Little joy has he who has no garden, said Saadi. Montaigne took much pains to be made a citizen of Rome; and our people are vain, when abroad, of having the freedom of foreign cities presented to them in a gold box. I much prefer to have the freedom of a garden presented me. When I go into a good garden, I think, if it were mine, I should never go out of it. It requires some geometry in the head, to lay it out rightly, and there are many who can enjoy, to one that can create it.

THE POLITICS AND PASSIONS OF GARDENS

To see anothers garden may give us a keen perception of the richness or poverty of his personality, of his experiences and associations in life, and of his spiritual qualities.

CHARLES DOWNING LAY , A Garden Book, 1924

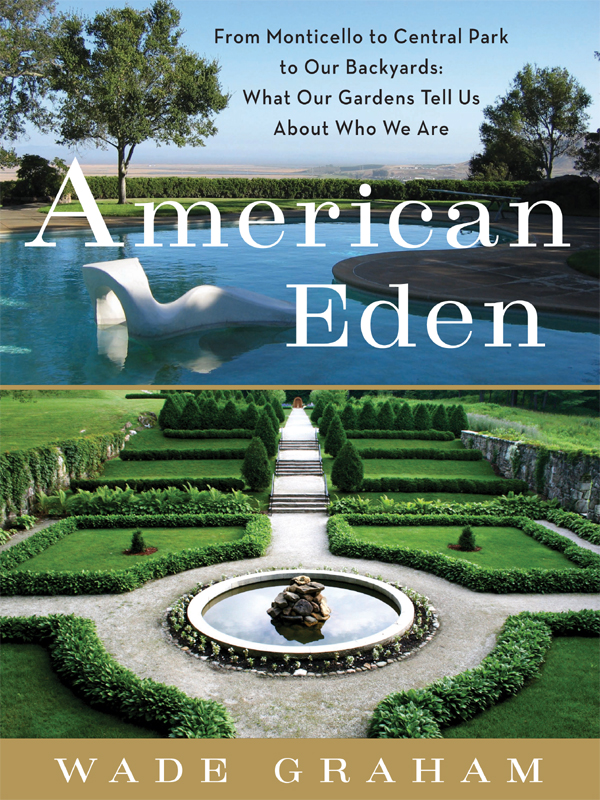

T his book is a history of gardens in America, from the colonial and revolutionary periods to the present. It is about the form, feel, and life of gardens and the lives of the people who make them, but also about much more. It starts from my conviction that our gardens are meaningfulthat they say a lot, and that we can read in them stories, not only about their makers but about ourselves as a people our people , in Emersons words: we Americans. It is informed by the several sides of my work: designing gardens, all over the country, for all kinds of people and all manner of situations; and studying and writing about Americas cultural and environmental history.

Though born of agriculture, gardens are not farms. One definition from 1839 serves reasonably well: a garden is landlaid out as a pleasure groundwith a view to recreation and enjoyment, more than profit. Its function is essentially social: a garden is in effect a miniature Utopia, a diorama of how its makers see themselves and the world. Anyone who creates a garden draws a map of their mind on the ground, whether consciously or not. If we take time to read them, carefully situating them in the matrix of architecture, art, literature, and social and economic circumstances in which they are embedded, gardens may tell us about the wealth, power, status, sex lives, ethnicity, religion, politics, passions, aspirations, delusions, illusions, and dreams of their creators. Always rooted in their time and place, even the most unique gardens are indicators and traces of the tensions and energies in a constantly changing society. They can express political theories, aesthetic preoccupations, scientific and religious ideas, cultural inheritances, and sheer force of personality. Thomas Jeffersons layered landscape at Monticello in Virginia expressed all of these things and more, providing us with a map, not only of his deep engagement with the ideas and values of the Enlightenment, but of his own, often deeply conflicted mind as a statesman, businessman, slave owner, farmer, and lover. All his life he worked to reconcile his democratic ideals with his love of luxury and the trappings of aristocracy, and his vision of an egalitarian, agrarian society with the harsh realities of the economic system that underpinned his own statusplantation slavery. Inspired by new British styles in gardens as well as by new ideas about rights, government, and society coming from Great Britain, yet wanting no more to do with that mother country, he struggled to adapt them to the new nation that he contributed so much to conceiving. His garden, every bit as much as his celebrated writings, is a testament to this seminal work of creating something unprecedented: an American character, and an American landscape to go along with it.

Jeffersons dilemmas are still with us: we love to ogle the ostentatious houses and gardens of come-lately billionaires; at the same time we take pride in Michelle Obamas kitchen garden at the White House, planted by schoolchildren with two hundred dollars worth of supplies. As a people, and as individuals, we want to express our values and virtues, and our sense of responsibility to community and the natural environment, while allowing space for our dreams and aspirations to flower, and, for some of us, our wealth. We must reconcile life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, as the founder described them in the Declaration of Independence. Like Jefferson, we look abroad, to Europe, Asia, or elsewhere for models and inspiration, and we seek to transform those borrowed styles into a distinctively American form. For some of us the preferred expression in the garden is no-holds-barred ostentation in imitation of European royalty, like George Washington Vanderbilts Biltmore Estate; for some it is a Grandmothers humble cottage garden of flowers and vegetables; for most, though, it is an amalgam, a middle ground, that weaves the different, competing strands of our heritage into a cultural fabric that is generally middle-class but keeps one eye faithfully on an agricultural past and one, perhaps hopefully, on the dream of one day making it big. Just as Jeffersons house and garden drove him deeply into debt as he built and rebuilt them obsessively until the end of his life, chasing the evolving image of perfection he held in his minds eye, our gardens reveal the economic volatility and dynamism that have fueled American social mobility, and attendant anxieties about class and status, from the beginning. In every age, old money and new, established social groups and ascendant ones, try to negotiate their shared spaces in part through questions of taste, style, display, and the narratives that are spun around them. What was true in Jeffersons time was true in the Gilded Age at the end of the 19th century and remains true in our era of Hamptons hedge fund billionaires and reality TV makeover shows. Martha Stewart has nothing on our Founding Gardener.

The musician Jack Johnson sings, Ive got a symbol in my driveway, as a comment on how we use things like cars to speak for us, often assigning them certain lines in the play that we write about ourselves that we are hesitant to utter in our own voices. The drama of self-creation isnt straightforward, but full of deviations, diversions, dodges, and impersonations. What makes gardens especially interesting (versus, say, buying cars, houses, clothes, art, companies, or sports teams to show the world who we are) is that making one constitutes the creation of a new worldour own world, often nearly from scratch, an Eden where outside stresses, failures, and compromises cant enter (at least in theory).

The comparison to drama isnt far-fetched: since ancient times gardens have been compared to stages and used as settings for plays, masked balls, and myriad entertainments; sibling arts, stage and garden are each dramatizations of life and lives. Like theater, our gardens also tell of deeper, personal stirrings: of romantic love, of nostalgia for lost times and places, certainties, dreams, securities, and especially for childhood, that place of refuge, real or imagined. American gardens frequently evoke Arcadian agrarian landscapes, expressing our yearnings for the supposedly simpler lives of a rural time past, even as we have inexorably become an urban people living in an industrialized world churned by war, economic and social upheaval, and the displacement of communities in the face of the constant movement our system voraciously feeds on.

Emerson liked to quote Saadi, the 12th century Persian traveler-poet who chronicled the people and gardens he met on his peregrinations through the Middle East, Central Asia, and India. The gardens Saadi wrote about descended from ancient Persia: the paradeiza , or walled kings hunting grounds, which passed into Greek as paradeisos , which was the model for the biblical Garden of Eden in the book of Genesis. Like ancient desert cities, gardens were walled to keep out the bad and shelter the good, in all senses. This is why, as Emerson said, one longed for the freedom of a garden: the keys, permission to enter the bounded refuge of a space apartseparate from other peoples lives, separate from the tumult of the city and the vicissitudes of nature alike, since a garden isnt nature but rather an entwining of nature and culture in a highly promiscuous, productive pas de deux.