W hen General George Washington successfully led the American Revolution against the most powerful military force in the world, that of the British Empire, King George III reportedly said that if Washington laid down his sword after his stunning, startling, and world-altering victory, he would be regarded as the greatest man in the world.

That is precisely what Washington did.

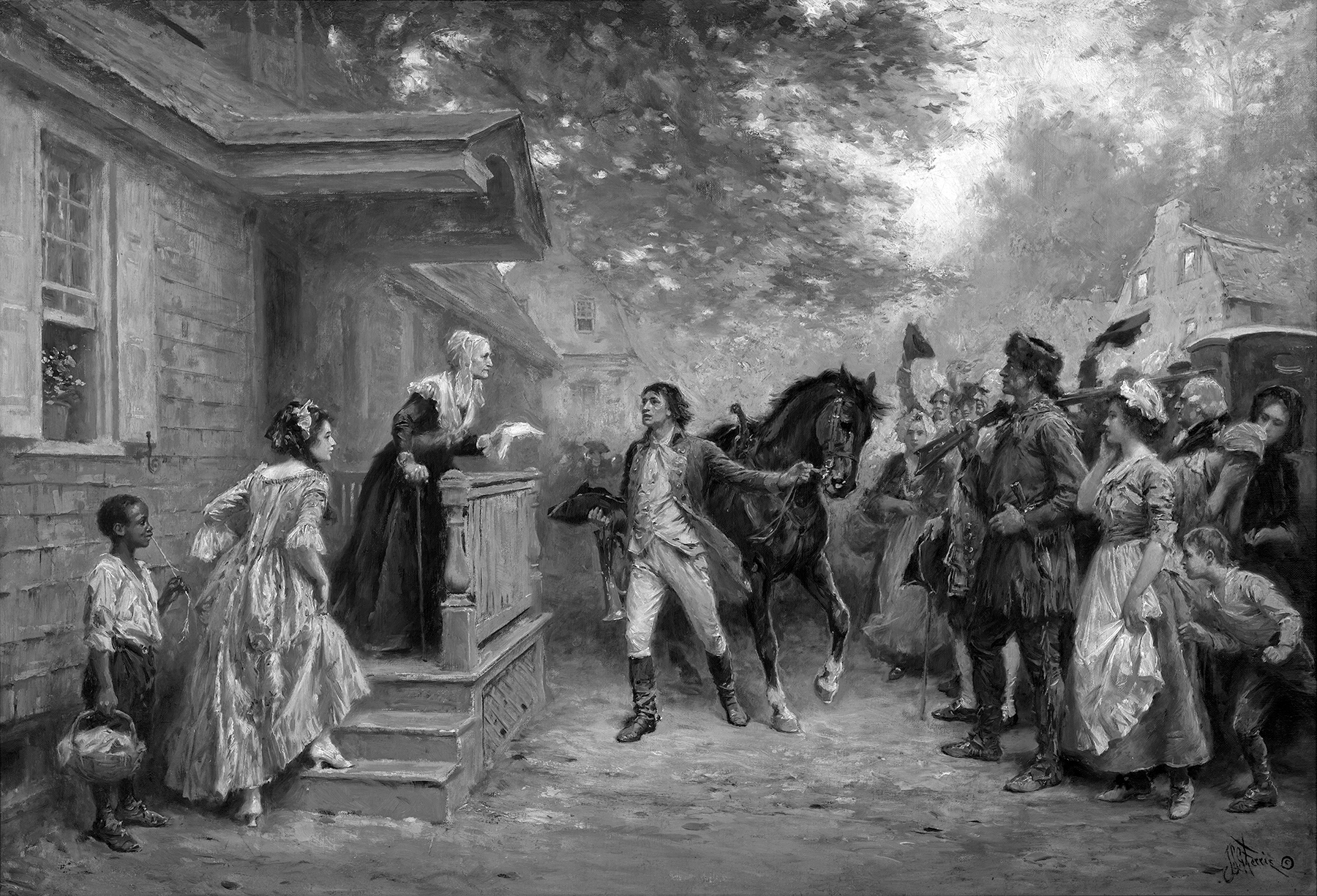

At the conclusion of the Revolutionary War, he went before the Continental Congress in Annapolis, Maryland, on December 23, 1783, laid down his weapon, and made a brief speech. After celebrations and after commemorations, he left and went home to become, again, Planter Washington.

He was eager to return to his beloved wife, Martha, and his cherished Mount Vernonwhich he hadnt been to in seven years, except briefly to entertain some French officers while on his way to Yorktown and a date with destiny against General Charles Cornwallisto get back to the life of the gentleman farmer he so loved. In character, he gave the credit for the miracle of the American Revolution to others.

Your excellency is retired like [another] Cincinnatus, wrote the Marquis de Chastellux at the close of the Revolutionary War. Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus, about 2,250 years earlier, having won against the fierce Aequians as a Roman general, refused absolute power and instead went back to his farm and his plow. One of Washingtons generals, the redoubtable and later secretary of war Henry Knox, formed the Society of the Cincinnati in 1783, comprising Washingtons commanders in the field from the Revolution and their descendants. The Society exists today and has a national office in Washington, D.C.

WASHINGTON DID NOT JUST ARRIVE WITHOUT CAUSE AT HIS EXALTED STATUS , beloved by his fellow countrymen for over two hundred years, with children, citiesincluding Washington, D.C., in 1791monuments, mountains, schools, even states and holidays named in his honor. And later, as the standard by which all future presidents would be measured, recorded as also the greatest president by most historiansa man who would be widely revered for his integrity, grace, manners, charm, Christian faith, and humility. His devout mother played a key role in the development of his character. While he was sometimes described as having little genuine affection for Mary, the reserved Washington still credited her with his principled and moral upbringing. Indeed, this was inevitable, for when George was eleven, his father died, leaving Mary Washington a single mother.

The relationship with his own mother was laden with difficulty for both of them. Self-centered and acquisitive, Mary Ball Washington was preoccupied with her eldest son to the virtual exclusion of her other [four] children. That preoccupation expressed itself in fears for Georges safety, pleas not to put himself at risk in military action, and demands for assistance, usually monetary, even though she continued to occupy and enjoy the profits of his property on the Rappahannock, said Patricia Brady in Martha Washington: An American Life.

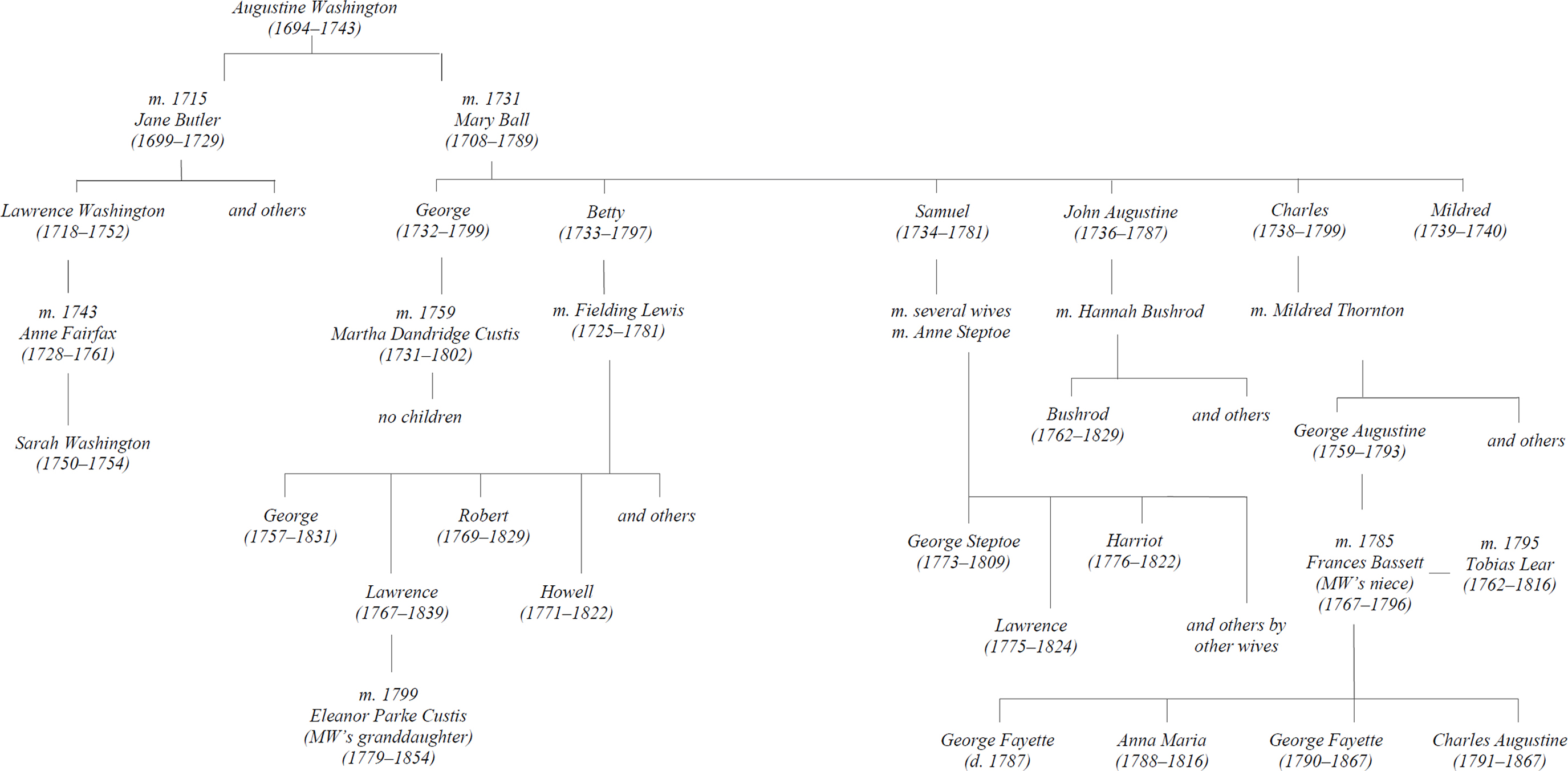

HIS FATHER, AUGUSTINE (GUS), HAD A NOBLE APPEARANCE AND MANLY proportions. George was just eleven years old. Augustines will was shortly probated and he left his son George the plantation of Ferry Farm, an equal division of slaves and estate, and a lot in the newly formed and nearby town of Fredericksburg. Mary was to supervise the children until they came of age.

Georges fourteen-years-older half brother, Lawrence, went off to fight in the amusingly named War of Jenkins Ear in 1740, leaving George consumed by his loneliness. When Lawrence returned, to the admiration and hero worship of his younger half brother, he settled fifty miles north from the family, away at a plantation named Epsewasson, high above the Potomac River. Lawrence later renamed it Mount Vernon, after the famed British admiral Edward Vernon, whom he deeply admired.

Mary Washington, ne Ball, Augustines second wife, lived at Ferry Farm and raised George, tutoring him, admonishing him, driving him to distraction often, loving him, and also fashioning the boy who would eventually become one of the greatest men in history. One historian wrote of young Georges and his mothers strength of wills as incompatible, but this, said Dorothy Twohig, fostered young Washingtons independence and self-reliance. Later, control of Ferry Farm, which Augustine had left George, became a source of irritation between the son and his mother.

MARY WAS BORN AROUND 1708 OR SOTHE EXACT DATE IS NOT KNOWN. (Many ages in this book are approximated.) Much of her life was a mystery, sometimes placing her in some historical studies as less of a person and more of a mythic figure. Her family, the Balls, were prominent in the Millenbeck and Epping Forest parts of Virginias Northern Neck, jutting out into the Chesapeake Bay, adjoining the Potomac on one side and the Rappahannock River on the other.

Though she was well provided for by her husband, it was tough going for Mary Ball Washington after Augustines passing. She was a widow in her late thirties, raising six children all by herself, supervising farms, supervising slaves, supervising her family. She never remarried, though she would have been an attractive catch, at a still desirable age and very wealthy. But it was well known around Fredericksburg, Virginia, that she was a handful and at times frustrating. Her son, by contrast, was equally legendary for his reserve.

However, his resolute reserve in adulthood had not always been so. In his youth, George Washington had a fearsome temper. This was observed not just by his mother, but by people such as Thomas, Lord Fairfax, in a note to Mary: I wish I could say that he governs his temper.... He is subject to attacks of anger on provocation, sometimes without just cause. Perhaps he learned something from his mother.

Georges capacity for rebellion may have been prompted by Marys overprotective care. His later language describing the Revolution evokes a mother and son. The Mother Country, George wrote, thought it was only to hold up the rod, and all would be hush!