Fonthill Media Limited

Fonthill Media LLC

www.fonthillmedia.com

First published in the United Kingdom and the United States of America 2014

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data:

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Copyright Paul Elliott 2014

ISBN 978-1-78155-334-3

The right of Paul Elliott to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission in writing from Fonthill Media Limited

Typeset in 10pt on 13pt Sabon LT Std

Printed and bound in England

Contents

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank a number of people who have offered photographs, advice or commentary on the book or who helped develop some of the ideas within it. These include Dr Robert Mason from the Royal Ontario Museum (which houses some of the Dura Europus collection), Alexandra Croom of the Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums, Dr Mike Bishop with whom I discussed the survival of lorica segmentata into the third century, Robert Vermaat who as always has been a ready source of good references and obscure papers, Dr Ross Cowan, Graham Sumner, Nathan Ross as well as Jamie McLean (with whom I toured Rome in 2012). Ten years ago Paul Carrick introduced me to Quinta, the third century re-enactment group based at Arbeia Roman Fort and Museum and I have never forgotten his help and generosity. Florian Himmler has likewise provided inspiration and advice in the field of third century reconstruction; several of the colour plates were generously provided by him. Megan Doyon of Yale Universitys Ancient Art Department skilfully organised copyright issues on my behalf surrounding photographs from the Dura collection. For location photography in North Wales I thank Graham Sumner.

My wife Christine deserves a mention. For twenty years she has accompanied me to hundreds of Roman sites throughout Britain, Egypt, Greece and Italy ... thank you!

Introduction

...things seemed hopeless and almost the whole Roman Empire had been lost,

Eutropius, Breviarium 9.9

The third century AD was a turbulent and testing time for the Roman Empire. A new and powerful foe in the east had risen up to challenge Rome directly. Barbarians on the northern frontiers were now more aggressive and more numerous than before and internally the population of the empire had to contend with rampant inflation and a series of terrible plagues. Pressure on Rome was now relentless and constant. Perhaps a single, capable ruler could have steered the empire on a safe course through these storms. Unfortunately, the chaos became magnified by a lack of continuity on the imperial throne. The army had become powerful enough that either it chose some pliant aristocrat to be emperor, or else one of its own tough soldiers (often of common origins) took control directly. Either way these emperors had no effective legitimacy and none could stay the course. From the assassination of Commodus (AD 192) to the accession of Diocletian (AD 284) the imperial throne saw thirty six occupants. Only four of those died from natural causes, the rest were either killed in battle, by the assassins hand or by suicide.

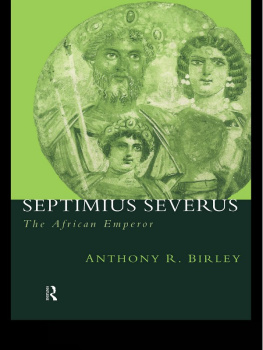

The army had real political power in the third century, making and unmaking emperors as it saw fit. It had been aided in this by Septimius Severus, the African emperor who had won out in the civil wars following Commodus assassination. He increased the armys pay and granted other privileges, he enlarged the Praetorian Guard, increased the number of legions and opened up command posts to men who were not of senatorial birth. Crucially Severus had promised a payment of gold to his troops if they supported his claim to the throne. This donative was so substantial that henceforth, troops knew full well that any rival for the throne who came from their ranks would reward loyalty with coin. And he knew how to cultivate loyalty. On his death-bed in AD 211, Severus gave his sons the advice they would need to stay in power: give money to the soldiers, and scorn all other men.

While the army gained rapidly in size, stature and political savvy during the reign of Septimius Severus, it also accelerated a material transformation. Armour, shields, helmets, swords and javelins all began to be replaced with new styles. A change in clothing altered the appearance of the typical legionary even further. By the end of the third century and the start of the authoritarian reign of Diocletian, the legionary had lost his familiar curved rectangular shield, no longer relied on the lorica segmentata or wielded the gladius (the short Roman stabbing sword). Neither did he wear a helmet that looked recognisably Roman. Yet these new-look Roman soldiers continued to dominate the battlefields of the empire for another two centuries.

Although emperor Severus did not kick-start this transformation, he presided over the empire just as the legions began to adopt both the new equipment and the new way of fighting. With his decision to enlarge and re-organise the legions Severus may have helped to spread the influence of this third century transformation.

Legions in Crisis looks closely at the new styles of arms and armour, comparing their construction, use and effectiveness to the more familiar types of Roman kit used by soldiers fighting the earlier Dacian and Marcomannic Wars. What did this transformation in military technology mean for the tactical choices used on the battlefield? A succession of emperors altered the organisation of the army piecemeal, reacting to immediate military threats to provide a flexibility that met the tremendous challenges of the age. We analyse the changes that Severus himself made and look at their impact on the Roman army as a whole. Did the higher levels of pay, the new conditions and the re-organisation also indicate a change of strategy?

The third century crisis certainly cried out for a new way of waging way. It seems that, in forts and on battlefields across the Roman Empire, the soldiers of Severus and their descendants were able to find the tools they needed to wage this war. Although the outcome had looked in doubt, the army and the empire it protected weathered the storm to emerge into the fourth century fully able to tackle the challenges of a new age.

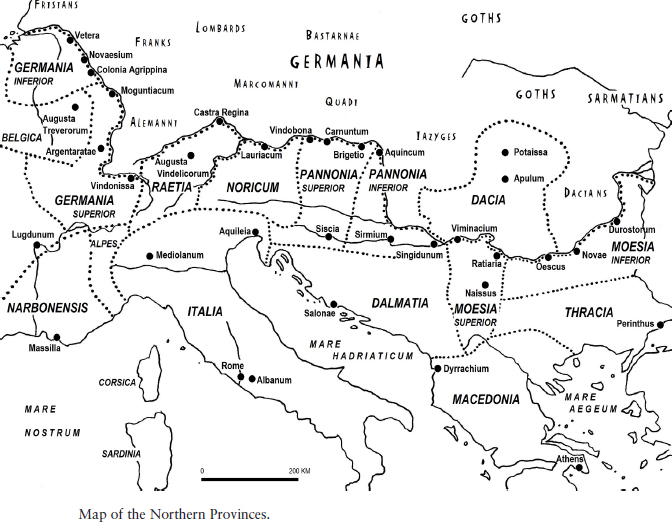

Map of the Northern Provinces.

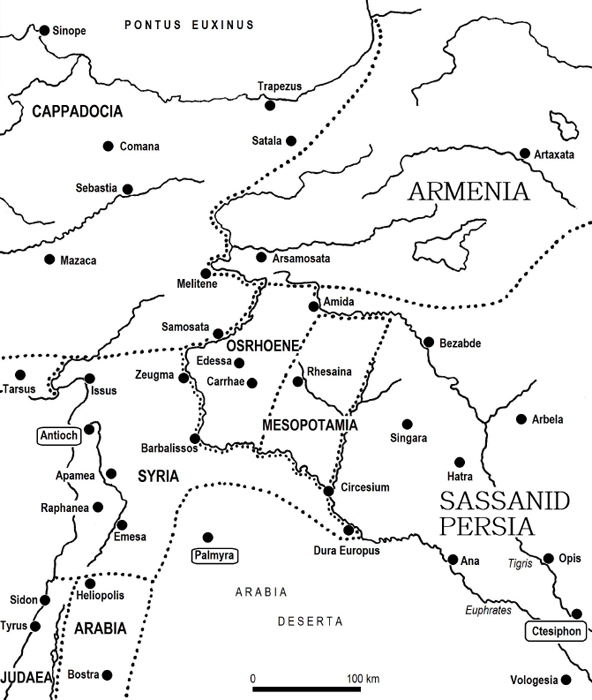

Map of the Eastern Provinces and the Frontier with Persia.

List of Emperors

This list covers the reigning emperors of the second and third centuries. Co-emperors who do not outlast their partner appear in parentheses.

Date (AD) Emperor

| 98117 | Trajan |

| 117138 | Hadrian |

| 138161 | Antoninus Pius |

| 161180 | Marcus Aurelius |

| 161169 | (Lucius Verus) |

| 180192 | Commodus |