Copyright 2018 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College

All rights reserved

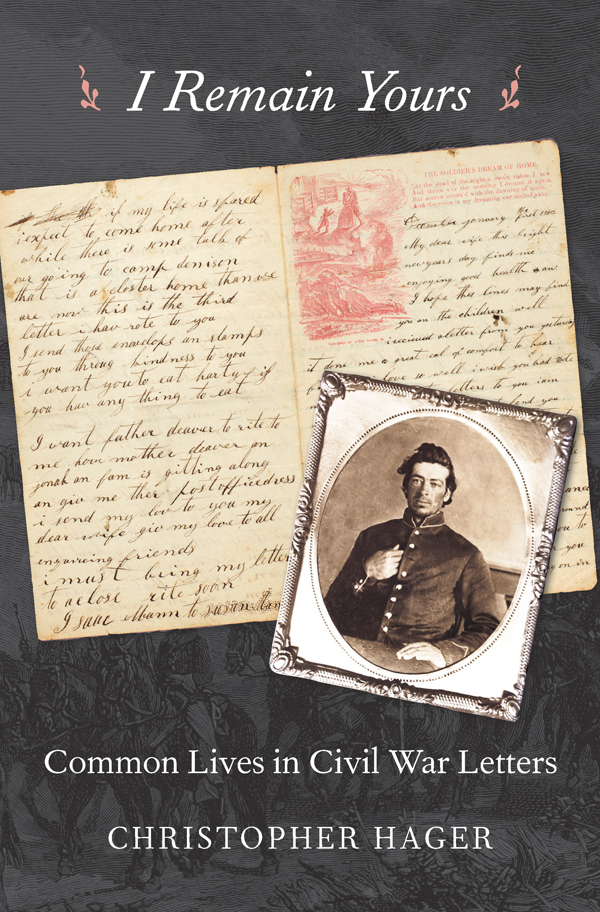

Jacket art: Background: The Rear-Guard, engraving after Alfred Rudolph Waud (18281891), Private Collection /

Bridgeman Images. Letter: Letters from Isaac Mann to Susan Deaver Mann, 18621864, Isaac Mann Civil War letters (HM 2188221908), Huntington Library, San Marino, CA. Portrait: Courtesy of Daryl Lovell.

Jacket design: Annamarie McMahon Why

978-0-674-73764-8 (cloth)

978-0-674-98181-2 (EPUB)

978-0-674-98182-9 (MOBI)

978-0-674-98180-5 (PDF)

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Names: Hager, Christopher, 1974 author.

Title: I remain yours : common lives in Civil War letters / Christopher Hager.

Description: Cambridge, Massachusetts : Harvard University Press, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017015477

Subjects: LCSH: United StatesHistoryCivil War, 18611865Sources. | Letter writingUnited StatesHistory. | SoldiersUnited StatesCorrespondence. | Working classUnited StatesHistoryCorrespondence. | United StatesHistoryCivil War, 18611865Personal narratives.

Classification: LCC E468 .H22 2018 | DDC 973.7/8dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017015477

O N SEPTEMBER 23, 1990, the first episode of Ken Burnss documentary The Civil War aired on PBS. It concluded with a letter written in 1861 by Sullivan Ballou, an army officer from Rhode Island, to his wife, Sarah. As many soldiers did on the eve of battle, Ballou had a premonition that this letter might be his last: O Sarah, if the dead can come back to this earth, and flit unseen around those they loved, I shall always be near youin the garish day, and the darkest nightamidst your happiest scenes and gloomiest hoursalways, always; and, if the soft breeze fans your cheek, it shall be my breath; or the cool air cools your throbbing temples, it shall be my spirit passing by. Sarah, do not mourn me dead; think I am gone, and wait for me, for we shall meet again. While the actor Paul Roebling read these words, viewers saw photograph after photograph of uniformed men standing with their wives and children. After the letter had been read, the films narrator said, Sullivan Ballou was killed a week later at the First Battle of Bull Run, and the screen went blank.

I was a high-school student at the timetoo young to understand the letters depth of feeling, appreciate conflicts of conviction, or sympathize with a husbands longing for his wife. I certainly was old enough, though, to notice that my father, sitting across the living room in his usual chair, was crying. There probably has never been another moment, leaving aside news coverage of assassinations and catastrophes, when as many Americans simultaneously wept. There certainly has been no other instant in which so many were so moved by the words of a single letter as when nearly forty million people sat before their televisions and listened to the words of Sullivan Ballou. The next day, public television stations were flooded with requests for copies of the letter. Ken Burns later called it the most beautiful letter Ive ever read, and its beauty has earned it a place as the most famous and best appreciated Civil War letter.

Sullivan Ballou was exceptional. Educated at Andover and Brown, a well-to-do attorney who entered the Union army as a major, he was a likely candidate to write a graceful and memorable letter. He had practice. Since the dawn of English settlement in North America, men of Ballous station in life had been accustomed to writing letters on a nearly daily basis, for reasons both personal and professional. But Ballous eloquence gave him no monopoly on the will to communicate feelings of longing and devotion. Larkin Kendrick, a twenty-four-year-old farmer, born and raised where the North Carolina Piedmont rises toward the Blue Ridge Mountains, was serving in the Confederate army during the first year of the war when he wrote these words to his wife, Mary Catherine:

I often think of you and my beloved little children I of ten maid the wonder when the son was a setting behin the western Horising if it was a shedding its brite Rays on my lovely home I often look at the moon and the countless stares and wonder if my belove ones is a behold the same seen my Dear companion I never Shal forgit you for my love to is as costant as the Wheales of time the tim is a huring us on to a neve ending eturnty I hope if we never meat on earth we may meat where the Sound of the Drum and war whoop is heard no moar.

Sullivan Ballous education and gentility can be credited only for his spelling, not the lyrical and emotional reach of his words. That comes from some other place, to which poor farmers like Larkin Kendrick had equal access.

THE FIRST MODERN history of Civil War literature, Edmund Wilsons Patriotic Gore (1962), began with the sour declaration that the period of the American Civil War was not one in which belles lettres flourished. Other scholars of his era concurredone called it an unwritten warand even Walt Whitman, who lived through it, predicted that the real war will never get in the books. Today a flourishing field of academic study demonstrates just how rich and deep Civil War literary culture was, and it has become customary to remember Wilsons book for its note of disapproval. He went on to say, though, that the Civil War did produce a remarkable literature which mostly consists of speeches and pamphlets, private letters and diaries, personal memoirs and journalistic reports. Has there ever been a historical event, Wilson marveled, in which so many people were so articulate?

He did not mean Larkin Kendrick. Although Patriotic Gore is devoted to a literature of the everyday more than to belles lettres, it still revolves around the work of published authors, wealthy diarists, generals, and statesmennot poor farmers who had never gone to school. It may seem difficult to muddle through Kendricks poor spelling and see him as articulate, but this book is devoted precisely to letters like histo a Civil War literature authored by ordinary Americans who used letters to hold their families together during a time of great trial.

Part of what makes the Civil War such a remarkable moment in American history is indeed that so many people were so articulate. The personal letters that millions of Civil War soldiers and their families wrote to each other between 1861 and 1865 number somewhere close to half a billion. Although it is impossible to be precise, all available estimates point to the same order of magnitude. A Northern relief worker recorded the volume of mail into and out of Union army camps as averaging 180,000 letters per day. Multiplied out for four years of war, that translates into well over 250 millionfor the North alone. A New York chaplain tallied 3,855 letters he mailed for his regiment in the single month of April 1863. If his regiment was typical, it suggests soldiers in the Army of the Potomac alone, about one-sixth of federal forces, produced a million outbound letters per month. There is no reliable way to calculate the number of letters soldiers received from civilians, but it would be nearly as large. Any reasonable calculation yields a figure of several hundred million, in a country that had a population slightly over thirty million people and a literacy rate, though among the highest in the world at the time, markedly lower than it is today.