Ahmedabad Bangalore Bhopal Bhubaneswar Chennai Delhi Hyderabad Kolkata Lucknow Mumbai

P.O. Box 387, Dixon

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

| PREFACE |  |

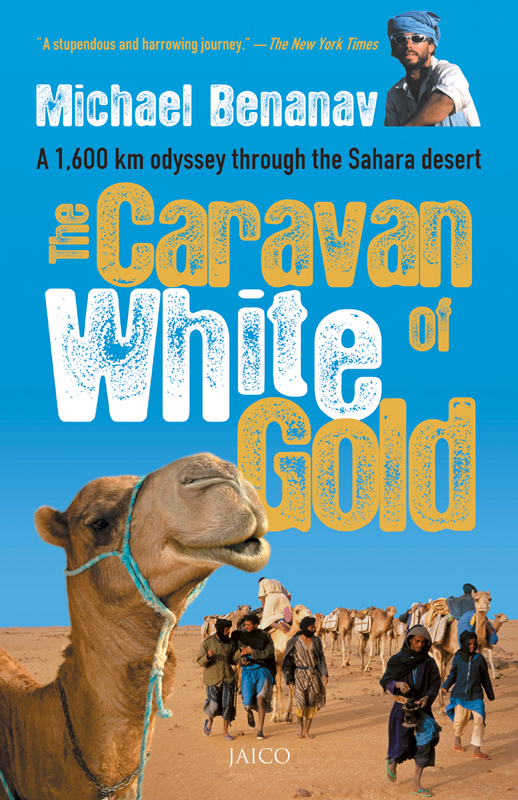

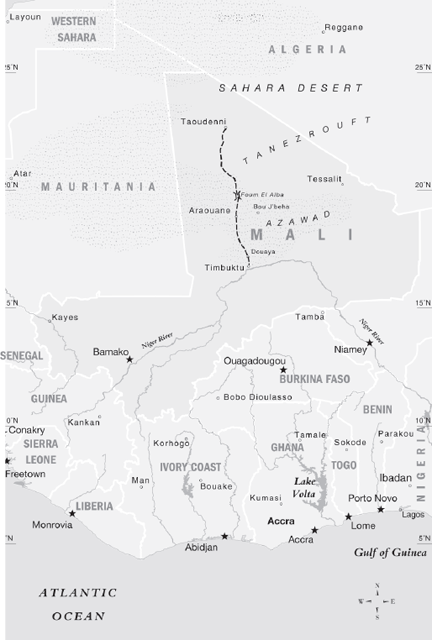

For the past thousand years, the Caravan of White Gold has plied the desolate sands of the Sahara. Its mission: to penetrate deep into the heart of the worlds largest desert and return to civilization bearing gleaming slabs of solid salt. Men clad in turbans, threadbare robes, and the occasional sports jacket lead strings of camels over some of the most severe terrain on earth, from the fabled city of Timbuktu (in the West African nation of Mali) to the remote salt-mining outpost of Taoudenni, nearly five hundred miles to the north, in the middle of nowhere. There they load their animals with tons of edible ore, then travel back across the desert to bring it to market. Their ancient, arduous way of life has hardly changed in the millennium since the salt caravans began.

Today these men and camels work one of the last of the caravan routes still active in the Sahara. The rest of the complex caravan network that once crisscrossed northern Africa has virtually vanished, victim to modern means of transportation; most goods, which in centuries past would have been carried across the great desert on camelback, are now flown over it, driven through it, or shipped around it by sea. Yet the Caravan of White Gold marches on, spared by its isolation.

The caravan route passes through one of the most notorious stretches in the Sahara, known as the Tanezrouftthe oldest and driest part of a desert bigger than the continental United States. Along the northern two-thirds of the trail, there are no human habitations or even nomad camps; the earth is simply too parched to support life. There are no oases, just a few solitary wells spaced days apart. Temperatures regularly surpass 120 degrees. Sandstorms sweep unchecked for hundreds of miles across the flat expanse. Entire caravans have left their bones there, including one time, in 1805, when some two thousand men and their camels arrived at a dry well and didnt make it to the next.

Taoudenni itself is in arguably the harshest spot in this harshest of regions. On an utterly barren plain hundreds of miles from the nearest village, miners hack tombstonesized blocks of rock salt from hand-dug pits using semiprimitive tools. Living in Stone Agestyle huts, they survive on a meager diet of rice, millet, and briny water; they have no medical facilities, no electricity, and no way of contacting the outside world but through those who travel back to it with salt.

Though Im a great lover of deserts, I had never heard of the Caravan of White Gold or the salt mines of Taoudenni until one night while I was surfing the Internet, researching the evolutionary advantages of one-humped versus two-humped camels in their respective environments. Having recently returned from a trip to Mongolia, home to the Bactrian camel, I wondered how its two humps could possibly serve it better than the single hump of its cousin, the Arabian, or dromedary. I eventually discovered that the Arabian evolved from the Bactrian, and had fused two humps into one for the same reason it had developed shorter hair, longer legs, and a leaner physiqueto keep its body temperature a few critical degrees cooler in the extreme deserts of the Middle East and Africa where it lives.

It was while following a divergent trail of camel-related web links that I stumbled across an article about the Caravan of White Gold. The caravan, the article asserted, was in its dying days, as trucks had recently begun competing for the salt trade. With their superior speed and carrying capacity, they would soon drive camels into obsolescence. It sounded like a Saharan John Henry story with a predictable endingthe death of the caravans and the iconic, age-old caravan culture. The noble ships of the desert, it seemed, were bound for dry dock.

As I read, my mind filled with exotic scenes of deserthardened nomads leading camel trains over a vast, undulating landscape. Enthralled, I read the piece again, my thoughts racing headlong into the Sahara. I hurriedly searched for more information on other websites, but was too excited to really focusnot because the caravans were doomed, but by the thought of joining one before they disappeared from the planet once and for all. Suddenly, my mental image of the caravans included me, galloping on camelback alongside the nomads, my head and face wrapped in coils of cloth like some archetypal Desert Man. I sensed that before long this vision would come true, even if I wouldnt ride as well as I had in my imagination. It was that feeling known by those of us who dont so much take journeys as are taken by journeys: hearing the call of a particular place for a particular purpose that will not be denied. And I was hooked. Too hyped up to sit at my computer any longer, I told myself it was the kind of trip I was born to take.

When I was nine, my father gave me an old hardbound biography called, simply, Lawrence of Arabia. I read it over and over, entranced by the deeds of a man who seemed to transcend the limitations of the possible, both culturally, by integrating with a fierce foreign people, and physically, by leading a band of underdogs to victory over the Turks and beating the British to Damascus. My desert traveling fantasies had been ignited.

In my twenties, I picked up Seven Pillars of Wisdom, Lawrences autobiography. After reading it, I made a pilgrimage of sorts to Wadi Rumm, in Jordan, partly to walk in Lawrences footsteps, mostly to see with my own eyes the stunning desert corridor that he described as a processional way greater than imagination.

Once there, I wandered alone for a week across salmoncolored dunes and among sandstone massifs intricately hewn and varnished by the elements. I spent time under the woolen tents of Bedouin families, drinking tea, talking Arabic, and eating fresh goat meat. Charmed by their hospitality, intrigued by their culture, I became hopelessly infected by a fascination with nomadic peoples.