I feel that on three accounts I am at a disadvantage in the writing of this story. In the first place, the old question of truth crops up: nearly thirty others besides myself took part in our travels at various times, and were eyewitnesses of what I shall try to describe; most of them kept diaries, they all will read this book critically; some, I know, will go as far as checking dates and times. I can see one or two of the more meticulous of them throwing down the book in disgust were they to find even some innocent change of sequence, some elision of little happenings to make the account run better. How easy, in contrast, must be the literary task of the single traveller, with his unreading Arab retinue and his string of discreet camels. Not that I would for one moment hint that any of those illustrious solitaries has departed from the strict ungarnished truth by one sentence, say, of a native dialogue or by one phrase of the moons light in the description of that indescribable thing, a desert night. But what a temptation! Then, again, on all of the twenty thousand miles of journeyings each one of my companions looked out with different eyes and remembers with particular pleasure different scenes and incidents. They will all be disappointed that their pets have been left unmentioned.

The second difficulty is that we made a serious omission. We never had a thrilling disaster. We never lost our way, or broke down, with only a dried date to live on, till rescued by a harassed Authority after an exciting hunt with trackers and aeroplanes. We never went where we were not wanted, got shot up by angry tribesmen and provoked a reluctant government into sending out police and troops. In short, we had no news value whatever; a most discouraging state of affairs from which to extract material for a Book of Travel, where tragedy or averted tragedy is so great an asset.

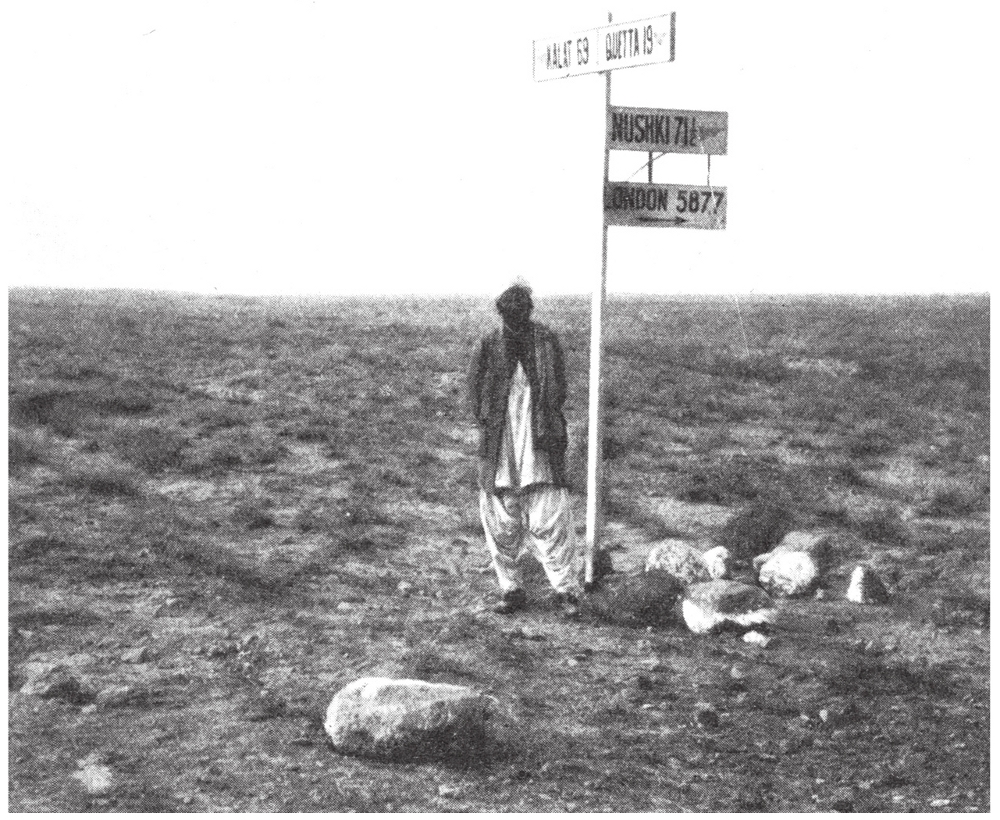

Lastly, we travelled by motor car. People condemn the motor car as unromantic. I am afraid this is natural, for no one can become fond of a thing he does not really understand, and the ordinary person understands a camel, if in concept only, because it is an animal like himself. But there is another prejudice against the motor car, especially on the part of the elder men who have done all their travelling before its advent. There is here a sense of sacrilege; the old difficulties and limitations that make the memories of their journeys so pleasant to them have been cheapened, the old thrill of achievement at the crossing of an Immensity is now, they feel, almost destroyed. But to us, who know not the old way, our memories are just as cherished. We have our own difficulties to surmount and we have our thrills. Even when we increased the scale of the possible far beyond camel range the desert is still big enough to remain Immensity.

The transition from camel to car is under way; it cannot be checked. But the passing of a romantic tradition is certainly sad. We can but console ourselves with the thought that it has all happened before that Roman travellers must have felt the same sense of sacrilege when the hideous camel was introduced to penetrate the sanctity of mysterious desert fastnesses, destroying all the romance of donkey journeys.

The history of the desert motor car in Egypt is oddly discontinuous. Introduced into the country early in the Great War by the British Army, it was found that the Ford car, even the Model T of twenty years ago, was capable of supplanting the camel in certain areas, notably in the Western Desert, and in 1916 a tiny force of light-car patrols, armed with machine guns, guarded the whole eight hundred-mile frontier against a possible recrudescence of the Senussi menace. These patrols covered great distances of unknown waterless and lifeless country as a normal routine, they took part in the final capture of Siwa Oasis from the Senussi, and among other things they succeeded in mapping, with the aid of speedometer readings and compass bearings, a great part of the northern desert, with its ranges of sand-dunes, between the Nile and Sewa. Their exploits, with the crude vehicles they had, were astonishing. The old tracks made by their unsuitable narrow tyres can be seen to this day, very faintly, far out even beyond the oases several hundred miles from the Nile. Sometimes one can see even their troubles; deeper ruts surrounded by vague old footmarks in the soft gravelly sand, where the cars stuck and had to be pushed out by hand. All this was a new thing, quite unknown in the history of deserts, or, indeed, of machinery. They evolved a lore of their own, so that their little patrols moved confidently about without much fear of disaster.

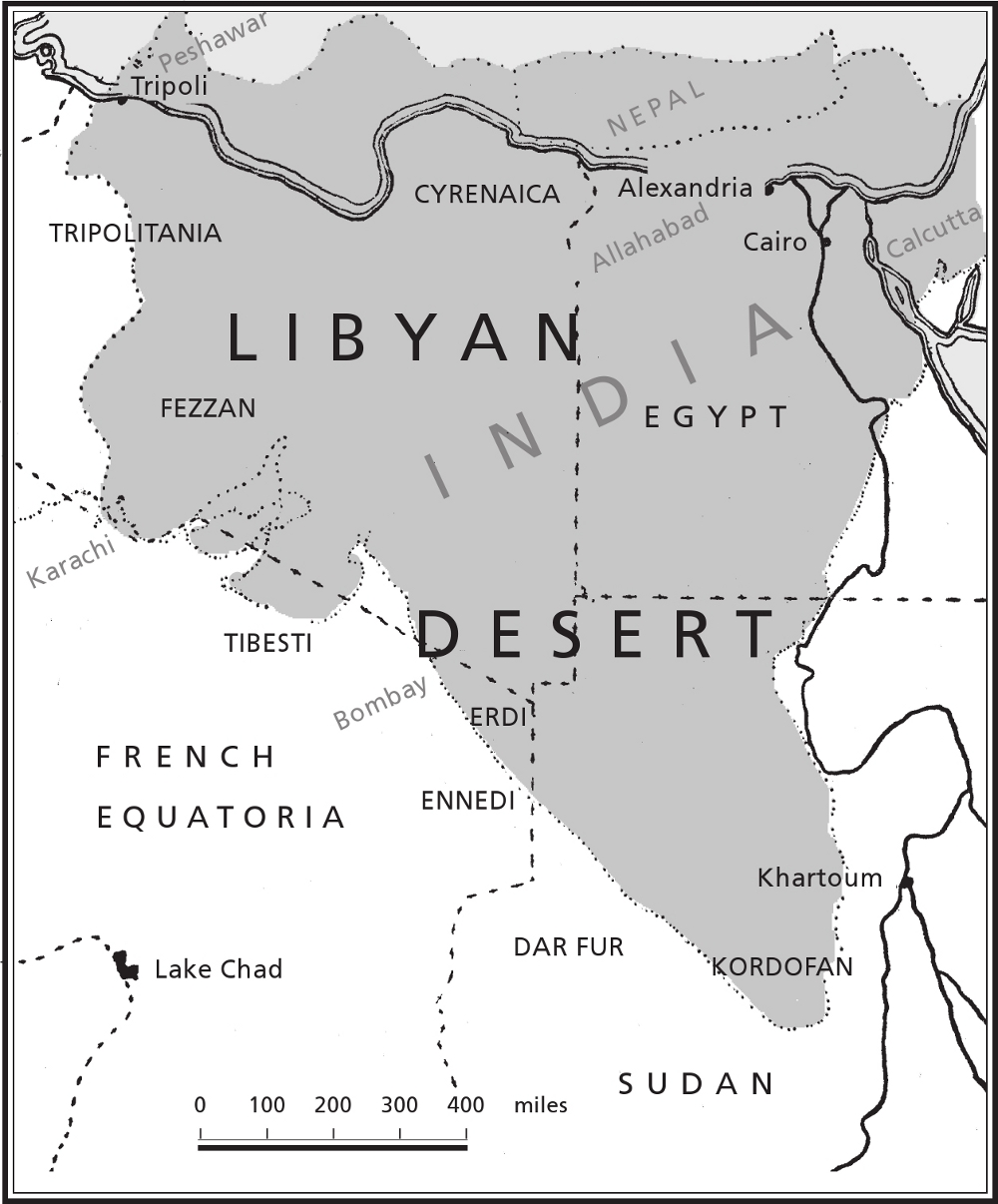

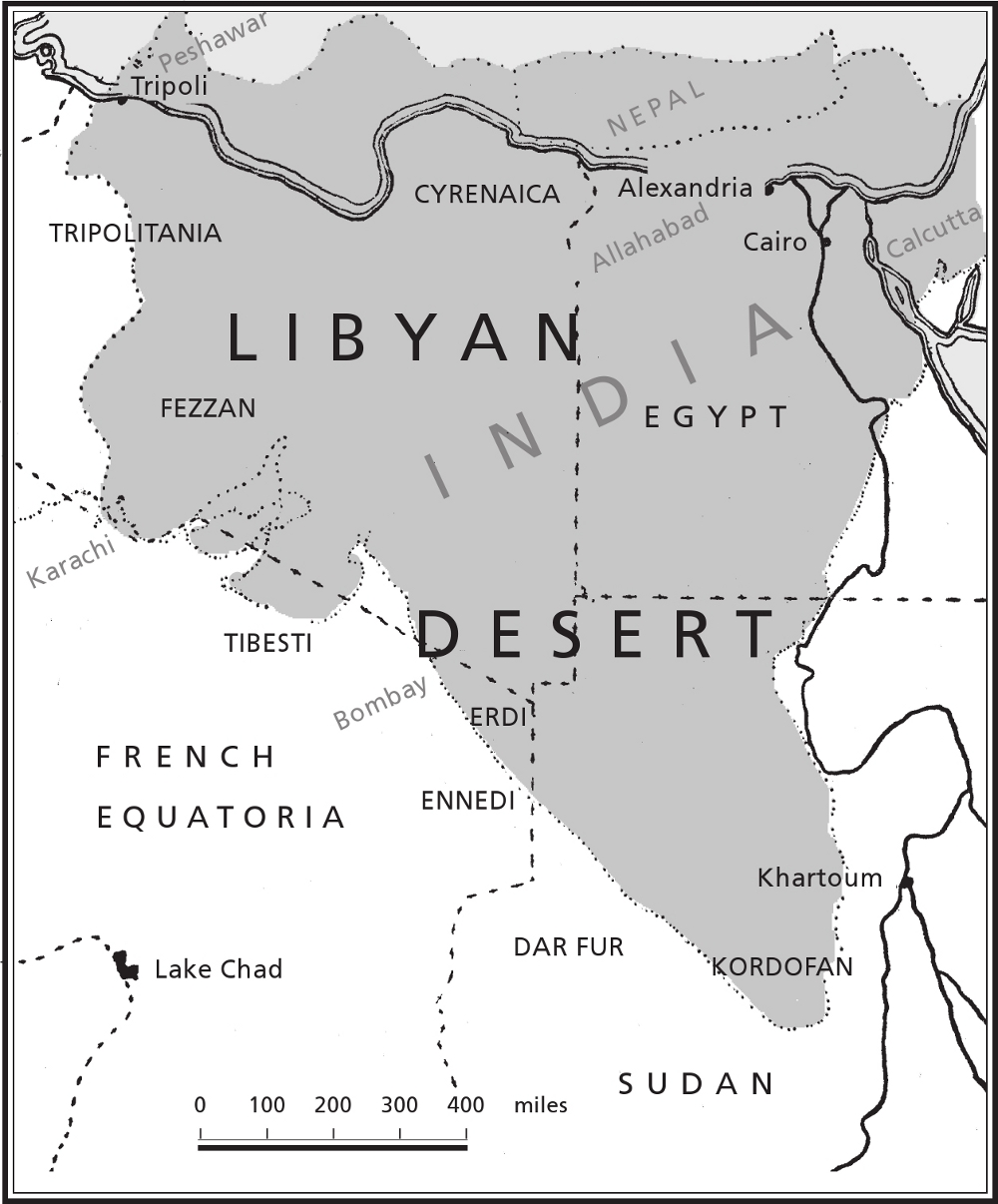

Libyan Desert with outline of India superimposed

In shape the Libyan Desert resembles the Indian peninsula, and, a fact which may be surprising but at the same time helpful, it compares with India in size.

Then came demobilisation. The light-car patrols were gradually disbanded, their personnel scattered to the ends of the world. Many of them appear, from the names they give to features on the map, to have been Australians. A few remaining cars were finally transferred to the newly-formed Frontier Districts Administration, or FDA, who used them largely for routine work along certain well-defined tracks which had been opened up during the war.

Official interest in the desert, away from these new car tracks, ceased with the war. The FDAs job was to administer the outlying human settlements on the very minimum allowance of public money, and no longer to patrol against marauding Senussi bands. The Senussi menace was over, and with it went the spirit of the light-car patrols, and most of the lore they had accumulated. All that remains are a few of the names of the pioneers perpetuated on the map in the names of certain of the nearer ranges of sand-dunes; even they are disappearing as the old native names are being discovered. As far as I can trace, no one has ever written up the history of the light-car patrols. It is a pity, for there was nothing like them before.

With the disappearance of the wartime army and the general reaction which followed the war, the opening up of desert tracks ceased completely. It was not until six years later that King Fouad revived the idea. Even in 1925, when I went out to Egypt for the first time, there was still no road to Suez. The old Overland Route built sixty years before, with its caravanseries and watchtowers, was in ruins. A Ford could just do it if there were enough people to push, and the eighty-mile journey took six hours or more. The famous Wire Road across the sands of Northern Sinai, by which the army had invaded Palestine, had disappeared. Even the method of its construction was forgotten. No one had driven a car all the way between Egypt and Palestine since the war ended, and when one car did get through in 1925 it was looked upon as a wonderful feat. So it was of enterprise in a country still tired of wartime over-enterprise on the part of the salesman who did it. All this but seven or eight years after a great army with all its vehicles and lorries had made the journey.