First published in 1994 by Routledge

First published in paperback 1996

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada

by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

1994, 1996 Michael Grant Publications Ltd

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

ISBN 0-415-13814-0

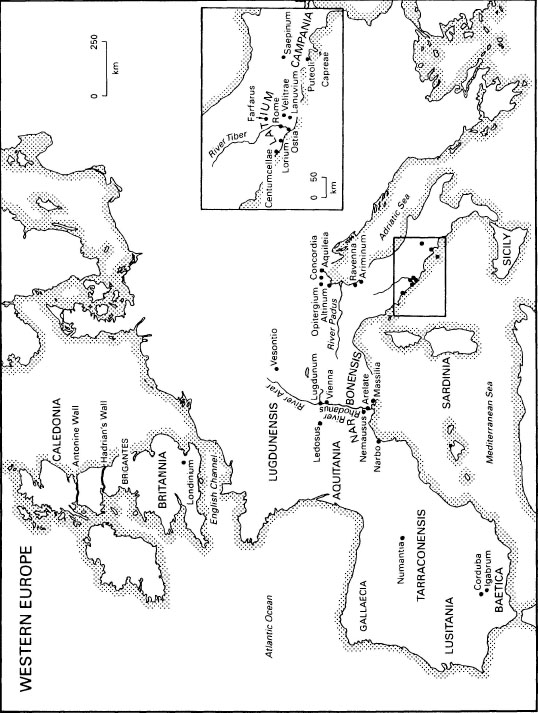

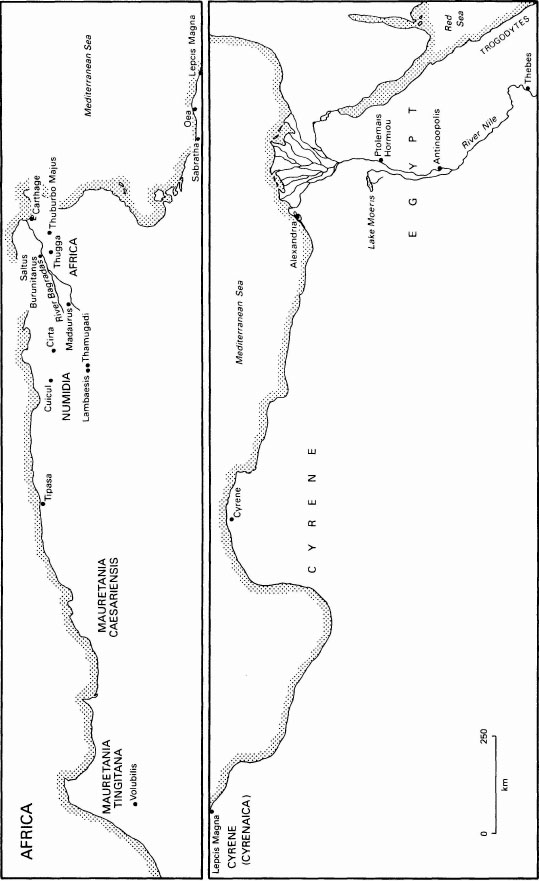

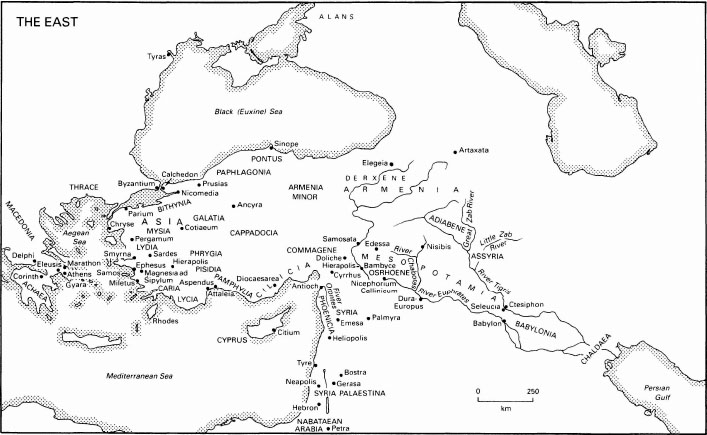

The Roman Empire was a startling achievement, partly because of its size. It was enormous, extending from the Atlantic to the Euphrates and from the Rhine and Danube to the Sahara. It is therefore of relevance and interest to those people of today who are thinking of rising above and beyond small national frontiers to multi-national unities, such as Europe and the other endeavours of a similar kind. For it has been done before: the Romans did it, and on a scale which has never been equalled since their day and will never be equalled again. The question of how well this gigantic empire worked is a matter of concern to those who are attempting, at least in part, to repeat the pattern today, at least as far as Europe is concerned ().

In the development of that empire the Antonines played a crucial part. By the Antonines I mean three successive emperors of the second century AD, Antoninus Pius (13861), Marcus Aurelius (16180); until 169 his colleague was Lucius Verus), and Commodus (180192). It was they who controlled this huge machine during more than half a century of its most testing period. They were not, of course, the first Roman emperors. Augustus (30BC-AD 14) had converted the Republic into an empire ruled by one man, known as the Principate, and he had been followed by four more emperors descended from or related to him, known as the rulers of the Julio-Claudian house (AD 1469). Then, after a period of civil war, followed the Flavian dynasty founded by Vespasian (6979) and continued by his two sons, Titus and Domitian (7996). Next came a series of rulers often known as the adoptive emperors because, having no sons around, they promoted the most meritorious successors they could find: the ageing Nerva, the popular, imperialistic Trajan, and the brilliant, controversial, widely travelled Hadrian (96138).

The eighteenth-century historian Edward Gibbon observed that the epoch of the Antonines, the second century AD, was the happiest period the world had ever known. This statement needs reexamination (the upper class: the other social classes of the Roman empire enjoyed a far from happy existence. On the other hand it can well be argued that in subsequent centuries today for example the lot of the unprivileged has not been any more satisfactory. Certainly in Western Europe and the United States there exist distinctly unprivileged and depressed groups, but they are not as numerous, proportionately, as those that existed in the Roman empire. Yet in the world as a whole an enormously large proportion of the population lives below subsistence level certainly a proportion large enough to give credence to Gibbons assertion.

On the other hand it must also be conceded that Gibbon was referring only to the Roman empire, and not to the vast areas of the world that lay outside it about which he did not know or care. So his statement that the Antonine world was unequalled for happiness must be considered in that light. Nevertheless, his assertion must be given due weight. The Antonine period did achieve something for its people, and something substantial. It was founded on the famous Roman Peace, which had never before been so complete and far-reaching, and never would be again: an achievement which is well worth looking at afresh, in this troubled late twentieth century in which hopes for universal peace have seemed within our reach (after the collapse of the Soviet empire) and then been dashed.

No one, as far as I know at least in recent years or decades has attempted to describe the reign of Antoninus Pius. It has been regarded as a model reign of peace and good administration, and he has been regarded as a model ruler: the man who worked so hard and so conscientiously that he trained himself only to go sparingly to the bathroom. But there are certain points that need to be studied once more. Why, for example, did he leave his heritage jointly to two men, one of whom was obviously unfit for it? And, most serious of all, is it true that this long period of peace and tranquillity concealed within itself the seeds of future decay the origins of the decline and fall of the Roman empire? Here is a matter of significance which we ought to investigate.

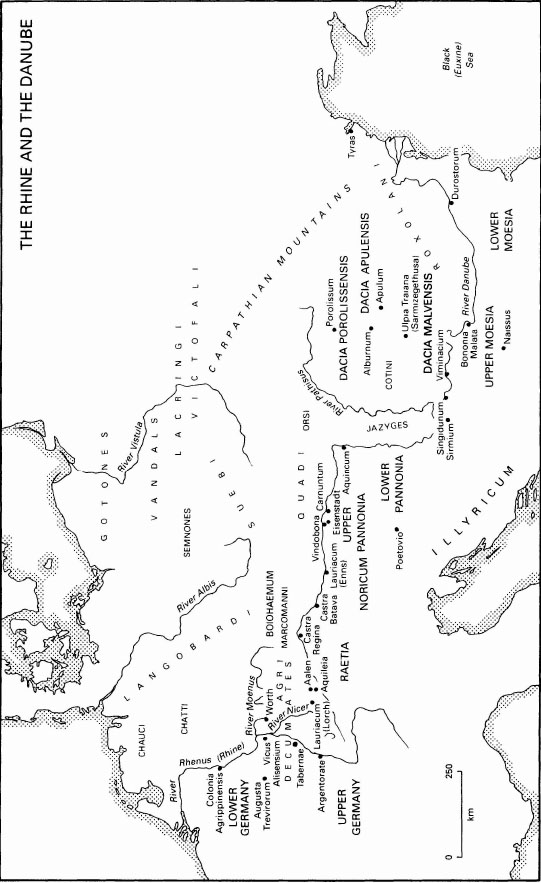

As to Marcus Aurelius, saintly man though in many ways he seems to have been, he had his personal problems: his reputedly unworthy colleague Lucius Verus and his allegedly immoral wife Faustina the younger. And it is interesting to note how he dealt with those problems. But the most striking of all of the difficulties that he encountered was the fact that this man of markedly intellectual and introspective tastes had to spend, or felt that he had to spend, such a very large part of his reign in military camps on the Danube, commanding Roman armies. This did not stop him from writing his Meditations, and it is to this astonishing work that I would particularly direct attention. The Meditations perhaps seem less remarkable than they should because they so often appeared in Victorian editions, bound in soft leather; and they have been far too rarely republished or looked at since then. This ought to be rectified. The work needs to be examined with great care, because it is one of the most acute and sophisticated pieces of ancient thinking that exists. It is also, incidentally, the best book every written by a major ruler.

Marcus Aurelius has often been blamed for abandoning the theory that the empire ought to go to the best man, by adoption, seeing that he instead nominated his own son Commodus as his successor: and Commodus proved a disaster. That Commodus turned out to be so disastrous, and effectively put an end to the blessings of the Antonine monarchy, can scarcely be contradicted. But that does not excuse the fact that far too little attention has been devoted to his biography and his reign. Here I would single out only two matters that seem to need careful reconsideration. The first is Germany. Three attempts were set in motion, in ancient times, to place Germany within the boundaries of the Roman empire, which would then have a shorter Elbe-Danube frontier than the long, right-angled Rhine-Danube frontier which actually existed. The first attempt was made, by Augustus, from the west: it collapsed catastrophically in AD 9, when Varus was ambushed by Arminius in the Teutoburg Forest. The second attempt was made by Germanicus, very soon afterwards, but is hardly worth mentioning because it was called off by his uncle Tiberius. The third attempt was launched by Marcus Aurelius, who intended to occupy Germany from the south, by way of the Czech Republic and Slovakia. When Aurelius died, the plan was immediately abandoned by his son Commodus, who acting perhaps on the suggestion of a Greek adviser returned to Rome instead. For this he was fiercely criticized by ancient imperial writers, and the criticisms have persisted to this day. But was he right or wrong? It would certainly have been satisfactory if Germany had been brought within the Roman empire, and it is possible to conjecture that such a step might have not only prevented or postponed its fifth-century Fall but also saved us from the two World Wars of the present century. But could Rome have afforded the hugely increased military expenditure and, for that matter, could the number of men in the army have been raised to an adequate strength? These are points which, as far as I know, have not been sufficiently considered, and I propose to do just that before pronouncing a verdict on Commodus.