Publication of this volume was made possible in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Frontispiece: Mark Twain, 1907. (Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, reproduction # LC-USZ62-5513)

Battle Hymn of the Republic (Brought Down to Date) reprinted by permission of the Mark Twain Foundation; Campaigning with Mark Twain by Absalom Grimes reprinted by permission of Yale University Press.

Copyright 2007 by The University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth,

serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved.

Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky

663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008

www.kentuckypress.com

11 10 09 08 07 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Twain, Mark, 1835-1910.

[Selections. 2007]

Mark Twains Civil War / edited by David Rachels.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8131-2474-2 (hardcover: alk. paper)

1. United StatesHistoryCivil War, 1861-1865Literary collections.

2. United StatesHistoryCivil War, 1861-1865Literature and the war.

I. Rachels, David. II. Title.

PS1303.R33 2007

818\409-dc22 2007028706

This book is printed on acid-free recycled paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America.

| Member of the Association of American University Presses |

Introduction

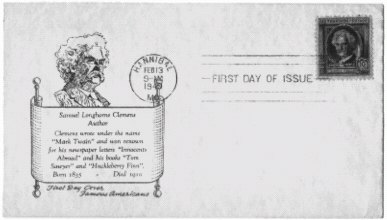

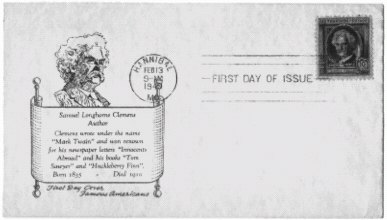

On January 24, 1940, after New York Congressman Samuel Dicksteins impassioned speech condemning Nazi atrocities against Polish Jews, talk in the U.S. House of Representatives turned to domestic matters. Representative William Jennings Miller of Connecticut took the floor to discuss the Famous Americans series of postage stamps. The first five stamps in the series were to honor authors. The first two, picturing Washington Irving and James Fenimore Cooper, would go on sale in five days. The Irving stamp would be sold first in Tarrytown, New York, where Irving had lived the final years of his life; the Cooper stamp would be sold first in Cooperstown, New York, his boyhood home. Stamps honoring Ralph Waldo Emerson and Louisa May Alcott would follow on February 5, first appearing in Boston, Massachusetts, and Concord, New Hampshire, respectively. The final author stamp, featuring Mark Twain, was scheduled to debut on February 13 in Hannibal, Missouri. But Congressman Miller wondered if Hannibal were the proper place for launching the Twain stamp. Consulting Albert Bigelow Paines biography of Twain, Miller had discovered that Twain was not born in Hannibal. Furthermore, Miller learned that the famous writer had lived in Hannibal for only five years (although fourteen years is closer to the truth). By contrast, Twain lived in Hartford, Connecticutin Millers congressional districtfor forty-three years. Most of his well-known works, Miller noted, were written and published in Hartford. Thus, Miller requested that the Twain stamps be divided between Hannibal and Hartford, with at least half going to Connecticut.

(Collection of David Rachels)

The following day Representative Joseph B. Shannon of Missouri responded. Surprisingly, Shannon declared that, as far as he was concerned, Connecticut could have all the stamps, for Mark Twain was not of the same kidney as real Missourians. At issue was Twains service during the Civil War. On the floor of Congress, Shannon gave this largely inaccurate summary of Twains military career:

When the call to arms came, he was living in Hannibal. Col. Jack Burbridge, of Pike County, organized the Confederate forces in that portion of Missouri. A meeting was held at Hannibal for the purpose of enlisting men to fight for the Confederacy. The colonel took charge of the meeting, which was well attended. Among those who were there on that night was Mark Twain. Mark joined the forces and became a lieutenant.

His company had no sooner organized, however, when a fighting Kentucky Democrat, Frank P. Blair organized four regiments in eastern Missouri and offered these regiments to the Union cause. These soldiers gave contest to Colonel Burbridge and his forces in northern Missouri. Colonel Burbridge met them, and so did Mark Twainfor a few moments only. Mark Twain met them; and, as someone said, a Mini ball came whizzing past his ball came whizzing past his ears, and he started running. He ran; and, oh, how fast he did run. He never stopped until he got to Keokuk, Iowa. Colonel Burbridge fought 4 years in the Southern Army; Mark Twain about 4 minutes.

Though Twains four minutes were actually two weeks, no credible evidence indicates that he ever saw anything resembling combat. Shannon concluded his fanciful remarks by quoting the company commander of the Burbridge Brigade: We went to war. We remained at war for 4 years. We came back home. I can say to my fellow Missourians that we had but one coward in our whole group, and his name was Samuel L. Clemens.

Representative Miller of Connecticut, a legless veteran of World War I, did not come to Twains defense. Rather, he interrupted his colleague only once to ask a clarifying question: I take it the gentleman from Missouri would be just as well satisfied if the Mark Twain commemorative stamp were put on sale elsewhere?

Twain would be defended, after a fashion, two weeks later in the New York Times. In an article prompted by Congressman Shannons comments, the newspaper opined, Whether the desertion was anything more than technical, one doesnt know or care. On both sides that war was singularly rich in desertions. Lieutenant Clemens might have been killed, instead of completing his education. So we praise his absquatulation as we do Horace for abandoning his shield. In other words, had Sam Clemens been killed, there would have been no Mark Twain. True enough. At the time of the war, however, there was no reason for Clemensor anyone else, for that matterto suspect that he would later become Mark Twain. We may be glad, in retrospect, that he fled the war, but our hindsight has nothing to do with his wartime behavior and its possible justifications.

In addition to charges of cowardice, Twain has been faulted for fighting on the wrong side in the war (inasmuch as he fought at all). In March 1901, for example, when Twain condemned American troops for participating in a land-stealing and liberty-crucifying crusade in the Philippines, the

Edited by

Edited by

![Twain Mark - Autobiography of Mark Twain Vol. 1 / associate eds. Benjamin Griffin ... [et al.]](/uploads/posts/book/210276/thumbs/twain-mark-autobiography-of-mark-twain-vol-1.jpg)