BFI Film Classics

The BFI Film Classics is a series of books that introduces, interprets and celebrates landmarks of world cinema. Each volume offers an argument for the films classic status, together with discussion of its production and reception history, its place within a genre or national cinema, an account of its technical and aesthetic importance, and in many cases, the authors personal response to the film.

For a full list of titles available in the series, please visit our website:

Magnificently concentrated examples of flowing freeform critical poetry.

Uncut

A formidable body of work collectively generating some fascinating insights into the evolution of cinema.

Times Higher Education Supplement

The series is a landmark in film criticism.

Quarterly Review of Film and Video

Editorial Advisory Board

Geoff Andrew, British Film Institute

Edward Buscombe

William Germano, The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art

Lalitha Gopalan, University of Texas at Austin

Lee Grieveson, University College London

Nick James, Editor, Sight & Sound

Laura Mulvey, Birkbeck College, University of London

Alastair Phillips, University of Warwick

Dana Polan, New York University

B. Ruby Rich, University of California, Santa Cruz

Amy Villarejo, Cornell University

For Isabel

Contents

I am grateful to Rebecca Barden and the BFI Film Classics board for supporting the inclusion of this volume in the series. My thanks are also due to the anonymous BFI Classics readers for their helpful comments on an earlier draft, Sophia Contento at BFI Publishing, the British Academy for a grant enabling me to research archives in Los Angeles, Laura Mulvey for her encouragement and for refereeing my BA grant application, Jon Halliday for helpful comments and suggestions, the Margaret Herrick Library of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (especially Barbara Hall), as well as the UCLA (especially Lauren Buisson) and USC (especially Ned Comstock) libraries, where I carried out most of the research for this volume. I also consulted material at the Queen Mary, University of London Library, the British Library, the British Film Institute Library, the University of Roehampton Library and the University of London Senate House Library. I am grateful and indebted to my colleagues in the Department of Film Studies, in the School of Languages, Linguistics and Film, Queen Mary, University of London, as well as, more generally in the School, to Jill Evans and Rdiger Goerner. Katie-Jane Hext, Ron Guariento, Andrea Sabbadini, Christopher Cordess, Carine Ronsmans, the Fulham film club, Prue Downing, Louise Riley-Smith, Philippa Hudson, Marta Rey and Carlos Troncoso also helped and encouraged me in various ways. Bruce Babington, my friend and collaborator over many years, and co-author of our publications that began with a 1990 Movie article on Sirk, ran his expert eye over an early draft and made many useful suggestions. Isabel, Tom, Jenni, Phil, Tabitha, Michael and family were a source of much-needed encouragement during the later stages of the writing of this book. Isabels insights and suggestions have been, as ever, indispensable. This book is dedicated to her.

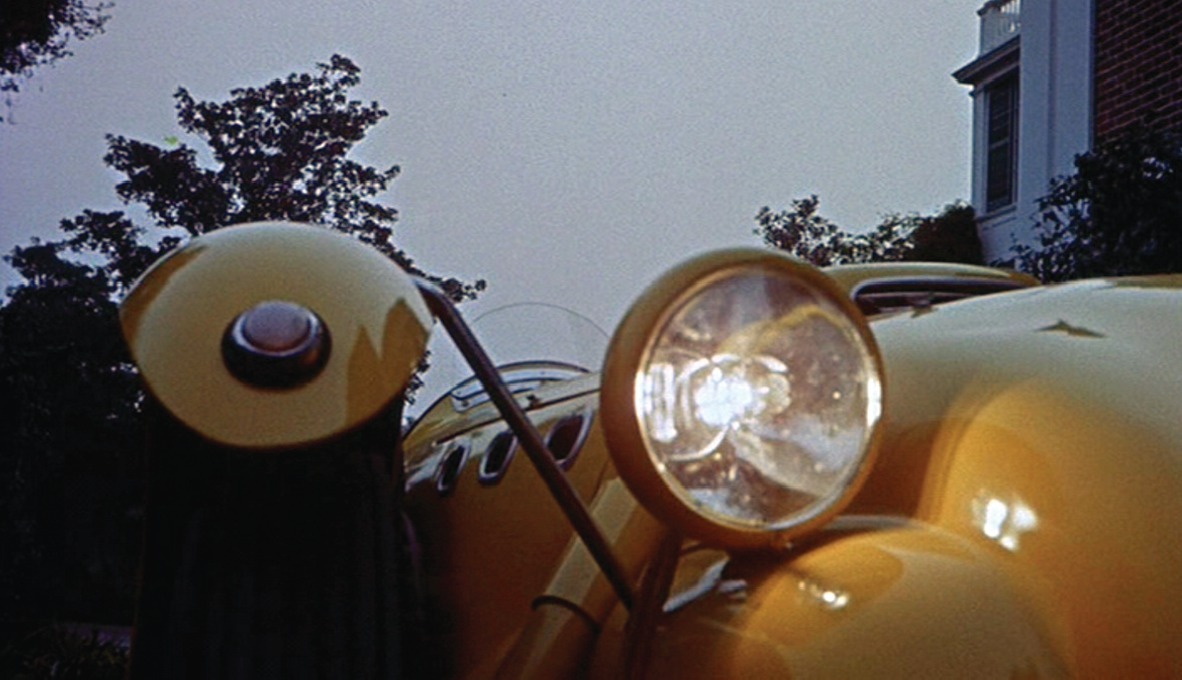

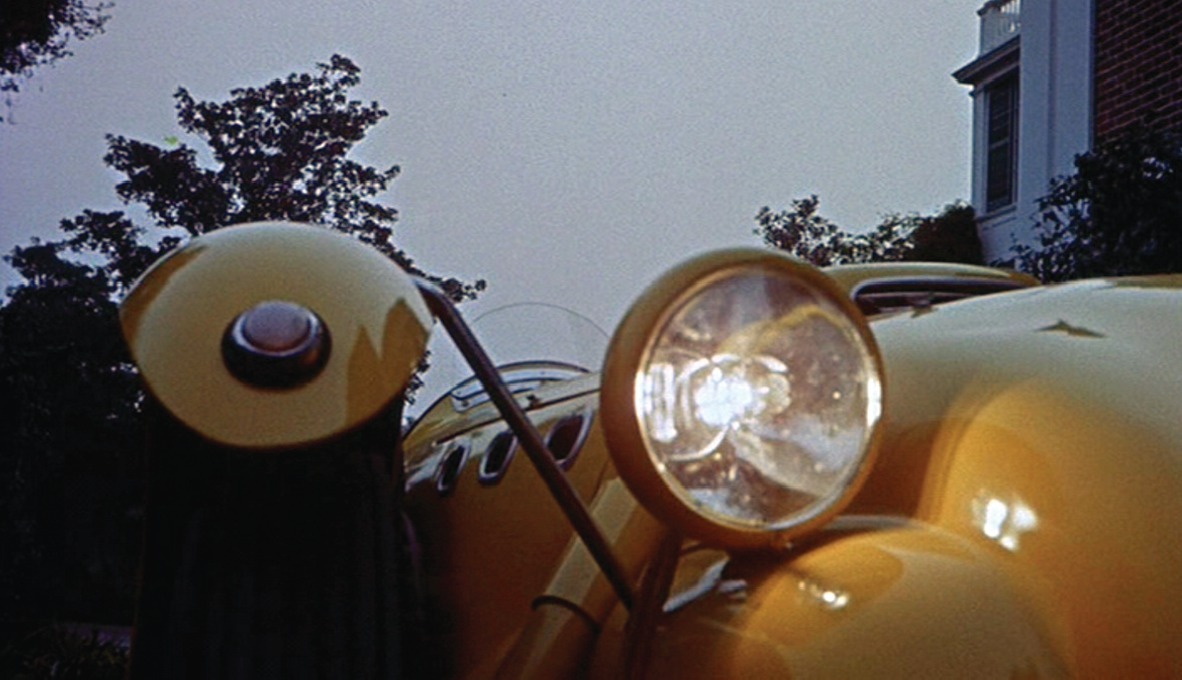

As a yellow 1953 Allard J2X hot rod driven by Kyle Hadley (Robert Stack) scorches through a Texan Monument Valley of derricks and telegraph poles, heading towards Hadley, an oil town, Frank Skinners portentous music, carried initially by predominantly brass instruments, warns of impending catastrophe, the melos in the drama, in Charles Rosens words, shaping our perceptions of a narrative (Rosen 2011: 11).

Even before the medium shot of the reckless drivers swig at a bottle of raw corn, the seventh in a montage of eight shots showing the car racing past from left to right, the doom-laden orchestral score followed by a song composed specially for the film bind together a dazzling sequence of sights and sounds to announce the films themes. Sirks brilliant matching of the vitality of form and morbidity of theme introduces his survey of a desperate class through a burst of furious cinematic energy unparalleled elsewhere in his work.

Racing through a hellish landscape

Symbols of the power elite; Kyle driven by inner furies

Eventually, the driver halts his roadster at the entrance of the antebellum mansion (hired for exteriors by the studio from the gambling and uranium holdings millionaire, Samuel Kingston). The rapid but cheerless tempo of the opening bars yields to the slower, lilting melodic cadences and elegiac lyrics of the Victor YoungSammy Cahn tune sung by the Four Aces, accompanying the credits and preparing the way for its first line, A faithless lovers kiss, delivered against the visual backdrop of a window frame, seen from outside the building.

To the right, in the foreground, stands a dark-suited Mitch Wayne (Rock Hudson), his eyes staring pensively out of the frame and into the darkness beyond. The bottom left of the frame shows Lucy Moore/Hadley (Lauren Bacall), lying in bed, dressed in a cream-coloured negligee.

The words, A faithless lovers kiss, refer to infidelity, but the visual imagery is ambiguous: a woman faithless or faithful? moves to occupy centre frame. Whether, alternatively, the man looking out of her bedroom window is innocent or guilty of infidelity is also at this stage an open question. Played by Rock Hudson, already a Hollywood hero, whose name now appears on the screen, Mitch, unlike Lucy, and significantly wearing day clothes, seems an implausible betrayer, though later revelations confirm guilt of thought, even if not of word and deed. The cameras position outside the window distances the viewer from the characters, and seems to frame them together in a world of airless hedonism, sheltered from natures windblown domain outside.

The next verse, Is written on the wind, guides the viewer to a low-angle shot of the hot rod that comes to an abrupt halt in the

Mitch still framed by the Hadleys

Kyles roadster as dual symbol of petro-dollar luxury and perception

The driver alights and approaches the mansion, while the perspective now shifts to a medium shot of the bedroom interior, where Lucy attempts vainly to leave her bed, flopping down again, numbed and unable to face the brewing tragedy. Even when she does manage it, at the end of the scene, she collapses, as if swathed in what looks like a winding sheet, the billowing curtain of her luxurious morgue-like bedroom. Accompanying the words A night of stolen bliss in the score, Lauren Bacalls name appears, given the same size lettering as Hudsons, and in line with her agents demands: