Contents

Page-list

Guide

Also by Anthony Sattin

Lifting the Veil: Two Centuries of Travellers,

Traders and Tourists in Egypt

Shooting the Breeze: A Novel

The Pharaohs Shadow: Travels in Ancient and Modern Egypt

The Gates of Africa: Death, Discovery and the Search for Timbuktu

A Winter on the Nile: Florence Nightingale, Gustave

Flaubert and the Temptations of Egypt

Young Lawrence: A Portrait of the Legend as a Young Man

Edited by Anthony Sattin

An Englishwoman in India: The Memoirs of Harriet Tytler

Florence Nightingale, Letters from Egypt: A Journey on the Nile

A House Somewhere: Tales of Life Abroad

Nomads

The Wanderers Who Shaped Our World

ANTHONY SATTIN

With illustrations by Sylvie Franquet

Text copyright 2022 by Anthony Sattin

Illustrations 2022 by Sylvie Franquet

First American Edition 2022

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact

W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Jacket design: Gregg Kulick

Jacket image: Leontura / DigitalVision Vectors / Getty Images

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

ISBN 978-1-324-03545-9

ISBN 978-1-324-03546-6 (ebk.)

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., 15 Carlisle Street, London W1D 3BS

For Sylvie, flneuse , who knows that not all those who wander are lost.

Contents

History, as nearly no one seems to know, is not merely something to be read. And it does not refer merely, or even principally, to the past. On the contrary, the great force of history comes from the fact that we carry it within us, are unconsciously controlled by it in many ways, and history is literally present in all that we do.

James Baldwin, The White Mans Guilt, Ebony , August 1965

Nomads: a subject that appeals to irrational instincts.

Bruce Chatwin to Tom Maschler, 24 February 1969

A young man walks towards me with a stick slung across his shoulders and a flock at his feet. The sheep, in front, beside and behind him, are as chaotic as meltwater in the nearby stream and they carry him down the path like a crowd of rowdy children. An older man follows, weatherworn but still strong, a rifle over his left shoulder. He clicks his tongue to encourage them forward. Behind him are two women on donkeys, one older than the other, and I guess they are his wife and daughter. They look strong women, but then it is a tough life beneath the shard peaks of the Zagros Mountains. Other donkeys carry their belongings, bundled inside heavy rust-and-brown cloth that the women have woven and will soon repurpose as door-flaps when the tents are set up.

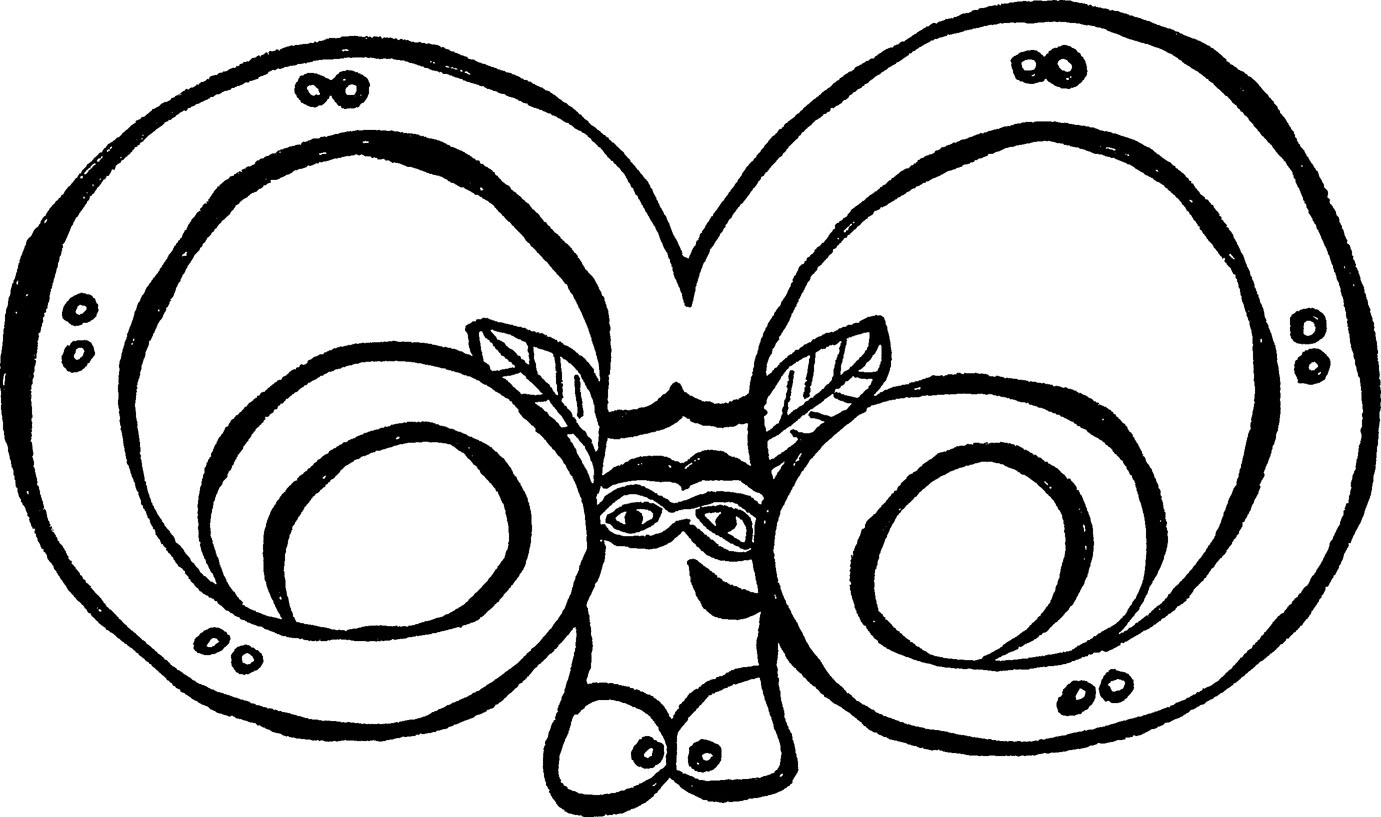

There are few trees at this altitude, but the snow has melted and there is intense beauty and excellent grazing in the valley blanketed with irises, dwarf tulips and other spring flowers. The family are smiling as they lead their sheep and grey-and-white goats along the rock-strewn track towards me, the bucks sporting majestic swept-back horns. And I am smiling with them, swept up by the excitement of the Bakhtiari tribes annual migration from the plains into the mountains in search of summer pasture.

I had already spent several days in the care of some other migrants. Siyavash and his family had pitched their black goat-hair tents on the slope of the valley, building an enclosure for their sheep and preparing a large open-sided tent to welcome neighbours and guests. My tent was across a stream flush with meltwater and from it I had a big view of the jagged snow-covered peaks and wildflower valley. A length of fat flattened oil-pipe served as a bridge between myself and the nomads and also as a reminder that the Middle Easts first oil strike, Well No. One, had been made in nearby Bakhtiari territory in 1908.

Everywhere there was beauty. If I were a photographer, I would have captured the shifting shadows and slanting sunbeams of afternoon as they tinted the snow mountains pink and cast gold across the surface of the stream. If I were a composer, I would have harmonised the rumble of water with the clunk of stones shifting across the riverbed, the buzzing of bees, the clanking of bells and the whistling and whooping of men bringing the flocks in for the night. There was beauty in all. But I am a writer and, barefoot and slightly sun-struck, I pulled out a pencil to note the pure quality of light in the blue sky, the way that colours, especially yellows, popped in the green valley and the sudden chill that descended as soon as the sun dropped behind the crest. Late that night, the nomads tents glowed like embers across the river, the moon shone full above the mountain ridge and I fell asleep wondering how Byron had known that Not vainly did the early Persian make/ His altar the high places and the peak... there to seek the Spirit... My spirits were soaring in that high place and I felt a deep welling of joy.

Over the next couple of days, Siyavash and his family introduced me to their valley and their people. They also fed me, and as we ate they talked about their lives, the land they knew, their journeys across it, the animals they raised, the children they worried about should they send them to a state boarding school for their education? and the many other challenges of being a herder in the Zagros Mountains in the twenty-first century. They told me about plants in the valley, the animals that passed wild above our heads and others that lived on the higher slopes. They knew all that could grow there, what to encourage, what to fear. They talked about the journey they had made from the hot lowlands into the mountains and how they would walk back again when the earth began to freeze beneath their feet, a journey their ancestors had made long before anyone began keeping records. I have heard similar stories from Bedouin and Berbers in North Africa and the Middle East, where I have spent much of my adult life, from Tuareg and Wodaabe beyond the mudhouses and libraries of Timbuktu, from swift young Maasai, flashes of orange across the red East African bush, from nomads on the edge of the Thar Desert in India, on boats in the Andaman Sea, in the uplands of Kyrgyzstan and elsewhere in Asia. Whether with Berber or Bedouin, gaucho or Moken, conversation always seemed to settle on the same issues, on continuity, on pride in belonging, on being in harmony with their surroundings, respecting all that nature offers and on the difficulties of living a nomadic life when governments wanted them to settle.

These people all reminded me of a sublime harmony that exists with the natural world. They knew their environment in a way that can only be acquired through living on equal footing with everything in that world, not in domination, through a recognition that we humans are dependent on our surroundings, something those of us who live in towns and cities too easily forget. The Bakhtiari know the significance of each tone of their herds bleating, when they are content, or hungry, or threatened, whether a birth or death is near, just as they know how to read the clouds, and the scents carried on the winds. The more I watched and listened, the more I was reminded that we had all lived this way once and not so very long ago, in the greater scheme of human things.