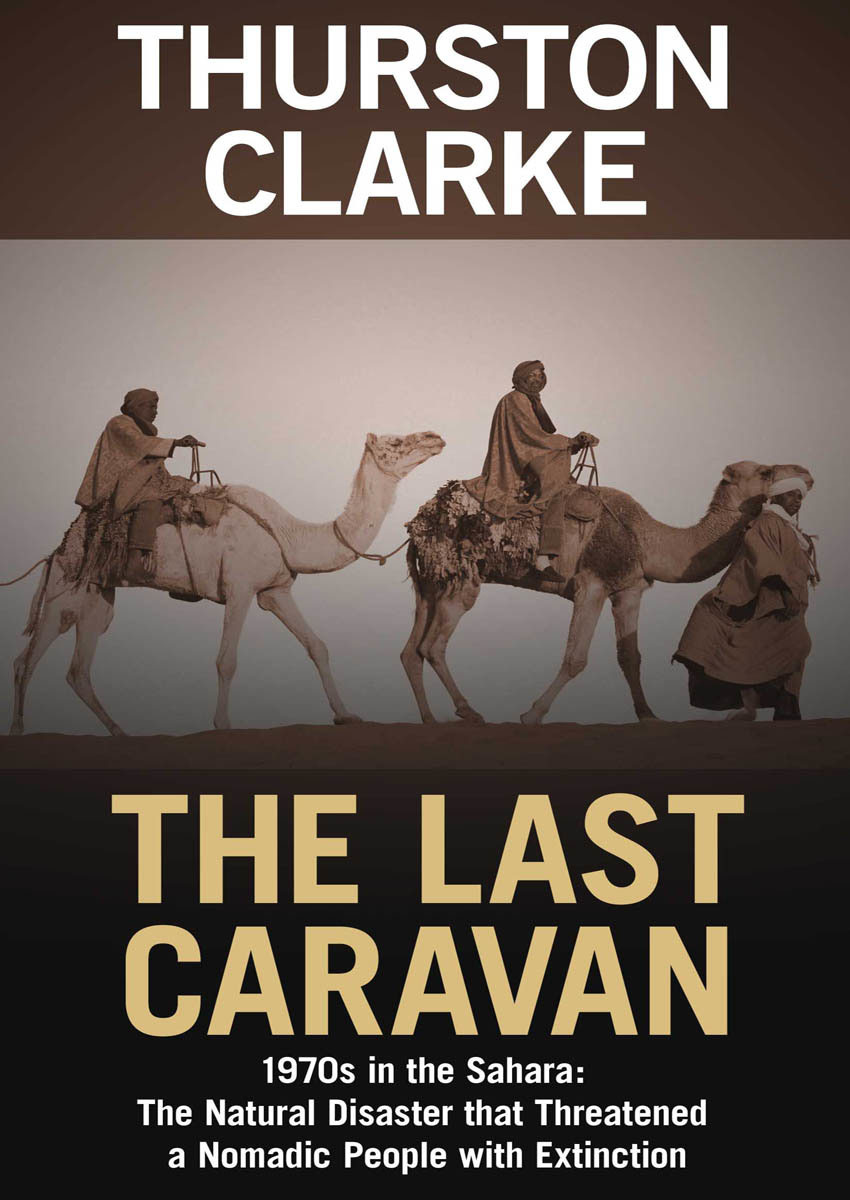

Thurston Clarke - The Last Caravan: 1970s in the Sahara: The Natural Disaster that Threatened a Nomadic People with Extinction

Here you can read online Thurston Clarke - The Last Caravan: 1970s in the Sahara: The Natural Disaster that Threatened a Nomadic People with Extinction full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Last Caravan: 1970s in the Sahara: The Natural Disaster that Threatened a Nomadic People with Extinction

- Author:

- Genre:

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Last Caravan: 1970s in the Sahara: The Natural Disaster that Threatened a Nomadic People with Extinction: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Last Caravan: 1970s in the Sahara: The Natural Disaster that Threatened a Nomadic People with Extinction" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Thurston Clarke: author's other books

Who wrote The Last Caravan: 1970s in the Sahara: The Natural Disaster that Threatened a Nomadic People with Extinction? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

The Last Caravan: 1970s in the Sahara: The Natural Disaster that Threatened a Nomadic People with Extinction — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Last Caravan: 1970s in the Sahara: The Natural Disaster that Threatened a Nomadic People with Extinction" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

1970s in the Sahara: The Natural Disaster that Threatened a Nomadic People with Extinction

Thurston Clarke

Also by Thurston Clarke

By Blood and Fire

Dirty Money

(with John J. Tigue, Jr.)

For my two fathersThurston and Esmond. And for the many friends who have supported meparticularly Carolyn, Marilyn, and Steven.

Between 1968 and 1974 a drought ravaged the people, animals, and land of the six countries that make up West Africas sahelian region.

The most serious years of this drought were the last two, from September 1972 to September 1974, when the cumulative effects of years of substandard rainfall resulted in a famine. During these two years the sahelian country of Niger endured the most devastating losses of crops and livestock.

Niger contains four major ethnic groups: the Hausa and Djerma farming peoples and the Peul and Tuareg nomads. All suffered during the drought, but because the Tuareg suffered and were transformed the most, I decided that they should be the subject of this book. In 1975 I went to Niger and interviewed individual Tuareg about their experiences.

Besides questioning Tuareg who had survived the drought, I visited most of the cities, towns, and nomadic areas in which the events described in this book took place. I went to In Waggeur, and on camel and on foot retraced the route followed by Atakor in the prologue. I went to Gao and visited the Mokhtar, Rissa, the animal market, and the portthe people and places described in chapter four. In Niamey, I arranged for the participants in the incidents described in the final chapter to re-enact their movements.

The people portrayed in this book are typical; the events factual. In some instances I have changed names and expanded individual stories with incidents that happened to other Tuareg from the same tribe or region during the same period of time.

Instead of assuming what people were thinking, I have decided to let them speak for themselves. Throughout the book I have consolidated their responses to my questions into longer statements.

Sympathy and aid for the victims of poverty and disaster in wealthy countries is often solicited by emphasizing individual tragedies. In poor countries, suffering is normally expressed in terms of mortality rates, health, diet, and life expectancy.

People become collages of gaunt faces pushing babies and empty bowls into the lens of a camera. It is easy to forget that these malnourished millions are comprised of unique peoples, whose struggle to survive is grounded in their own particular history and culture, and that these peoples are individuals, each drawing on his or her own genius, as well as that of their people, to wage a battle against extinction.

Atakor woke up nightblind. Flashes exploded in his eyes as he strained to adjust to the light of dawn. Usually they disappeared in a few seconds. Now they were prolonged by vitamin deficiencies.

He searched for his clothes. His feet swept the sand until they found his sandals. He lifted a blue robe, a boubou, over his head, strapped a sword to his waist, and hung red leather pouches around his neck. Sealed in each pouch were verses from the Koran. He patted them with the soft touch of the blind.

He pulled a swatch of indigo cloth through his right hand. The dark-blue dye that colored the material smudged his hands, and he then rubbed the blue residue onto his forehead and sunken cheeks. Previous applications had left a sediment in the lines in his face, making them dark and prominent.

The cloth was eighteen inches wide and twelve feet long. He draped it over his head like a shawl, the short left end hanging a foot below his chin, and gathered the remaining material in his right hand. He looped it once under his chin and wound the rest into a turban that covered his head. Then he drew the loop from under his chin over the bridge of his nose and pulled down a swath of the turban to shade his forehead like a visor. Veil and turban covered his face. Nightblind eyes stared through a medieval slit.

Never uncover your mouth in front of your wifes parents or Tuareg from other tribes. Before your own family or when you are among the blacks it is not necessary to be modest; you may expose your mouth. Twenty years ago a marabout, a member of a caste of Tuareg religious teachers, had recited these instructions as he wound the turban around Atakors head for the first time. Atakor had been fourteen.

During the last week hunger and sadness had drawn him into a fitful delirium. Time stopped, a past in which history had become myth and myth history slid into the present, and his exploits became confused with those of ancestors. The marabouts words came back to Atakor. He wore the veil, he thought, because Tuareg men had always worn it. It protected the face from the sun and the nose and throat from the sandy winds.

The women who sing, remember, and compose history had another explanation. Atakors wife Miriam recited a poem which claimed that once only Tuareg women wore veils. When a group of Tuareg warriors had been routed after a fierce battle and their camels seized, they straggled back to their camp on foot. Their wives had screamed, You have disgraced our eyes, vanquished warriors! In the future it is you who shall hide your faces! The women ripped off their veils and threw them at their husbands feet. The men had put them on.

Atakors taut, brown skin was visible only around his eyes. His mouth, his nose, the rest of his face were hidden. Clues to his emotions were found elsewhere. Frowns, smiles, scowls were reflected in his hollow hermits eyes, or in how he wrapped his veil: how tight, how close to the eyes, how high over the nose.

His movements revealed his feelings, and he had a repertory of shy, fluid, feminine gestures. With his thin arms and fine hands he smoothed his veil like a woman pulling the hem of her dress over her knees. Shaking hands, he followed the ritual of snapping his fingers and then touching his heart; when he served tea, he was like a geisha, pouring from a great height, arranging glasses in a neat pattern, smoothing and brushing the blanket for a guest.

These gestures were watched intently by others, and admired and criticized. On Nigers plains, the Taureg recognized each other from great distances by gait or a particular physical disability: A limp was a scar, a slouch a mole, a twitch a birthmark.

As he finished dressing, Atakors eyes registered the first strong light since he awoke. He walked east, toward it. One of his loose sandals slapped on the dry riverbed. He heard his wife stir, sigh, and gather her robes under the skin tent he had just left. His infant daughter cried. From a neighboring tent a tubercular cough answered.

He bent down, felt for his feet, and pulled off the sandal. He was too late. Miriam was awake.

Where are you going so early?

To save myself.

Not understanding, she swept the baby under her black cloak and comforted it. When mother and child were quiet, he went on his way.

The Tuareg call themselves the Kel Tamashek, the people who speak Tamashek. Tuareg is an Arabic word meaning the abandoned of God. Some linguistic authorities believe instead that the word refers to a particularly desolate place in the Sahara desert. In both cases the name has unwanted connotations, and the Tuareg themselves do not use it.

The Tuareg who live in Niger are accustomed to an annual hunger. The French who colonized Niger called this time of famine la soudure, the soldering. The image is of lips and fingers soldered together, of people unable to feed themselves.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Last Caravan: 1970s in the Sahara: The Natural Disaster that Threatened a Nomadic People with Extinction»

Look at similar books to The Last Caravan: 1970s in the Sahara: The Natural Disaster that Threatened a Nomadic People with Extinction. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Last Caravan: 1970s in the Sahara: The Natural Disaster that Threatened a Nomadic People with Extinction and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.