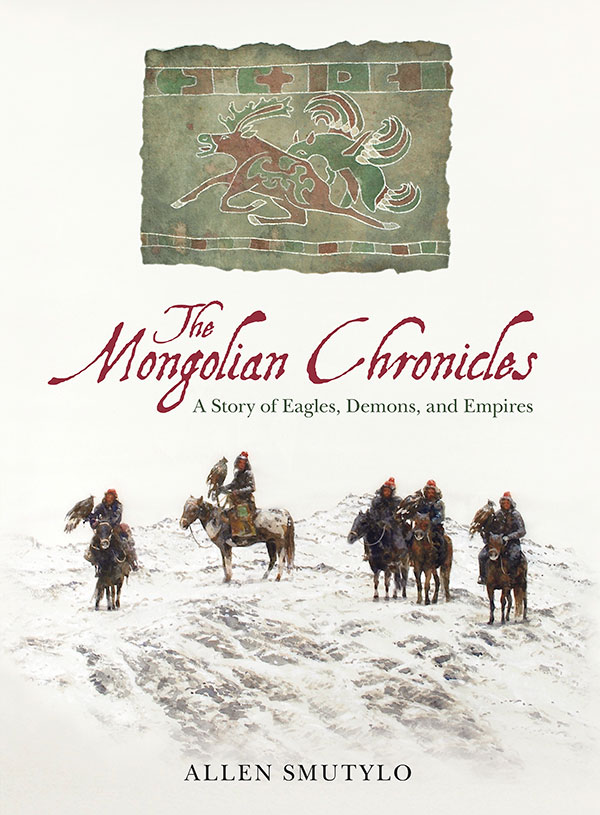

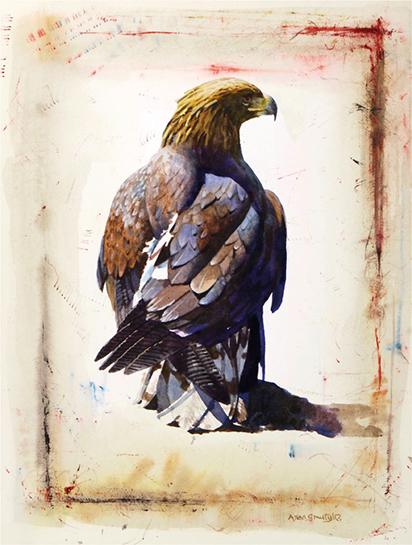

Compadres, 2018, watercolour, 12 x 21 inches

Ive spent most of my adult life going to remote places. What I find and experience there is what I try to convey through my artwork or writing, or both. Im regularly asked why or how I go about choosing a particular place. Apart from it being off the beaten track and/or having an interesting culture, Im not really sure.

I dont do a lot of pre-trip reading about a place that usually comes after. Discovering the unexpected is an important ingredient in my work, acting as a motivator: I want the surprise. A simple word or phrase often triggers the initial interest to go somewhere. Paddling with icebergs inspired the first of several expeditions to Greenland, even though I had never sea kayaked before. Or Nomads of the Himalaya; that is, bands of people living in tents, wandering around in one of the worlds most extreme environments. Or Funeral pyres on the Ganges one of the most sacred places on Earth, as well as one of the most fouled. The juxtaposition of the uncommon, combining extremes, seems to have an irresistible draw for me.

The allure of Mongolia falls into that category. It is a land of contradictions and extremes: parched and sun-scorched in summer and minus fifty and snowbound in winter. A capital city skyline profiles a hundred gleaming high-rises, intermixed with a ghetto of two hundred thousand canvas tents. A country dominated by vast tracts of virgin wilderness but with one of the most polluted cities on Earth. A citizenry that has developed an appetite for bistros, smart phones, and Western fashions but often looks to shamans for answers to lifes questions. An economy focused on voraciously gnawing out the nations natural resources, while above ground, nomads shepherd their sheep and goats to mountain slopes to graze on stunted grass.

As a place name, Mongolia resides somewhere deep in the corners of our human consciousness. Whether youve been there or not, its name carries a disquiet, like a wolf packs howl or the sound of rolling thunder or the cadence of a shamans drum. As a country and as a synonym it is associated with the ends of the Earth: wild, remote, mysterious, and threatening. But beyond that, my interest to journey there was activated by a single phrase: Eagle-hunting nomads.

In the shadow of the Altai Mountains, along Mongolias western border, is the isolated home of an ethnic people called Kazakhs. These hard-living nomads have survived on these windswept steppes, by their wits and with their animals, for millennia. Although the Kazakhs are mostly pastoralists, just as their forbears, they are also hunters of wild animals. It was sixteen years ago that I first heard of the extraordinary method they use to hunt their prey: not with dogs, or rifles, or bows and arrows, or leghold traps but on horseback with huge golden eagles. At first, I thought this must be something from the distant past or a wilderness legend, like the sasquatch elusively roaming the high Himalayas. When I discovered that it was in fact true, I added Mongolian eagle hunters to my need to see some day list.

That someday happened in the fall of 2016. As I prepared to leave for Mongolia, my focus was on eagle hunting only. This was the story I planned to depict in my artwork. And I wasnt disappointed: golden eagles on the arms of nomads on horseback, riding along snow-clad mountain ridges the visual wow factor was certainly there. But that singular emphasis changed, or at least widened. The door I opened into the world of eagle hunters lead not to a singular room but rather into a sizeable house, and its multiple rooms and levels revealed other themes and subjects that motivated my return to West Mongolia a year later.

...

The golden eagle, one of the largest raptors in the world, interested me all by itself. I knew these magnificent birds were not classified as endangered or even as rare, yet they were far from common. In all my travels, Id never spotted one. A friend who is a professional ornithologist assured me that a golden eagle sighting, at any time and any place, is especially noteworthy.

Ive learned that in the West, and in other places in the world, falconers have on rare occasions trained and used golden eagles, but most regard the bird as too difficult and dangerous to groom as a surrogate hunter. This eagle is a true recluse, steadfastly intolerant of sharing its habitat with people a fact that makes its relationship with Kazakh falconers all the more remarkable.

I also learned that in Western falconry an inordinate amount of patience is required to bond with and control any wild raptor. Taking on this sort of concentrated effort and daily expenditure of time demands some degree of financial security, or at least flexibility in ones work life. So I found it hard to fathom how Mongolian nomads, already leading a precarious existence, could accommodate such a time-consuming sport. That question was quickly answered in West Mongolia. I saw that the passion nomads had for their hunting eagles was infused into their culture and that their relationship with the sport went well beyond any monetary or time constraint. A couple of the older hunters confided to me that hunting with their eagles had long since veered from an enjoyable pastime to what they regarded as an addiction.