2012 by the University of New Mexico Press

All rights reserved. Published 2012

Printed in the United States of America

17 16 15 14 13 12 1 2 3 4 5 6

THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS HAS CATALOGED THE PRINTED EDITION AS

FOLLOWS:

Lawson, Russell M., 1957

Frontier naturalist : Jean Louis Berlandier and the exploration of northern Mexico

and Texas / Russell M. Lawson.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8263-5217-0 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-8263-5219-4 (electronic),

1. Mexico, NorthDescription and travel. 2. Texas, SouthDescription and travel.

3. Berlandier, Jean Louis, d. 1851Travel. 4. Natural historyMexico, North.

5. Natural historyTexas, South. 6. Scientific expeditionsMexico, North

History19th century. 7. Scientific expeditionsTexas, SouthHistory19th century.

8. NaturalistsFranceBiography. 9. ExplorersMexico, NorthBiography.

10. ExplorersTexas, SouthBiography. I. Title.

F1314.L39 2012

508.72dc23

2012018873

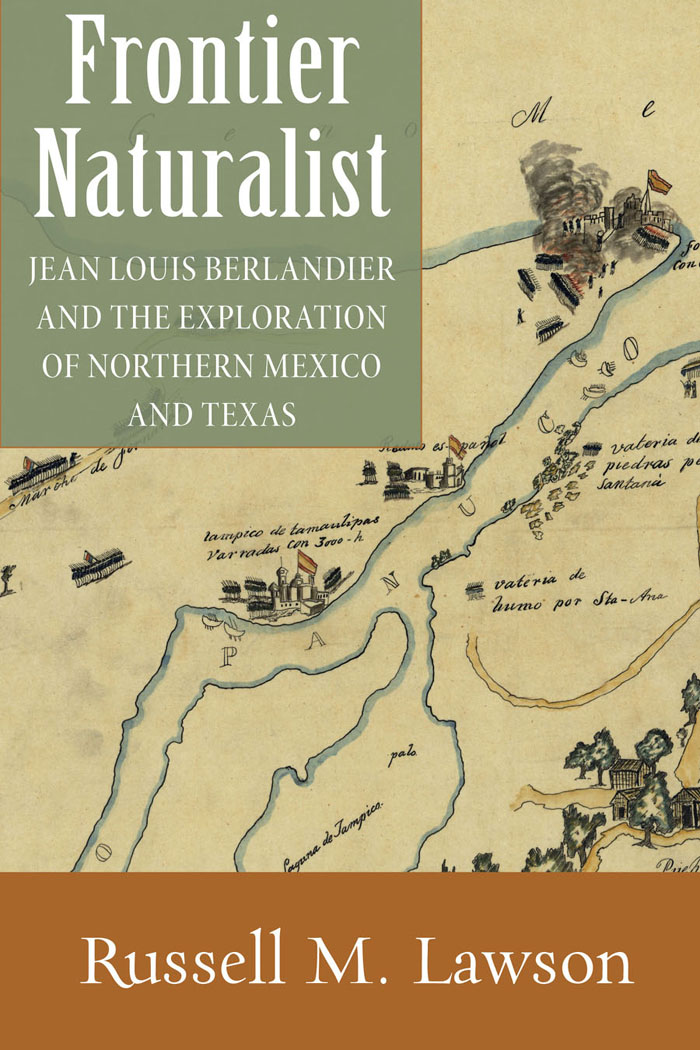

Cover image: Map depicting battle against Isidro Barradas in vicinity of

Tampico, Mexico, in 1829. Copied from the original by Lt. Charles N. Hagner,

Topographical Engineers. Library of Congress.

For Pooh, again.

Acknowledgments

I wish to express my thanks to many institutions for support and to individuals for help during the writing of this book. I appreciate the financial assistance of the professional development fund and the support of the administration at Bacone College. I received assistance from archivists and librarians at Gilcrease Museum, Beinecke Library at Yale University, Gray Herbarium at Harvard University, Old Colony Historical Society, Smithsonian Institution Archives, Ewell Sale Stewart Library and Archives at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, and Bacone College.

Thanks also to several anonymous readers who provided helpful criticisms about the manuscript; staff members of the University of New Mexico Press, past and present, such as Luther Wilson, W. Clark Whitehorn, Elise McHugh, and Felicia Cedillos; and copyeditor Lisa Williams.

I wish to thank my son, Benjamin A. Lawson, a PhD candidate in history at the University of Iowa, for drawing the map of Berlandiers travels. My wife, Linda Lawson, read a draft of the manuscript and provided helpful suggestions. This book is dedicated to her.

Introduction

This is a story of discovery. the setting is a land of extremes: in temperature, the heat of the

terra caliente and the cold of the Sierras; in moisture, the arid lands of the Mexican Plateau and the humidity of the lowlands near the sea; in elevation, ranging from 10,000 feet in the mountains to sea level along coastal waters; in nature, peaceful and calm on summer evenings along

parajes, camping places next to ponds and rivers, and violent and terrifying when storms from the northern plains roll across the plains to the south and east. This is a story about discoverers: inquisitive, courageous people of constancy and perseverance. Featured are a Frenchman educated in Geneva living in Mexico; an American scientist and soldier, veteran of the Mexican War; Mexican scientists and soldiers; Tejano settlers and American filibusters; and indigenous hunters, warriors, and guides. The northern Mexican and southern Texas frontiers from 1826 to 1853, the chronological boundaries of this narrative, were under contention by different peoples: Comanches and Lipan Apaches, squatters and colonists from the United States, and mestizo settlers from south of the Ro Bravo del Nortethe Rio Grande. Among all of these peoples were those who are never content with what is and who one is, who seek to go beyond what is known to what can be known, who are restless to find and, having found, to find again. Discoverers typically have motives that include wealth, glory, and knowledge. The discoverers portrayed herein were of the latter sort, wanting to know for the sake of knowing; to extend themselves outward, restlessly, into the natural environment; to contribute to a broadening of institutional knowledge in libraries, museums, institutes, and associations. Beyond these lofty goals, on the trail discoverers sought to take the best paths to go from here to there, to ensure water to drink, food to eat, shelter from the elements, and protection from enemies.

The spring of 1828 was a particularly wet one on the northern Mexican frontier. The varied people who inhabited the rivers of Texas, particularly the Colorado, Brazos, and Trinity, had rarely seen the waters rise so high, making tall oaks seem like huge bushes floating on the surface. Freshets inundated entire valleys, destroying crops and farms, impoverishing people already desperately poor. Old Spanish roads that traversed the land from San Antonio de Bxar to Nacogdoches were washed out in some places and soggy, sticky clay in others. Only a fool would travel this way except through utter necessity, and the only travel that made any sense was by mule or on horseback. And yet, to the astonishment of the Tejanos, the Mexicans of the gulf plain of Texas, during April, May, and June of that year a large caravan of soldiers, who did not appear quite like typical Mexican soldiers, sloshed, splattered, and cursed their way along the caminos of Texas. What was unusual about this group of soldiers was their stated aim and commensurate behavior, seeking knowledge rather than booty; their wagons, loaded with strange-looking equipment, one decked out in gilded finery; and their members, at least one of whom was not armed, nor dressed in a uniform. This latter member of the troop was constantly straying from the caravan, disappearing into woods and over hills into meadows. He carried a satchel into which he put plants, roots, leaves, and flowers. He frequently halted to write something in a journal he carried, and sometimes he seemed to be sketching something he spied in the distance. The man was young, and he spoke with a strange accent. His English was very poor and his Spanish little better; when he spoke with confidence it was in French. This traveler among the American squatters and colonists, the Mexican immigrants from south of the Rio Grande, and the Indians, most of whom were recent arrivals from north of the Red River, was a native Frenchman, a Swiss scientist, a newcomer to the northern Mexican and southern Texas frontiers: Berlandier.

Albuquerque

Albuquerque

I wish to express my thanks to many institutions for support and to individuals for help during the writing of this book. I appreciate the financial assistance of the professional development fund and the support of the administration at Bacone College. I received assistance from archivists and librarians at Gilcrease Museum, Beinecke Library at Yale University, Gray Herbarium at Harvard University, Old Colony Historical Society, Smithsonian Institution Archives, Ewell Sale Stewart Library and Archives at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, and Bacone College.

I wish to express my thanks to many institutions for support and to individuals for help during the writing of this book. I appreciate the financial assistance of the professional development fund and the support of the administration at Bacone College. I received assistance from archivists and librarians at Gilcrease Museum, Beinecke Library at Yale University, Gray Herbarium at Harvard University, Old Colony Historical Society, Smithsonian Institution Archives, Ewell Sale Stewart Library and Archives at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, and Bacone College.

This is a story of discovery. the setting is a land of extremes: in temperature, the heat of the terra caliente and the cold of the Sierras; in moisture, the arid lands of the Mexican Plateau and the humidity of the lowlands near the sea; in elevation, ranging from 10,000 feet in the mountains to sea level along coastal waters; in nature, peaceful and calm on summer evenings along parajes, camping places next to ponds and rivers, and violent and terrifying when storms from the northern plains roll across the plains to the south and east. This is a story about discoverers: inquisitive, courageous people of constancy and perseverance. Featured are a Frenchman educated in Geneva living in Mexico; an American scientist and soldier, veteran of the Mexican War; Mexican scientists and soldiers; Tejano settlers and American filibusters; and indigenous hunters, warriors, and guides. The northern Mexican and southern Texas frontiers from 1826 to 1853, the chronological boundaries of this narrative, were under contention by different peoples: Comanches and Lipan Apaches, squatters and colonists from the United States, and mestizo settlers from south of the Ro Bravo del Nortethe Rio Grande. Among all of these peoples were those who are never content with what is and who one is, who seek to go beyond what is known to what can be known, who are restless to find and, having found, to find again. Discoverers typically have motives that include wealth, glory, and knowledge. The discoverers portrayed herein were of the latter sort, wanting to know for the sake of knowing; to extend themselves outward, restlessly, into the natural environment; to contribute to a broadening of institutional knowledge in libraries, museums, institutes, and associations. Beyond these lofty goals, on the trail discoverers sought to take the best paths to go from here to there, to ensure water to drink, food to eat, shelter from the elements, and protection from enemies.

This is a story of discovery. the setting is a land of extremes: in temperature, the heat of the terra caliente and the cold of the Sierras; in moisture, the arid lands of the Mexican Plateau and the humidity of the lowlands near the sea; in elevation, ranging from 10,000 feet in the mountains to sea level along coastal waters; in nature, peaceful and calm on summer evenings along parajes, camping places next to ponds and rivers, and violent and terrifying when storms from the northern plains roll across the plains to the south and east. This is a story about discoverers: inquisitive, courageous people of constancy and perseverance. Featured are a Frenchman educated in Geneva living in Mexico; an American scientist and soldier, veteran of the Mexican War; Mexican scientists and soldiers; Tejano settlers and American filibusters; and indigenous hunters, warriors, and guides. The northern Mexican and southern Texas frontiers from 1826 to 1853, the chronological boundaries of this narrative, were under contention by different peoples: Comanches and Lipan Apaches, squatters and colonists from the United States, and mestizo settlers from south of the Ro Bravo del Nortethe Rio Grande. Among all of these peoples were those who are never content with what is and who one is, who seek to go beyond what is known to what can be known, who are restless to find and, having found, to find again. Discoverers typically have motives that include wealth, glory, and knowledge. The discoverers portrayed herein were of the latter sort, wanting to know for the sake of knowing; to extend themselves outward, restlessly, into the natural environment; to contribute to a broadening of institutional knowledge in libraries, museums, institutes, and associations. Beyond these lofty goals, on the trail discoverers sought to take the best paths to go from here to there, to ensure water to drink, food to eat, shelter from the elements, and protection from enemies.