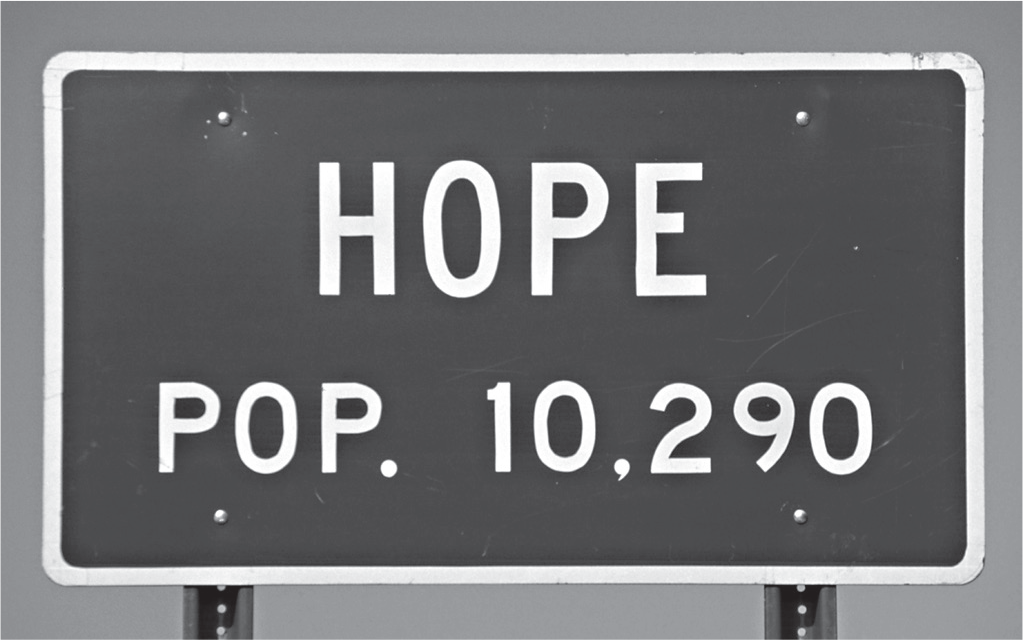

With a population small enough to fit comfortably into the bottom third of a New York skyscraper, Hope, Arkansas, is a city in name only. It still managed to become the birthplace of a US president, Bill Clinton.

Deyan Sudjic

THE LANGUAGE OF CITIES

PENGUIN BOOKS

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

First published by Allen Lane 2016

Published in Penguin Books 2017

Copyright Deyan Sudjic, 2016

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Cover images Getty Images/DK Images/Wikimedia Commons

ISBN: 978-0-241-18805-7

City is a word used to describe almost anything. A tiny settlement in the mid-West, with fewer than 10,000 people, and nothing more than a sheriff to represent civic authority, is called a city. So is Tokyo, with a population approaching 40 million, an urban structure based on multiple electoral districts, a parliamentary chamber, a governor, a prefectural government employing 250,000 people and a multi-billion dollar budget.

If anywhere can be defined as a city, then the definition runs the risk of meaning nothing. A city is made by its people, within the bounds of the possibilities that it can offer them: it has a distinctive identity that makes it much more than an agglomeration of buildings. Climate, topography and architecture are part of what creates that distinctiveness, as are its origins. Cities based on trade have qualities different from those that were called into being by manufacturing. Some cities are built by autocrats, others have been shaped by religion. Some cities have their origins in military strategy or statecraft.

These are not generic elements that always produce the same outcomes. Many cities have a river; but the Seine is unique and an essential part of what makes Paris different from Berlin and the Spree. Hong Kong is a trading city, so are Dubai and Hamburg, but they are unmistakably themselves. Not all the characteristics of distinctiveness are positive. The ruined hulk of a beaux arts theatre that is now used as a car park is a very specific part of the identity of only one city, Detroit.

In material terms, a city can be defined by how close together its people gather to live and work, by its system of government, by its transport infrastructure and by the functioning of its sewers. And, not least, by its economic potential. One definition of a city is that it is a wealth-creating machine that can, at the minimum, make the poor not quite as poor as they were. A real city offers its citizens the freedom to be what they want to be. The idea of what makes a city is more elusive, but is as significant as the data. Just a short walk from the scars left in the fabric of New York by the destruction of the Twin Towers, the words of two American poets have been spelled out in heavy block capitals cast, letter by letter, in bronze into a sequence of railings next to the Hudson. They lack precision, and fail to offer prescriptions for urbanism, yet they have resonances missing in more materialistic definitions of a city.

Walt Whitmans tone is that of a soaring eulogy:

City of the sea!

City of wharves and stores! city of tall faades of marble and iron!

Proud and passionate city! mettlesome, mad, extravagant city!

Whitmans first two lines, which would mean little to the 45th president of the United States, are missing. They reflect an even more important measure of urbanity:

City of the world! (for all races are here;

All the lands of the earth make contributions here)

And then, a little further along the waterfront, with the litter of new high-rises lining the New Jersey shore visible across the river, Frank OHara is more laconic:

One need never leave the confines of New York to get all the greenery one wishes I cant even enjoy a blade of grass unless I know theres a subway handy, or a record store or some other sign that people do not totally regret life.

The verses are the product of an unusually enlightened piece of place-making under the lugubrious shadow of what used to be called the World Financial Center, which paid for it. The Iranian-born artist Siah Armajani selected the verses and designed their physical setting to create somewhere for office workers to feel the sun, and smell the tang of the Hudson in the air.

Whether the World Financial Center itself, formed of six distinct buildings totalling eight million square feet, lives up to Whitmans idea of a city is an open question. The development summed up the essence of a certain approach to city-making, at a particular moment in the evolution of New York. That this approach, replicated all around the world, is no longer current is demonstrated in the renaming of the site. The World Financial Center survived 9/11, but is called Brookfield Place now. Deloitte, Fidelity and the Wall Street Journal are based at 200 Liberty Street, a tower which, in the way favoured by developers when it was built in the 1980s, used to be called One World Financial Center, just as Merrill Lynch is at 250 Vesey Street, once known as Four World Financial Center.

The new addresses are a gesture towards Jane Jacobs, the greatest critic of big-picture planning. They reflect a belated realization that monster-size blocks disrupt street patterns. But simply giving a million square feet of office space in a 40-floor tower a street address is not going to turn it into a piece of an intimate, pedestrian-scaled city. Brookfield Place is still an urban monoculture, created on landfill. It offers a civilized enough place in which to eat a sandwich lunch, it has an ice rink and an events programme to encourage shoppers at weekends. At Christmas the Winter Garden is lit up every night.

Brookfield Place is owned by the same development company that controls Canary Wharf in London, which has a no less ambitious public art programme, and a similar abundance of places to eat. Like Brookfield Place, Canary Wharf accommodates the local outposts of global companies from American Express to Nomura. They cluster together, in all but interchangeable surroundings, like the present-day version of the kontor compounds the word means counting house or office established by the Hanseatic League in the fifteenth century. Hansa traders spread out across northern Europe, from the free cities of the Baltic, setting up enclaves as far away as the Steelyard in London. They kept themselves to themselves and took their architecture with them everywhere they went, much in the manner of twenty-first-century investment bankers using their American decorators to construct cinemas, swimming pools and wine cellars beneath their terraced houses in Holland Park.

Walt Whitman spent his later life in Camden, New Jersey, which suggests that while he appreciated the qualities of a great metropolitan city, he himself did not feel the need to spend his time in one. Frank OHara, on the other hand, lived a life on East 9th Street that could only have been possible in what we understand to be a city in the modern sense. It was the life of a gay man in the New York of the 1950s, a city which demonstrated the limits of its liberalism by becoming the first jurisdiction in the United States not to legalize homosexuality, but to define it as a misdemeanour rather than a felony.