Basically, youre going to be bloody cold.

ANTHONY CAZALET

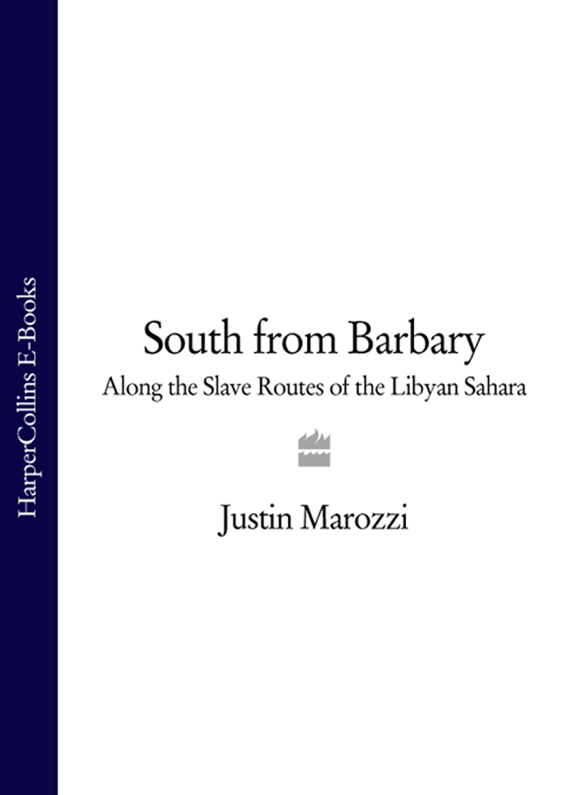

Help me with this camel, said Abd al Wahab, while Ned and I were busily applying Elizabeth Arden Visible Difference Eight Hour Cream to our faces. Abd al Wahab, our guide, understood camels. They were part of his world. Moisturizer was not. Hastily we packed it away, put the finishing touches to the last camel load, and marched off into the desert. We were under way.

For six years I had longed to make the journey we were now beginning. In a way I owed it to my father, for it was he who had taken me to Libya for the first time. Together, in the warmth of February, we had walked through Tripoli as the wind streamed in from the sea; past the forbidding castle, which had seen 1,000 years of wars and intrigues between marauding corsairs, pirates, Spaniards, Italians, Englishmen, Arabs and Turks, and still stared out impassively towards the southern shores of Sicily; through the ancient Suq al Mushir and into an exotic medley of sights, sounds and smells that roused the senses and stirred the imagination. Throngs of prodigiously built matrons haggled ferociously with softly spoken gold- and silversmiths for jewellery they could not afford. Some were still dressed in the same white, sheet-like farrashiyas their forebears had worn hundreds of years before. Others hid behind their gaudy hijabs (Islamic veils) as they sailed through the narrow alleys hunting for perfume. Deeper into the market, beneath a minaret from which the muaddin was calling the faithful to prayer in haunting, ululating cadences, we had found a dilapidated caf, its courtyard open to the sky, and taken our places alongside men playing cards and drinking mint tea, hunched protectively over their bubbling shisha pipes stuffed with apple-flavoured tobacco.

My fathers old friend Othman had taken us for a drive around the city in his Peugeot 504, a brave wreck of a car that had somehow survived several decades of neglect. In the squalid port area, men pored over slabs of tuna and disputed prices with the fishermen. One of these, a great hulk of a man, was tenderizing an octopus, throwing it to the ground, picking it up by its tentacles and then hurling it down again and again.

We call Tripoli ar Roz al Bahr, the Bride of the Sea, Othman told me as we drove past whitewashed houses along the old corniche, watched over by the palm trees that swayed in the coastal breeze. There was something unmistakably forlorn and beautiful about this city, a sense of wistfulness and a largely unspoken resentment. For centuries it had been a thriving commercial metropolis cosmopolitan, elegant and refined. Now there was nostalgia and regret in the peeling paint of the colonial Turkish and Italian mansions that, one by one, were being targeted for demolition as vainglorious symbols of the white intruders onto African soil. Thirty years of the revolutionary regime had almost brought the city to its knees cars fell apart, homes crumbled away, roads rotted and now sanctions held the city in a tight and unforgiving embrace. My father knew Tripoli well. He had got caught up in the 1969 revolution and had met the young Muammar al Gaddafi just as the old order of King Idris was being consigned to oblivion, but for me it was all new and instantly, wildly, romantic.

Before we left, my father took me to one of Tripolis few English-language bookshops, where I picked up the book that for the first time thrust the desert before me in all its guises. Here was silence and loneliness, the glory of wide African skies, unbroken plains of sand and rock, loyalty and companionship, adventure, treachery and betrayal. It was an account of the 181820 expedition into the Libyan Sahara led by Joseph Ritchie, a gentleman of great science and ability a diplomat, surgeon and friend of Keats tasked by the British government to reach and chart the River Niger from the north, one of the last remaining puzzles of African exploration. The enormity of his mission was not matched by corresponding resources and eight months after leaving Tripoli disguised as a Muslim convert, the penniless Ritchie had perished from fever in the insalubrious town of Murzuk, leaving his ebullient companion Lt George Francis Lyon to record their adventures for posterity. Back in London, reading his high-spirited tale, I felt the pull of the desert and started to dream of a similar journey by camel.

Like many ideas, it eventually faded away into a distant fantasy. Six years later, I was working in Manila for the Financial Times, when Ned, an old friend from school days, arrived unexpectedly. During lightning trips south to visit the jungle headquarters of the Moro Islamic Liberation Front rebels, and north to go duck shooting with a gun-toting provincial governor, we started discussing a longer expedition. I had spent almost two years in the Philippines and felt it was time to move on. Ned, a Dorset farmer, was feeling equally restless. We had travelled together several times over the years, from Hong Kong to Costa Rica, and knew and got on well enough with each other to attempt a more serious journey. Deep in the tropical jungle of Maguindanao I revived the long-dormant idea of crossing the Libyan Sahara by camel.

Ned would be the ideal companion. Solid and unflappable, with a keen sense of the absurd, he had travelled widely, was always ready for an adventure, and was practical in a way that I was not. Several years before, he had travelled across the Andes on horseback, and so was probably good with knots and would know what to do if a camel fell sick. At least, that was how I saw him. The truth was that neither of us knew the first thing about desert travel, but with some research in London and a reconnaissance trip to Libya much of our ignorance could be put right. The idea appealed to Ned at once. So much so that he wanted to know whether I was really serious about the expedition. I told him I was going with or without him. He said he was coming. Perhaps he felt the same lure of the desert. His great-uncle David Stirling, founder of the SAS, had fought in the Libyan Sahara during the Second World War, taking men like Wilfred Thesiger, the great desert explorer, on daring raids behind enemy lines.

From the jungle we returned to Manila where Joseph Estrada, the flamboyant former movie star, hard-drinking womanizer and self-confessed philanderer, had just been elected president in a landslide vote. The country looked as though it was heading back to the extravagant corruption of the Marcos era. Foreign investors cringed nervously on the sidelines, wondering if the currency would fall through the floor again. One by one, the Marcos cronies were welcomed back into the fold. The stock market was plummeting. Watching the rot set in again was depressing. See you in Libya, said Ned at the airport. My boss thought otherwise, but it was time to leave.