Contents

Guide

Australia

HarperCollins Publishers Australia Pty. Ltd.

Level 13, 201 Elizabeth Street

Sydney, NSW 2000, Australia

www.harpercollins.com.au

Canada

HarperCollins Canada

2 Bloor Street East - 20th Floor

Toronto, ON M4W 1A8, Canada

www.harpercollins.ca

New Zealand

HarperCollins Publishers New Zealand

Unit D1, 63 Apollo Drive

Rosedale 0632

Auckland, New Zealand

www.harpercollins.co.nz

United Kingdom

HarperCollins Publishers Ltd.

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF, UK

www.harpercollins.co.uk

United States

HarperCollins Publishers Inc.

195 Broadway

New York, NY 10007

www.harpercollins.com

American Eden: From Monticello to Central Park to Our Backyards: What Our Gardens Tell Us About Who We Are

DREAM CITIES. Copyright 2016 by Wade Graham. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

FIRST EDITION

ISBN: 978-0-06-219631-6

EPub Edition January 2016 ISBN 9780062196330

16 17 18 19 20 OV/RRD 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

In order to go forward and consider the city that might be, we must look at the many visions of our cities since the beginning of the massive urbanization that marks this century. What have the proposals been? Have they been tested, and if so, what have we learned from them? What were the values that guided their authors, and to what extent has society itself changed in the unfolding of the saga of twentieth-century urbanism?

MOSHE SAFDIE, 1997

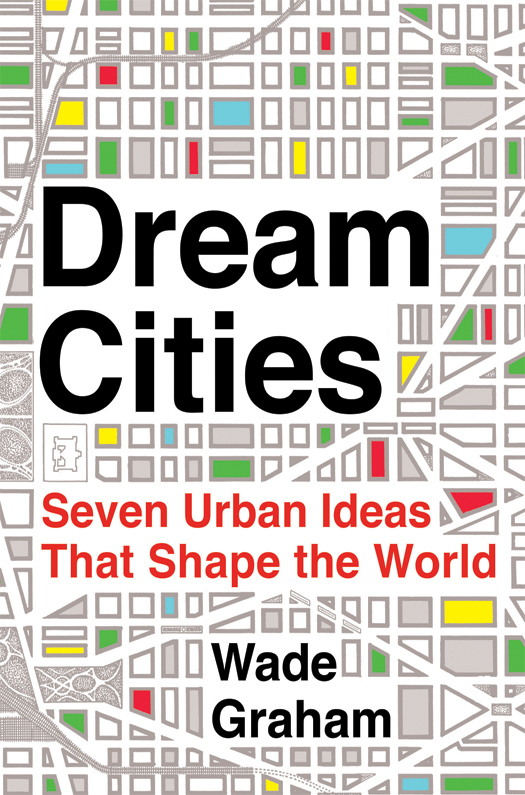

D ream Cities is a book that explores our cities in a new wayas expressions of ideas, often conflicting, about how we should live, work, play, make, buy, and believe. It tells the stories of the real architects and thinkers whose dreamed-of cities became the blueprints for the world we actually live in. From the nineteenth century to today, what began as visionary conceptssometimes utopian, sometimes outlandish, always controversialwere gradually adopted and constructed on a massive scale, becoming our concrete reality, in cities around the world, from Dubai to Shanghai to London to Los Angeles. Through the lives of these pivotal dreamers and campaigners and those of the acolytes and antagonists who translated or fought their plans, we can trace the careers not just of the urban forms that surround usthe houses, towers, civic centers, condominiums, shopping malls, boulevards, highways, and spaces in betweenbut also of the ideas that inspired them, embodied in buildings, neighborhoods, and entire cities. Dream Cities aims to show how to see the world we already inhabit in a new way, to see where our urban formsour architecturescome from, how they intend to shape us, how we shape them in turn, and how we participate in the whole process.

Conventional histories of architecture talk about style, and the uniqueness of buildings as though they are art objects, like paintings, independent of their context. But cities are all context, made up not simply of buildings but of assemblies of forms and the spaces and relationships between them, and between this built environment and us. These architectures are what make cities real: each is a design, intention, assertion, thrust, or counterthrust in the long-running battles and debates about how we ought to live. Dream Cities is a history of where these forms came from and how they work, and a field guide for identifying and decoding them.

Sometimes we build cities all at once, like new towns, suburbs, or capitals right from the drawing board. Mostly, they are built over time, by different parties, with various bits superimposed on or pushing into one another, displacing, erasing, destroying, replacing, and being replaced. This is why so many cities feel disjointed and complexthey can be read as layers recording change over time as traces, stacks, and collisions, or like partial graveyards of old architectures, many that still live on, being added to, abandoned, or repurposed. Cities can also be read as battlegrounds where different architectures compete, each with an agenda, and economic and political consequences. There are winners and losers. The program of one kind of urban form is often incompatible with other values embodied in other kinds of form. Some use more resources than others, or take resources from another. Some divide and alienate us from other people, from the shared life of communities, or from responsibility for the planet. Always, when a dream architecture becomes a reality, there are unintended consequences.

The glass towers of downtown business districts stand against traditional neighborhoods with their mix of residences, commercial buildings, and community spaces; the leafy streets of affluent gated enclaves seem to deny the concrete cell blocks built to house the masses in so much of the world, cut off from the rest of the city by elevated highways; pseudo-rural, car-dominated, suburban sprawl competes with the density and inclusiveness of pedestrian-scaled neighborhoods, whether in traditional older city centers or in recent mixed-use developments; huge, hyper-designed experience shopping malls and ground-up mini-cities built around retail replace Main Street mom-and-pop stores and redefine the boundaries of public and private space in our lives.

Architectures are expressions of the desires of their designers and builders; these forms intend to shape people and thus shape the world. As churches intend to make people pious, prisons to make them obedient, schools to make them attentive, or monuments to make them civic-minded, we build our cities with intent, each type of built form designed to produce a given outcome, provide a particular environment, promote or discourage a certain behavior. Dream Cities is concerned with the new architectures of the modern world, as envisioned by their most influential dreamers. Tall towers and fast highways intend to make us feel and act modern and efficient; monumental museum districts, parks, avenues, and plazas to make us feel orderly and civic; shopping malls to make us want to buy, and in doing so to make us happier; sprawling suburbia to make us feel independent and free of the city and its crowding, and when historically themed, to make us forget our present reality by transporting us to other time realms; eco-friendly developments to make us feel in enlightened balance with nature.

It would seem logical that urban forms should reflect the enormous differences in climate and geography where people live. The Inuit igloo, the Puebloan cliff dwelling, and the white masonry villages of the Mediterranean are marvelous adaptations to their surroundings. Topography, geology, winds, temperatures, and weather all played a part in how traditional cities were built. But these days, local variation is hard to spot. In the modern era (since about 1850 in Western Europe and America and now everywhere), cities look more alike than they do different, from Singapore to Ulan Bator to Boston to Moscow to Buenos Aires. Aside from those parts of them built before the modern erathe odd churches, squares, and low-rise historic districtsthere is a remarkable, global urban monotony: here are tower blocks, there freeways, there shopping malls, over there pseudo-historic suburbs, here a formally ordered civic center, beyond that, mile after mile of car-dependent sprawl. These elements make up the major part of most modern cities, and yet they are rarely mentioned in tourist guides or architectural histories, or even acknowledged.