall on a city that was slowly cleansing itself of the stain of slavery. She watched a burgeoning free black population grow such that by the end of the century, it would count nearly six thousand people. Although a slave, Judge lived among free people, watching black entrepreneurs sell, along with other provisions, their fruits, oysters, and pepper pot soup in the streets. On Sunday mornings she witnessed the newly erected Bethel church welcome its small but growing black membership. And what she didnt witness firsthand, she would have heard about. Stories about organizations such as the Pennsylvania Abolition Society, who helped enslaved men and women find or protect their freedom, and beyond. Philadelphia represented the epicenter of emancipation, allowing black men and women the opportunity to sample a few of the benefits that accompanied a free status.

As a slave in Philadelphia, Ona Judge was actually in the minority. In 1796 fewer than one hundred slaves lived within the city limits. Not only did her status as an enslaved person separate her from the majority of free black Philadelphians, but she was further distinguished by the family she served. Judge was owned by the first president of the United States and his wife, George and Martha Washington.

Judges sojourn from Mount Vernon in rural Virginia to the North began in 1789 when she accompanied the presidential family to New York, the site of the nations first capital. In November of 1790, the capital moved to Philadelphia, where Judge encountered a new world, one in which, on occasion, she strolled through the streets, visited the market, and attended the theater without her owners. The rigid laws of Southern slaveholding were difficult to integrate into a free Philadelphia, and when told shed be given away to the famously mercurial granddaughter of the first lady, she made a very dangerous and bold decision: she would run away from her owners. On Saturday, May 21, 1796, at the age of twenty-two, Ona Judge slipped out of the presidents mansion in Philadelphia, never to return.

Very few eighteenth-century slaves have shared their stories about the institution and experience of slavery. The violence required to feed the system of human bondage often made enslaved men and women want to forget their pasts, not recollect them. For fugitives, like Ona Judge, secrecy was a necessity. Enslaved men and women on the run often kept their pasts hidden, even from the people they loved the most: their spouses and children. Sometimes, the nightmare of human bondage, the murder, rape, dismemberment, and constant degradation, was simply too terrible to speak of. But it was the threat of capture and re-enslavement that kept closed the mouths of those who managed to beat the odds and successfully escape. Afraid of being returned to her owners, Judge lived a shadowy life that was isolated and clandestine. For almost fifty years, the fugitive slave woman kept to herself, building a family and a new life upon the quicksand of her legal enslavement. She lived most of her time as a fugitive in Greenland, New Hampshire, a tiny community just outside the city of Portsmouth.

Next page

and colophons are trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

and colophons are trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.