Contents

Guide

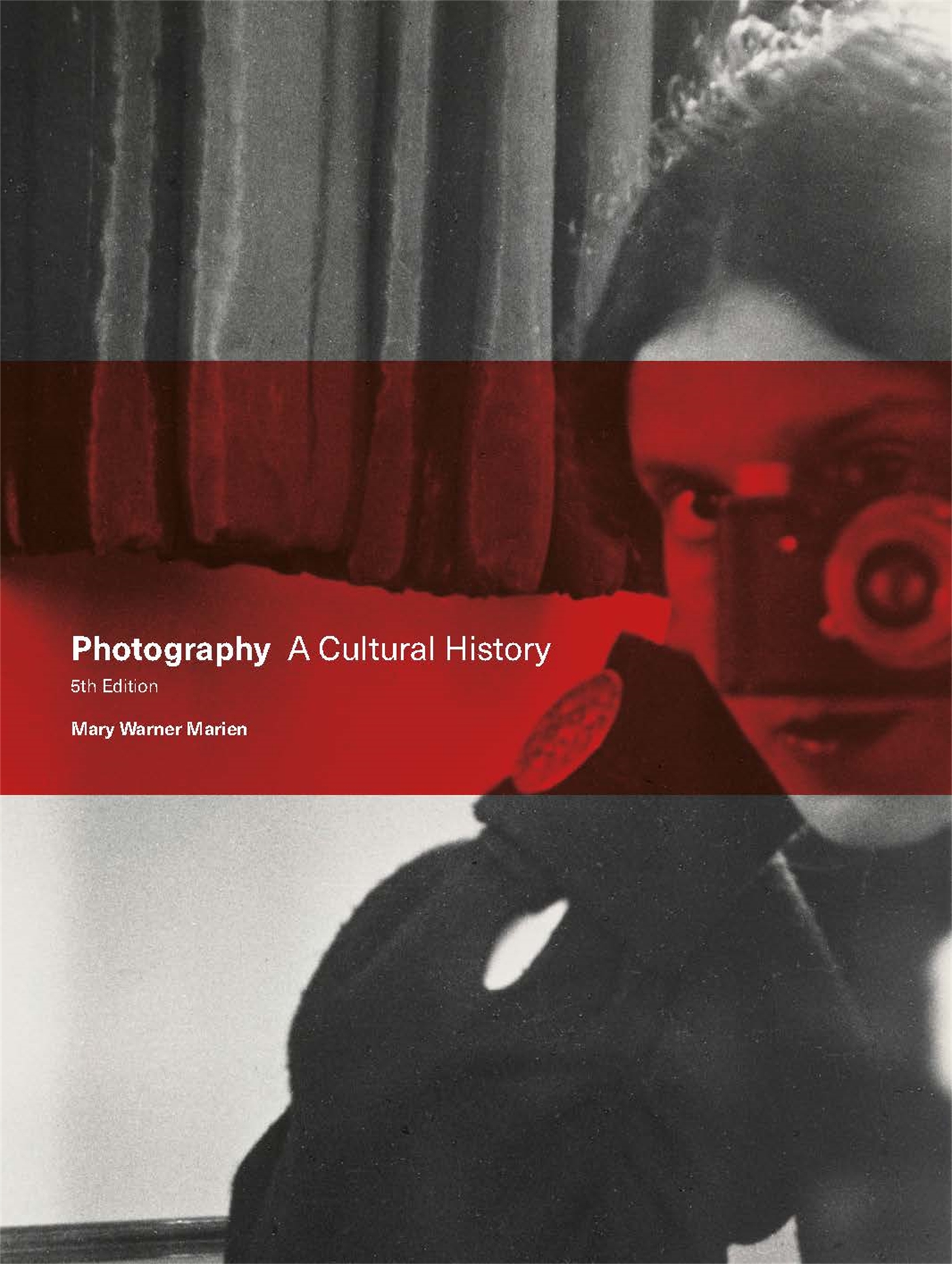

Photography

A Cultural History

FIFTH EDITION

Photography

A Cultural History

FIFTH EDITION

Mary Warner Marien

Laurence King Publishing

An imprint of Quercus Editions Ltd

www.laurenceking.com/student/

First published in Great Britain in 2021 by

Laurence King Student & Professional

An imprint of Quercus Editions Ltd

Carmelite House

50 Victoria Embankment

London EC4Y 0DZ

An Hachette UK company

Copyright 2021, 2014, 2010, 2006, 2002 Laurence King Student & Professional, an imprint of Quercus Editions Ltd (formerly Laurence King Publishing Ltd)

The moral right of Mary Warner Marien to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

PB ISBN 978 1 78627 785 5

Ebook ISBN 978 1 52942 0 975

Quercus Editions Ltd hereby exclude all liability to the extent permitted by law for any errors or omissions in this book and for any loss, damage or expense (whether direct or indirect) suffered by a third party relying on any information contained in this book.

Origination by DL Imaging, London

Cover design by Alex Wright

Cover: ILSE BING, Self-Portrait with Leica Camera, Paris, 1931.

Copyright Estate of Ilse Bing.

Frontispiece: ATONG ATEM, Self-Portrait in Gingham, 2018.

Digital photograph. Courtesy the artist and Mars Gallery, Victoria, Australia.

CONTENTS

Preface

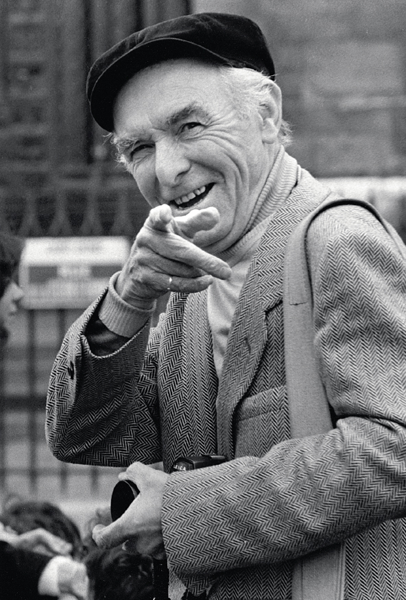

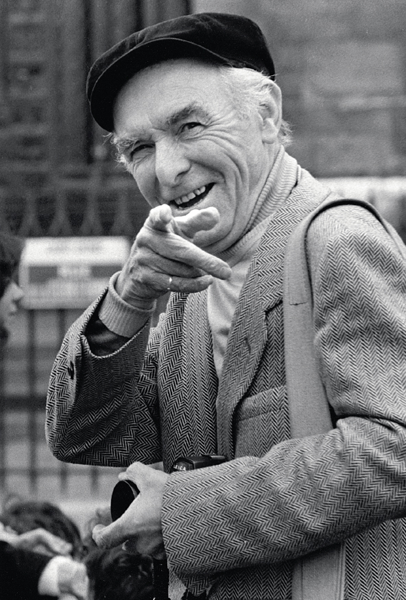

Despite the impressive increase in college photography courses, autodidacts such as myself make up the bulk of photohistorians. Like many others, I became a photographic historian in my parents living-room, while looking at copies of Life magazine. We photohistorians revel in our passionate preferences. If I had thought I could get away with it, I would have filled this book with my favorite pictures, such as those that French photographer Robert Doisneau made of Paris in the 1950s and 1960s. I have not yet found a tactic to show Doisneaus work in my survey, but have reproduced the portrait that is pinned above my desk: a broadly grinning Doisneau pointing directly at me, prompting me to expect the unexpected ().

1 GERARD MONICO, Robert Doisneau, 1986.

In writing this book, I have tried to survey photographys history in such a way that readers can gauge the mediums manifold developments, and appreciate the historical and cultural contexts in which photographers lived and worked. Some readers may long for a comprehensive taxonomy of photography, a unified field with movements and ideas carefully delineated like kingdoms, phyla, orders, and species. Indeed, this sort of categorization is a practical, if sometimes blunt, instrument with which to create order and highlight dominant ideas and visual approaches. Yet it is crucial to remember that people living in a particular era do not synchronize their thoughts. They interpret, refine, resist, oppose, or ignore the prevalent attitudes of their time. Years of teaching have brought home to me the dangers of homogenizing subtly distinctive viewpoints or creating periods so watertight that they leave no residue in the next chapter.

My students have taught me that, contrary to conventional wisdom, they do not dislike history, but are instead hungry for it. Consequently, I have tried to sketch the political and economic events that shaped the circumstances in which photography was practiced, while paying special attention to the particular ideas generated by and about photography in each period. Each Part concludes with a Philosophy and Practice section, centered on how beliefs shaped photographic practice. In addition, the Focus boxes in this book discuss particular ideas and historical moments.

Photography generates its own special excitement, in part because it quickly reacts to encompass fresh material and new analytic tools, underscoring its vital, interdisciplinary character. Although photography was a Western discovery, students are rightly curious about its many manifestations in the wider world. To serve that interest, I have incorporated both recent research into non-Western photographers and Western visions of the non-Western world as they were directed toward science, anthropology, journalism, and art.

I am mindful that, despite the existence of several lengthy histories and many monographs, comprehensive surveys of photography in Asia (which makes up about 60 per cent of the worlds population) have yet to be created, though scholars in China and India are pursuing this goal. As the numbers of photographers and historians from these countries increase, so too does the opportunity for wide-ranging historical recall. Although photography became a business in its first decade, the photographic archives of business and industry have scarcely been mined, and the history of advertising photography, which has shaped the modern experience internationally, remains mostly unwritten.

Influential photographers have often led long lives, traversing eras during which many changes took place. For example, Alfred Stieglitz (18641946) was born one year before the American Civil War ended, and he died one year after World War II finished. Having taught an introductory course, I realized that newcomers to the field appreciate an overview of individual careers such as that of Stieglitz, even if this occasionally requires disrupting the chronological order of the presentation. Hence I have included a number of Portrait boxes that concentrate on certain influential photographers.

I have discovered in the classroom that todays students, accustomed to encountering art and documentary expression in non-traditional media, are puzzled by the lengthy struggle waged through the nineteenth and twentieth centuries to have photography accepted as an art form. I have narrated that contest, not simply as a large-scale attempt to achieve parity with painting, but as it relates to wider social issues, such as the ascent of a professional, moneyed middle class and the rise of consumer culture.

At present, globalization and digital media encourage the convergence and blurring of photographic genres: photojournalists show their work in art galleries; photographers create new websites to foster social change; practitioners from developing countries depict indigenous motifs using digital tools. The computer, inventedas its name suggeststo facilitate computations, spun a technology and a communications network that are actively investigated and refined by photographers from many fields. Along with my student colleagues, I am intrigued by emerging visual technologies, and I have concluded this survey with a review of the digital tools as well as some of the trends that have shaped the first two decades of the twenty-first century.