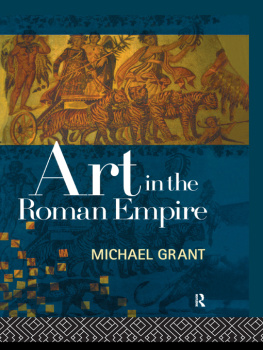

First published 1996

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada

by Routledge

270 Madison Ave, New York NY 10016

Transferred to Digital Printing 2011

1996 Michael Grant Publications Ltd

Phototypeset in Garamond by Intype London Ltd

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data

Grant, Michael.

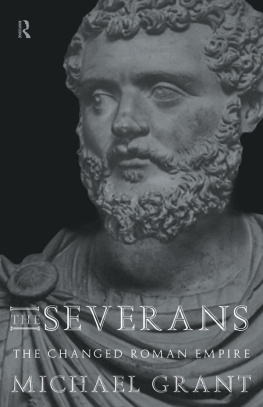

The Severans: the changed Roman empire/Michael Grant.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. RomeHistorySeverans, 193235. I. Title.

DG298.G73 1996

937.07dc20 95-45816

ISBN10: 0-415-12772-6 (hbk)

ISBN10: 0-415-62015-5 (Pbk)

ISBN13: 978-0-415-12772-1 (hbk)

ISBN13: 978-0-415-62015-4 (Pbk)

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original may be apparent.

The end of the Antonine period in AD 192 marked what could be called the termination of the high-water mark of the Roman empire. It has always seemed strange to many that Marcus Aurelius (161-80), a clever man, should have been so besotted by the dynastic, paternal principle that he left the empire to his inadequate son Commodus (180-92). But the murder of Commodus not only marked the conclusion of the Antonine house, properly so-called, but ushered in a period of civil war and imperial chaos, marked by a number of short-lived reigns and attempted reigns.

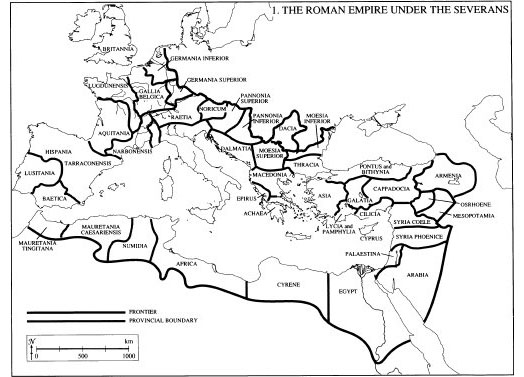

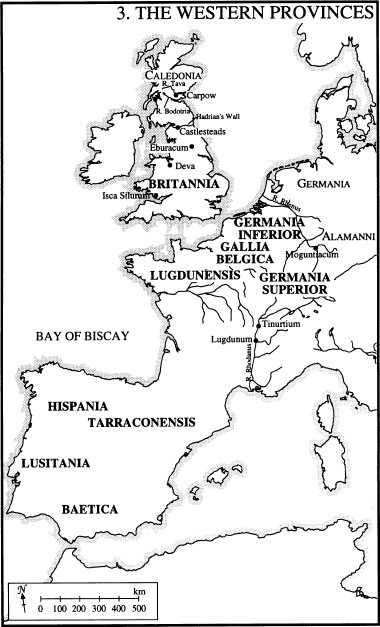

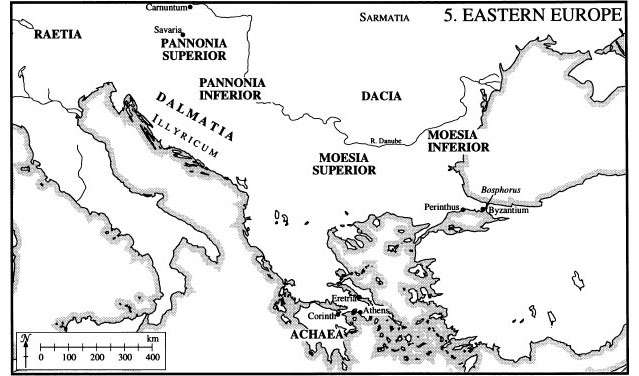

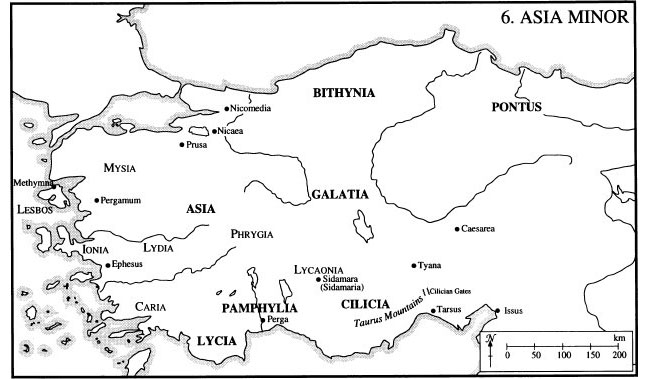

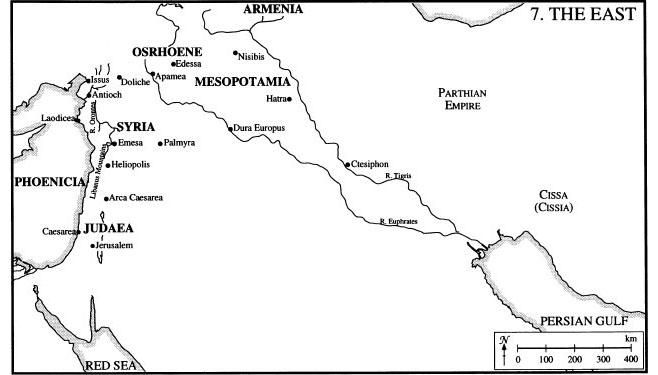

The first of these rgimes was that of Commoduss immediate successor Pertinax, emperor from January to March 193 (Plate 1). His father was a freed slave, Helvius Successus, who allegedly named his son Pertinax to celebrate his own perseverance in the timber trade. Mter a spell as a school-teacher, the future emperor Pertinax joined the army, rising to the command of units in Syria, Britain and Moesia. Then, following civilian posts (procuratorships of knightly (equestrian) rank in Italy and Dacia), he commanded legionary groups in Pannonia, where he fought against the Germans, subsequently becoming a legionary commander in Raetia, consul in 174 or 175, and then governor of Upper and Lower Moesia (combined) and Dacia and Syria, and subsequently commander of (mutinous) troops in Britain, proconsul of Africa and city prefect of Rome. In 192 he became consul for a second time.

This is a coin of Pertinax, who reigned very briefly in 193, and failed to replace the excesses of his predecessor Commodus by a regime of austerity. (But Septimius Severns, when he came to the throne in the same year, started his reign by posing as the heir and avenger of Pertinax, whom he deified and whose name he adopted.) The radiate crown on the coin indicates that it is a dupondius and not one of the asses, on which this sort of crown does not appear.

) invited Pertinax to accept the throne, whereupon he hastened to the praetorian camp, and promised the guardsmen a substantial donative, so that they duly acclaimed him as emperor. Then he visited the senate, which was obliged to concur.

But Pertinax soon became unpopular owing to a policy off inancial entrenchment, necessitated by Commoduss extravagance. In particular, he lost the support of the praetorian guard, since he had failed to pay them more than 50 per cent of the donatives he had promised them. So they murdered him, apparently on 28 March 193.

His successor was Didius Julianus, who reigned from late March until June 193 (Plate 2). Marcus Didius Severus Julianus was the son of a man who belonged to one of the leading families of Mediolanum (Milan). His mother was a north African. Before becoming emperor, Didius Julianus had a lengthy and prominent public career. He commanded a legion at Moguntiacum (Mainz), was governor of Gallia Belgica in about 170, and became consul, with Pertinax, in 174 or 175. Then he was appointed, one after another, to the governorships of Dalmatia, Lower Germany, Bithynia-Pontus and Africa (189-90), where he succeeded Pertinax.

After becoming emperor by disgracefully purchasing the throne at an auction after the murder of Pertinax, he proved unable to confront Septimius Severns, who came down from the Danube with the legions stationed in that area. Didius Julianus was killed, and Septimius took his place.

*The gold denomination is the aureus, the silver (or, by the time of Septimius Severns, base silver or billon) denominations are the antoninianus (introduced by Caracalla and temporarily suspended by Severns Alexander), denarius, and (occasionally) quinarius, and the bronze denominations are the sestertius, dupond-ius, as and (rarely) semis. Originally the sestertius and dupondius had been made of brass, i.e. copper mixed with zinc (orichalcum), and the as and semis of copper. But by now the purity and distinctness of these metals had been eroded, and all were more or less of bronze, in which the zinc of the brass and red purity of the copper were replaced by tin and/or lead alloys (M. Grant, Roman ImperialMoney (London, 1954), pp. 240f) . The bronze provincial and local coinages of the east had denominations of their own, mainly Greek.

After the latters accession to the throne, followed soon afterwards by his death, Didius Julianus made his own bid for the empire, which has gone down in history as a disgraceful episode. In successful competition with Titus Flavius Sulpicianus, the father-in-law of the late Pertinax and prefect of the city, Didius Julianus bought the job of emperor by offering the praetorian guard 25,000