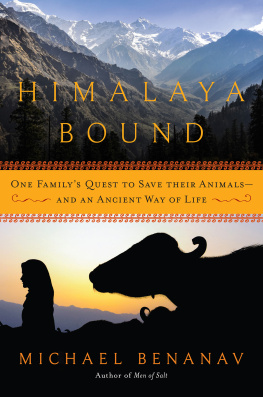

ADVANCE PRAISE FOR THE BOOK

Michael Benanavs portrait of the nomadic Van Gujjar people is compassionate, sensitive, and keenly attuned to the challenges confronted by traditional ways of life around the world. He shows how the modern conservation movement can inadvertently threaten ancient cultures, and he forces us to ask important questions about the relationship between man and nature in India today. Akash Kapur, author of

India BecomingThis book is not academic its a compelling adventure with the nomadic Van Gujjars, depicting their life with nature and their unique culture, as well as the encroachment by the state onto their age-old way of life. Medha PatkarThe world needs lessons in green lifestyles. Benanavs book tells us how nomadic and tribal communities lived rationally and frugally and built systems of survival to take only what they needed from the environmentIndias forests are habitats and we need coexistence and not war. Sunita NarainBenanavs account of a migration into the Himalayas by the Van Gujjars and their many buffalo is vivid, inspiring and touching in its portrayal of a people whose way of life is on the edge of extinction. Vanessa Able, author of

The NanolgouesClosely observed and sympathetically told, Benanav captures the very best of modern-day travel writingHalf-traveller, half-chronicler, Benanav serves as the very best of guides on this most unique of journeys. Oliver Balch, author of

India RisingCaptivating. Poignant. Inspiring. Benanav proffers an extraordinary insight into the lives of an age-old tribal culture and the multifarious challenges it faces in 21st-century India. Sarina Singh, coordinating author,

Lonely Planet Guidebook to IndiaAn easy and enchanting read,

Himalaya Bound is a great and important book providing insight into a vanishing way of life that is so important for Indias food security and biodiversity. Ilse Khler-Rollefson, author of

Camel Karma: Twenty Years Among Indias Camel Nomads In a one-room hut in the middle of the forest, Dhumman knelt and prayed, facing west, towards Mecca. Performing the ritual prostrations, his shadow rose and fell upon a mud-plastered wall that glowed in the flickering light cast by a crackling cook fire and a single kerosene lamp. His rhythmic chanting filled the hut with a low, resonant hum. It was two oclock in the morning.

Sitting on the dirt floor next to an earthen hearth, Dhummans twenty-two-year-old daughter watched the morning chai simmer while she was churning butter pulling back and forth on a rope that was wrapped around a wooden spindle, which sloshed vigorously in a narrow-mouthed pot filled with milk. Her teenaged brothers and sister, awakened by the demands of the day much earlier than usual, moved sluggishly around the hut, as though caught in the tendrils of lingering dreams. With their feet, they gently prodded their youngest siblings, who were still asleep on the floor. It was time to pack the bedrolls. It was time to get going.

The voice of their mother, Jamila, acted like a tonic, snapping her children out of their drowsy trance. At her request, the two eldest boys, flashlights in hand, left the hut to fetch the pack animals. Meanwhile, Jamila methodically placed the last of the familys belongings into saddlebags of thickly woven horsehair, which she then tied shut. When the young men returned, they carried the bags outside and loaded them onto the two horses and three bulls that they had parked by the door. Dhumman interrupted his prayers to issue instructions to his sons, reminding them to make sure that everything was properly balanced and well secured on the animals backs. The brothers, aged nineteen and sixteen, looked at each other and rolled their eyes; they knew perfectly well what they were doing.

In the darkness of the jungle, cowbells clanged, crickets chirped, and monkeys howled in the trees.

The mood in the hut was charged with the same kind of tension and excitement that families typically feel just before leaving on a trip. But there was nothing typical about the trip this family was about to take. Well aware of this, Dhumman closed his devotions by asking Allah to ease the difficult journey on which they were about to embark. Though he had travelled this route every spring since the year he was born, and was intimately familiar with the myriad challenges his family and their herd of buffaloes normally face on their annual migration, he had reason to fear that this year 2009 would be unusually tough.

Dhumman and his family belong to the Van Gujjar tribe and, like all Van Gujjars who are still able to practise their traditional way of life, they are nomadic water buffalo herders. They live year-round in the wilderness never in villages grazing their livestock on the vegetation that grows in the jungles and mountains of northern India. The tribe spends winters, from October to April, in the Shivalik Hills a low but rugged range that arcs through parts of Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand, and Himachal Pradesh. Amid the dense forest, each Van Gujjar family settles into a base camp; every day, from their huts of sticks and mud, they roam over gnarled sedimentary topography, through a tangle of deciduous trees and shrubs, feeding their buffaloes on the abundant foliage.

In the month of March, however, heat begins to sear the Shivaliks. By mid-April, temperatures soar to 45 degrees. The creeks that snake through the range run dry. As though baking in an oven, the forest canopy turns brown. Leaves wither, die, and fall from the trees. The once-verdant hills go bald. With little left for their buffaloes to eat or drink, the Van Gujjars must move elsewhere to survive. They pack their entire households onto horses and bulls and hike their herds up to the Himalayas, aiming for high alpine meadows that are flush with grass throughout the summer.

They stay in the mountains until autumn. Then, with temperatures plunging and snow beginning to fall, they retreat back down to the Shivaliks. By the time they reach there, usually in early October, they find the low hills bursting with life once again, the thick forest canopy regenerated over the previous months by the moisture delivered during the summer monsoon, the water sources recharged. With plenty to sustain their animals, they stay in the jungle each family often returning to the very same hut that they occupied the previous winter until springtime temperatures drive them back to the Himalayas. This migratory pattern up in spring and down in autumn has been practised by Van Gujjars in this part of India for many, many generations.

Its believed that the first Van Gujjars came to the Shivalik region, probably from Kashmir, some 1,500 years ago. No one knows exactly when or exactly why, but some in the tribe say their people were invited by the local raja; hed been travelling in Kashmir and was so impressed by the Van Gujjars, their buffalo herds, and the high quality of their milk, that he asked them to come live in his kingdom.