Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2014 by Bob Arnebeck

All rights reserved

First published 2014

e-book edition 2014

ISBN 978.1.62585.258.8

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014953171

print edition ISBN 978.1.62619.721.3

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

To Leslies vegetables

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Most of the research for this book was done at the National Archives, Library of Congress and Historical Society of Pennsylvania in the late 1980s for my book Through a Fiery Trial: Building Washington 17901800. After publication of that general history of the citys founding, which hardly told the story of the slaves and other workers, I still could not keep my hands off those records that told more about what the masons, carpenters, bricklayers, quarriers and slave laborers did. I kept sharing insights from the records on my web pages, and historians like John G. Sharp and Terry Buckalew shared their ongoing work on the Washington Navy Yard and a recently discovered African American graveyard in Philadelphia. Buckalew is uncovering the life of Ignatius Beck, one of the slaves who worked on the Capitol. We all keep the faith that, with patient work, we could focus light on forgotten lives. The work that genealogists have put online has also been invaluable, especially those exploring Charles County, Maryland. Edward Papenfuse has made the Maryland Archives online into a gold mine for anyone looking for nuggets of early history. James Gage, at StoneStructures.org, helped me identify quarry tools. Julia King shared insights on George Hadfields views on slavery.

Banks Smither of The History Press rescued me from the web and resuscitated an interest in making a book with illustrations. Finding illustrations was not easy. Artists in the 1790s were not inclined to depict working men. Today, museums and historical societies are overly protective of portraits in their collection, so I couldnt fill the book up with men wearing wigs. To capture some idea of what workers in the 1790s experienced, I had to widen my search. Fortunately, I was not alone. I received help from my wife, Leslie Kuter; James Gage at StoneStructures.org; Jerry McCoy at the Georgetown Public Library; Dawn Bonner at the Mount Vernon Ladies Association; Chris Hodapp, who knows all about Freemasonry; Sara Good at the Mercer Museum in Doylestown, Pennsylvania; and fellow devotee of Washington history Don Hawkins, whom I literally met in the primordial swamp.

Leslie also read chapters and sent me snarling back to make needed revisions. Our son, Ottoleo, saved the day by looking things up in the library. Marlee shared her potato chips and liked what she read. Finally, thanks to airlines never refunding fares despite book deadlines, I learned that there is no better place to research the stones of Washington than in Italy, Switzerland and Austria. Luca, Sarah, Sergio, Victoria and Gaby stimulated the brain as well as the palate. And what should I see in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna but Bruegels Tower of Babel with the perfect and timeless detail depicting a laborer attending a mason.

INTRODUCTION

In 1798, a Polish tourist, Julian Niemcewicz, inspected the work on the Capitol. All who saw the large building under construction were impressed, and Niemcewicz was no exception. But his eyewitness account of the construction is exceptional in one respect: only he noticed the hired slaves working on the building. He spent two days walking around the Capitol and jotted down his impressions in his diary. He marveled at the huge scaffolding surrounding the building and 200 workers, raising the stones by means of machines and placing the first framework of the roof. He asked to see the architect and was led up to the roof. He didnt describe the workers but noticed that all were working in silence. Walking around the building, he saw that for a considerable distance the ground was covered with huge blocks ofstone, some already cut and polished, others yet undressed. There were sheds for working and a shelter for the workers, plus some cabins scattered here and there and a few grogshops.

When he came to the site for a second look, he got a different impression. At eleven oclock in the morning, no one was at work: they had gone to drink grog. He learned that the workers took two grog breaks a day as well as a break for breakfast and dinner. All that makes four or five hours of relaxation. One could not work more comfortably. Then he corrected himself. There were men working on the building. The negroes alone work.

In the eighteenth century, Negro was synonymous with slave. He didnt estimate how many slaves he saw working, only saying he saw them in large number. At first he was impressed. Someone told him that the slaves earned eight to ten dollars a week. But he soon learned the truth: I am told that they were not working for themselves; their masters hire them out and retain all the money for themselves. What humanity! What a country of liberty. If at least they shared the earnings! And in 1798, those earnings happened to be a little over six dollars a month.

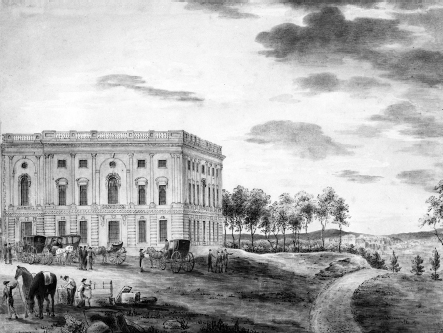

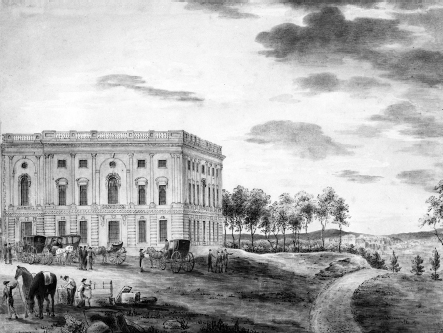

Thomas Birchs drawing of the Capitol in 1800. Only the North Wing was completed. From the Library of Congress.

Julian Niemcewicz was the only tourist to write down his impressions of the hired slave laborers. 1822 portrait by Antoni Brodowski. From Wikimedia Commons.

Unfortunately, Niemcewicz told us nothing more about the slaves. He didnt even speculate as to why the slaves who got no pay kept working while the other men, who were paid by the day and not by the hour, loafed. He didnt mention seeing slave overseers with whips.

Like most European tourists who came to the city, he soon moved on to Mount Vernon, where the recently retired president presided over his plantation with over three hundred slaves. The relations between the races were more clear-cut there. The slaves did all the farm and housework while the whites lived graciously. Niemcewicz inspected the fieldwork and slave quarters, which he thought rather shabby. He enjoyed the Washingtons hospitality.

Eyewitness accounts are usually the stuff of history. Niemcewiczs report on Mount Vernon is one of the best we have. In 1798, it was easier for a tourist to focus on the ordered world of plantations like Mount Vernon than on the chaotic arrangement on and around Capitol Hill. Not only were stones strewn about the Capitol but around the hill, houses, the building blocks of a city, seemed strewn about in a haphazard fashion. Niemcewicz described the city as he viewed it from the unfinished roof of the Capitol: The great avenues cut into the forest of verdant oak, indicated the spaces destined for streets, but todayone sees nothing and hears there only the silence of the trees.

Next page