2007 by Bruce Chadwick

Cover and internal design 2007 by Sourcebooks, Inc.

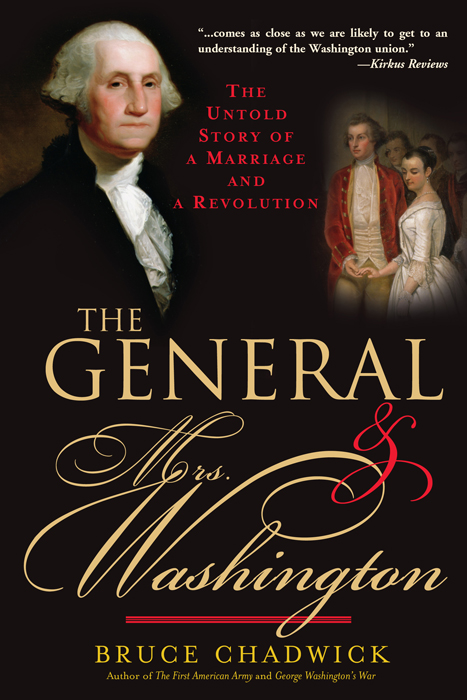

Portrait of George Washington (1732-99) after a painting by Gilbert Stuart (1755-1828) (oil on canvas) by Durand, Asher Brown (1796-1886)

Collection of the New-York Historical Society/Bridgeman Art Library

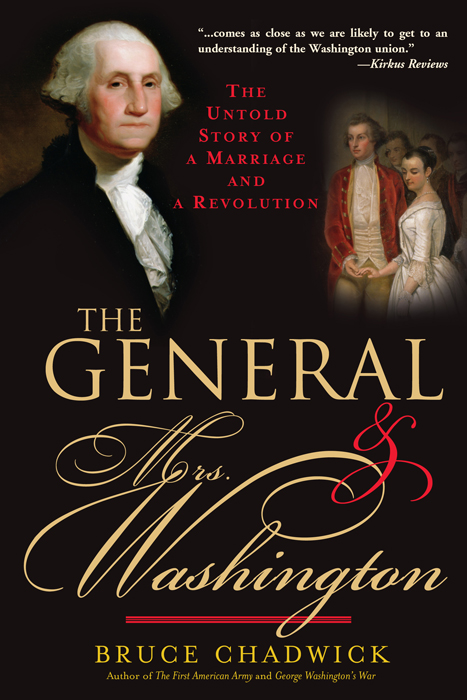

The Marriage of Washington (1732-99) 1849 (oil on canvas) by Stearns, Junius Brutus (1810-85)

Butler Institute of American Art, Youngstown/Bridgeman Art Library Museum Purchase 1966

Internal photos used by permission as noted in captions

Sourcebooks and the colophon are registered trademarks of Sourcebooks, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systemsexcept in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviewswithout permission in writing from its publisher, Sourcebooks, Inc.

Published by Sourcebooks, Inc.

P.O. Box 4410, Naperville, Illinois 60567-4410

(630) 961-3900

Fax: (630) 961-2168

www.sourcebooks.com

Originally published in hardcover by Sourcebooks, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Chadwick, Bruce.

The general and Mrs. Washington : the untold story of a marriage and a revolution / Bruce Chadwick.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. Washington, George, 1732-1799--Marriage. 2. Washington, Martha,

1731-1802--Marriage. 3. Married people--United States--Biography. 4.

Generals--United States--Biography. 5. Generals' spouses--United

States--Biography. 6. United States--History--Revolution, 1775-1783.

I. Title.

E312.19.C47 2006

973.4'10922--dc22

[B]

AUTHOR TO READER

Just before she died in 1802, Martha Washington burned the hundreds of letters that she had exchanged with her husband George during the Revolutionary War. No one knew why. Were the letters too private? Was George, so careful in his public statements, overly critical of others in that correspondence? Well never know. The destruction of those private letters, which must have revealed much about the Washingtons personal relationship, was a great loss to historians and to the country. The letters surely would have provided a more complete look at the way the mind of George Washington worked during the Revolution and, just as important, his concerns for his wife and family.

Washington, as the commander in chief of the Continental Army and later as the first president of the United States, wrote thousands of letters during his life and kept most of them. Just about all have been published somewhere. The letters, in war and peace, helped historians to construct a comprehensive portrait of him.

Martha did not write many letters. However, a lengthy study of the letters written by her and to her, and about her by others, enabled me to write a rather full description of the first First Lady. (The term did not come about until 1849. Martha was called the Presidents Lady, or Lady Washington, but I use First Lady because Americans are so familiar with it.) These descriptions of her, and assessments of her inner strength and mercurial personality, came from farflung sourcesimportant figures such as Thomas Jefferson, Abigail Adams, and an assortment of public officials, newspaper editors, and foreign diplomats. But they were also jotted down by unknown peoplemen who rode past her on roads, little girls who rode in carriages with her, merchants, farmers, and the many soldiers who met her during the Revolution.

Using all of these sources, I tried to write a biography of the Washingtons that not only established their place in history but also captured their personalities and the deep love they had for each other. I tried to explain, too, what at first seemed unfathomablethe extraordinary love of the American people for the countrys First Couple. That is rather easy in Georges case because he was the conquering war hero. Understanding the respect for his wife, who led no charges and fired no guns, was much harder. In the end, though, I think I did so by explaining the brand-new Americans of the Revolutionary era. Americans were then, and remain today, a people who admire men and women of great character and integrity, men and women who risk all for freedom.

Such a couple was George and Martha Washington.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

One would think that writing a biography about the most famous man in United States history and his wife would not be a difficult task. After all, every schoolchild knows their story. The problem I had was not telling the story that everybody knew, but the story that people did not know.

To do so, I had to write about the Washingtons within the context of the extremely complicated and, at times, stormy era in which they lived. How did George Washington go from being a bungling field commander to the most famous man in the world in just two weeks, following the crossing of the Delaware River on Christmas 1776, on his way to stunning victories at Trenton and then Princeton? If women were invisible and powerless in the eighteenth century and lived only for the men in their lives, how did a rather ordinary-looking woman such as Martha Washington become so cherished by men as well as women throughout the land?

The answers lay in the political, economic, social, and cultural changes taking place in the United States at the same time that the struggling colonies were attempting to defeat the British Empire in what eventually became the most successful revolution in the history of the world. It is that cultural landscape that I address throughout the book, hopefully painting a picture of the entire country and its people that will enable the reader to see how the Washingtons fit into that portrait and, in fact, became the centerpiece of it.

I had the help of many kind people along the way. First and foremost was Mary Thompson, the historian of Mount Vernon, Washingtons magnificent estate in Virginia on the banks of the Potomac. The cherubic Ms. Thompson, one of the nations finest scholars in her own right and the author of a work on Martha Washington, was kind enough to read through the manuscript and offer many constructive suggestions.

Librarians everywhere helped me in my research, cheerfully handing me yet ten more books to read, twenty more journals to dissect, and one more stack of original letters to go through. Most helpful were the librarians at New Jersey City University, Rutgers University, Washington and Lee University, the Morris County (N.J.) Library, Randolph (N.J.) Library, New York Public Library, the Valley Forge and Morristown National Historical Parks, and those at the historical societies of Massachusetts, New York, Connecticut, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Virginia, and Maryland.

I had assistance from photo experts at the New York Historical Society and Dawn Bonner at Mount Vernon, plus Scott Houting at Valley Forge National Historical Park, Johnni Rowe at the Morristown National Historical Park Andrea, Ashby-Leraris at Independence National Historical Park in Philadelphia, and Christine Jochem and Suzanne Gulick at the Morristown-Morris Township Library.

Special thanks go to Jo Bruno and Liza Fiol-Matta at New Jersey City University for giving me travel grants to complete work on this project.

I would like to thank Hillel Black, the executive editor of Sourcebooks, who urged me to write about George and Martha and did a wonderful job editing the manuscript. This is my third book about the Revolutionary era for Sourcebooks in what has been a happy relationship. Thanks, too, to Michelle Schoob, Heather Moore, Tara VanTimmeren, Alison Syring, Megan Dempster, Scott R. Miller, and Libby Topel at Sourcebooks.

Next page