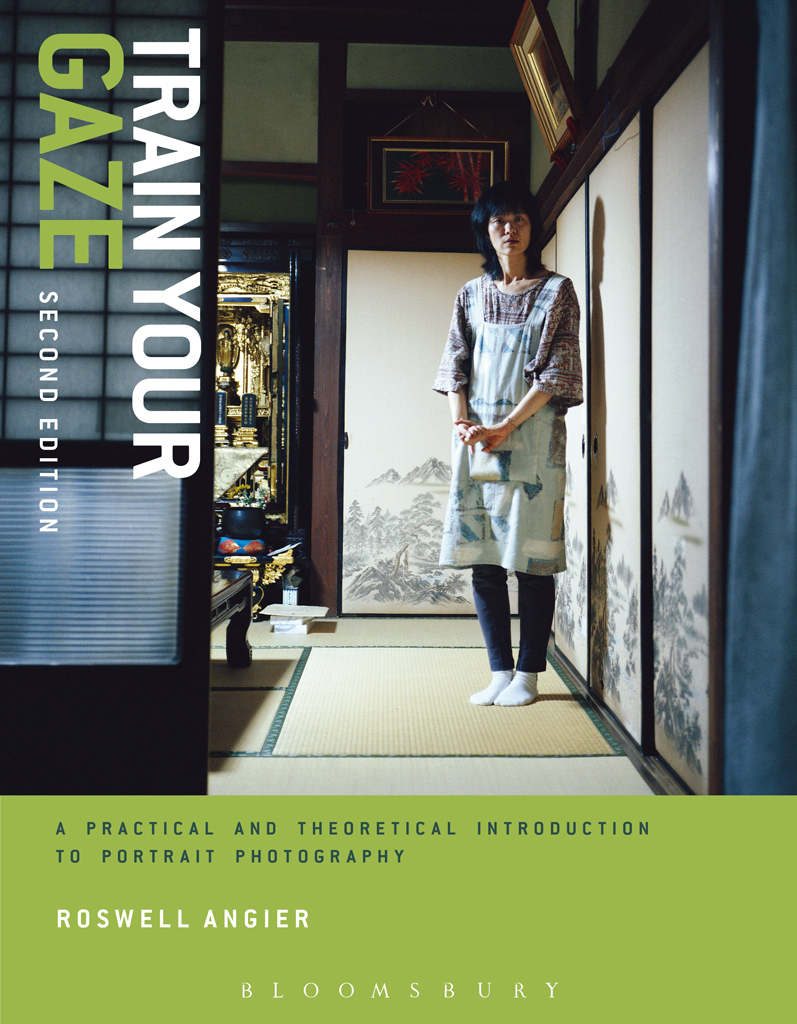

Roswell Angier is currently a faculty member at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, USA. Roswell has enjoyed a rewarding career as both a photographer and educator, and has worked as a freelance magazine photographer and been a partner in a co-operative photographic agency in New York. Many of his images are held in prestigious collections, including the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, the Smithsonian Museum, the Addison Gallery of American Art and private collections around the world.

Also available from Bloomsbury:

Behind the Image: Research in Photography

Reading Photographs: An Introduction to the Theory and Meaning of Images

Perspectives on Place: Theory and Practice in Landscape Photography

www.fairchildbooks.com

www.bloomsbury.com

CONTENTS

PREFACE

This book is about photographing people, in many different ways and from various perspectives. It is meant for an audience already acquainted with photography. Basic competence with cameras, darkrooms, and/or image-processing software is assumed. Discussion of purely technical issues is limited to key elements of the image-capture process and can be found chiefly in the three appendices (see below for instructions on how to access the online appendices).

The book is by no means a manual, but it is practical. It examines the content of a photograph, discussing history, theory, and formal analysis along the way.

The book devotes a great deal of attention to different aspects of the picture-making process and to the conditions surrounding that process. Because scrutiny and interpretation of other photographers work is an integral part of ones own practice, it presents and analyzes images by many photographers. Some of these images are portraits in the classic sense; others stretch the boundaries of portraiture as a distinct genre. What is common to all of them is the presence of a human subject and the photographers thoughtful regardthe felt activity of someone looking, the photographer embedded in the image.

The catalyzing element in a photograph might be a moment exchanged between the photographer and the subject, an inadvertent spark in the empty space between them. It could be a long and steadfast stare, embodying the photographers unformed but intense desire for a good photograph. Or it might be something stealthy, a quietly fascinated gaze thrown out like a fishing line at an unwary subject, with the hope of seizing some trace of that persons singularity. As much as anything else, cultivating and activating this presence, this way of looking, is what this book is about.

Student resources to accompany this book are available at:

Please follow this link and follow the instructions to the online resources . If you have any problems, please contact

CHAPTER 1

ABOUT LOOKING

SCIENCE INTERPRETS THE GAZE IN THREE (COMBINABLE) WAYS; IN TERMS OF INFORMATION (THE GAZE INFORMS), IN TERMS OF RELATION (GAZES ARE EXCHANGED), IN TERMS OF POSSESSION (BY THE GAZE, I TOUCH, I SEIZE, I AM SEIZED).... BUT THE GAZE SEEKS: SOMETHING, SOMEONE. IT IS AN ANXIOUS SIGN: SINGULAR DYNAMICS FOR A SIGN: ITS POWER OVERFLOWS IT.

ROLAND BARTHES

Y ou are alone with your subject. The room is silent. Neither of you is talking. You stare, concentrating on minor variations of facial expression, body language, gesture. You move slowly, carefully. The camera is mounted on a tripod. The subject is stationary, but her eyes follow you as you move from side to side. Occasionally, one of her hands drifts downward toward a pocket or upward toward her face. She closes her eyes for a moment, reopens them. An eyebrow shoots up, as if to register a sudden thought.

Now. You squeeze the bulb at the end of the cable release, exposing a frame. You advance the film to the next frame. You wait for something else to happen, a facial expression or minor gestural event. The nervous tension youve been feeling, from not speaking to each other for what seems like a long time, is starting to subside. You are now almost in a trance. You take another picture. You advance the film again. You take another picture. You have fallen into the circle of your own gaze. Youre in fascination time.

CREATING SILENCE

In the late 1960s, Richard Avedon published a series of portraits in Rolling Stone called The Family. The pictures were of powerful people, mostly men. The subjects were evenly lit by ambient light, without a hint of shadow, posed in Avedons signature setting, against stark white backdrop paper. They seemed uneasy, many of them uncertain of what to do with their hands, some of them seeming to be collapsed inward on themselves but nonetheless determined to face the camera.

Looking at these portraits, one feels the silence as a tangible presence. It was rumored that Avedon did not speak to his subjects while he was shooting. They were ushered into his studio by an assistant and told to align their feet with a mark on the floor. The camera, an imposing 8" 10" view camera mounted on a tripod, had been focused in advance, using an assistant as a stand-in for the subject. For the entire session, according to legend, the photographer would walk around the room, tethered to the camera by a long cable release, staring. After each exposure, an assistant would change the film holder, and the staring would resume. The result was a series of portraits in which the subjects own presence was engulfed by the intensity of the photographers gaze. Sometimes the subject would stare back aggressively, but there was never any doubt about who was in control.

Avedon used a similar procedure in In the American West, in which he photographed drifters, miners, housekeepers, factory workers, inmates, cowboys, itinerant preachers. The subjects were social types, carefully chosen for the ways in which they represented the old frontier culture of America. In the pictures they often look haunted or intimidated; in some of them, a hint of defiance is evident. Only a single subjecta Navajo rodeo cowboysmiles.

These photographs communicate the sense that the subjects are hanging on to their identities by a thread. Avedon achieves this effect largely by relying on the overpowering presence of the camera. Whatever they may suggest of the social fabric, his portraits are not documentary. They are not intended to be dispassionate or objective; they are certainly not friendly or compassionate. They are aggressive personal statements. In an introductory comment to this work, Avedon said that he thought all portraits, especially his own, were opinions. The photographers eye here does not seek merely to represent. Its goal is to persuade. Its nature is predatory and confrontational.

In the early days of photography, when emulsions and lenses were slow just about the only thing the camera was good for was confrontation: the creation of an image in which the subject was required to squarely face the camera and to hold still for a long exposure. Being photographed was a ceremony that lent a special quality to the resulting image, one that is hard to replicate with modern equipment. To the extent that Avedons portrait work has a rigorous ceremonial feeling, it is because of its affinity with the daguerreotype esthetic.

It is possible to make confrontational images with modern film and imaging devices. Modern cameras loaded with fast film (or digital cameras with a high ISO setting) can easily produce one kind of stillness: they can freeze motion with a fast shutter speed. But for the subject to produce an effect of profound motionlessness, the photographer must revert to the set of conditions imposed on the daguerreotypist. The subject must not only be told to remain motionless, but to be quiet.