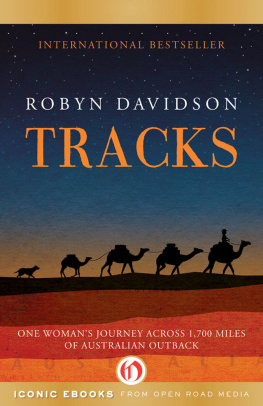

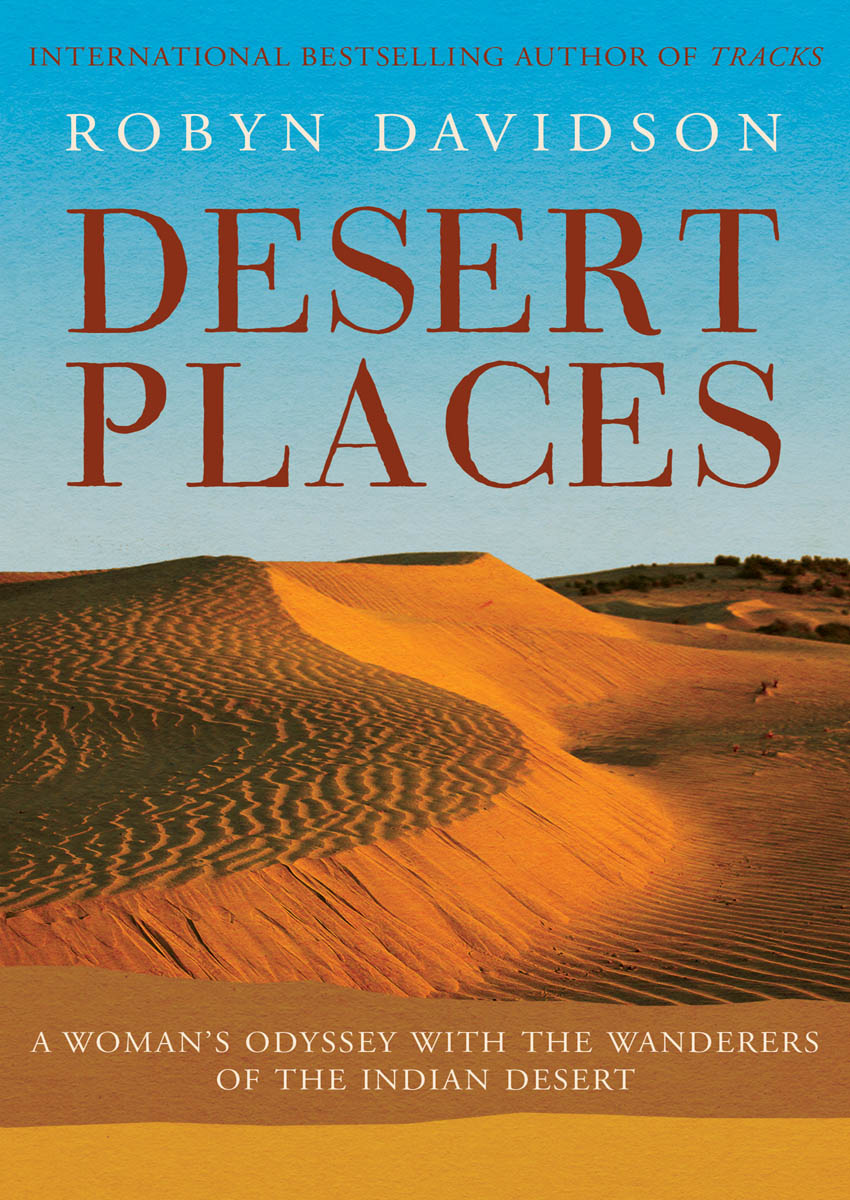

Desert Places

A Womans Odyssey with the Wanderers of the Indian Desert

Robyn Davidson

ROBYN DAVIDSON

FROM OPEN ROAD MEDIA

Find a full list of our authors and

titles at www.openroadmedia.com

FOLLOW US

@OpenRoadMedia

They cannot scare me with their empty spaces

Between stars on stars where no human race is.

I have it in me so much nearer home

To scare myself with my own desert places.

Robert Frost, Desert Places

Part One

False Starts

Prelude

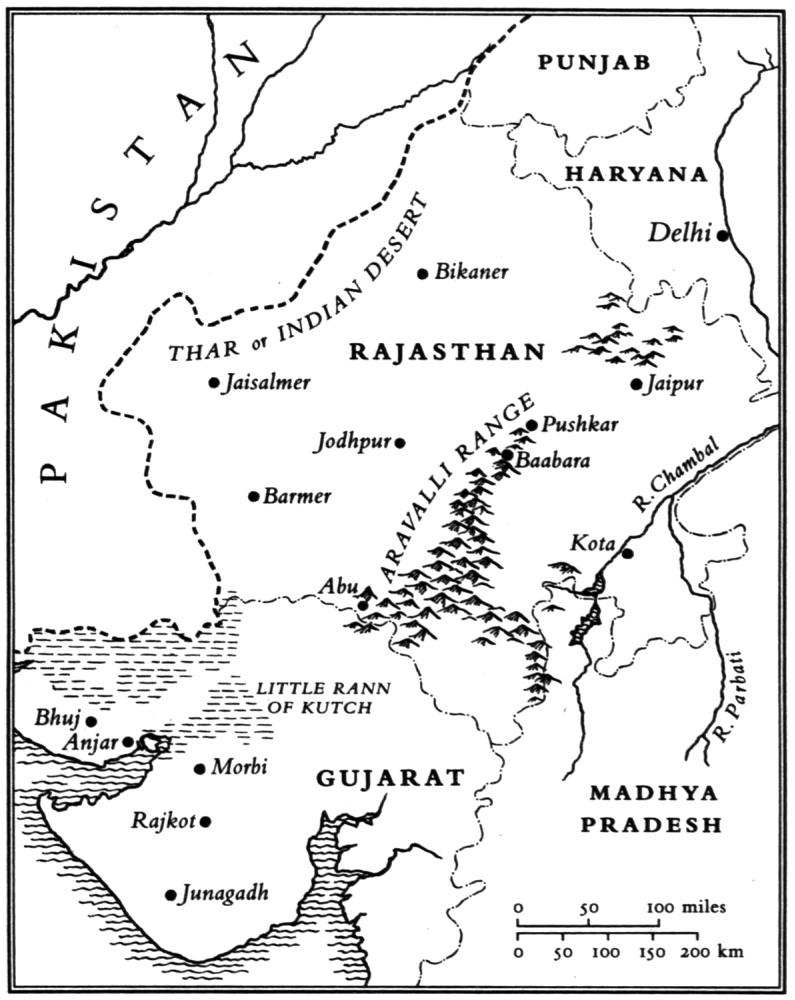

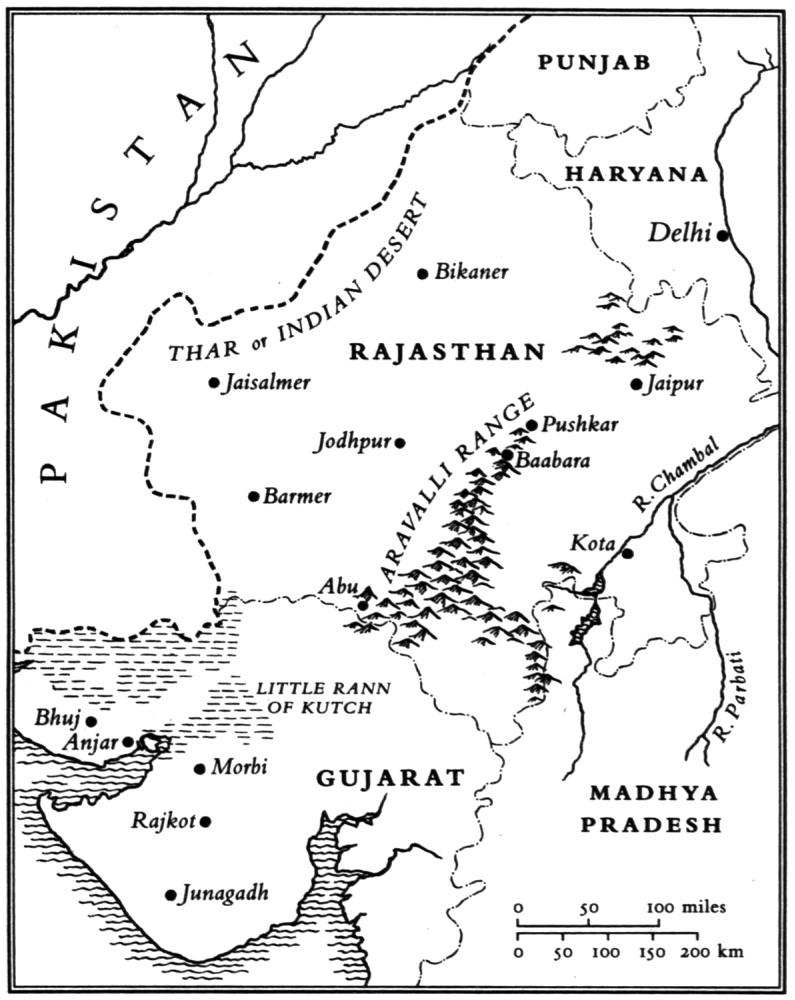

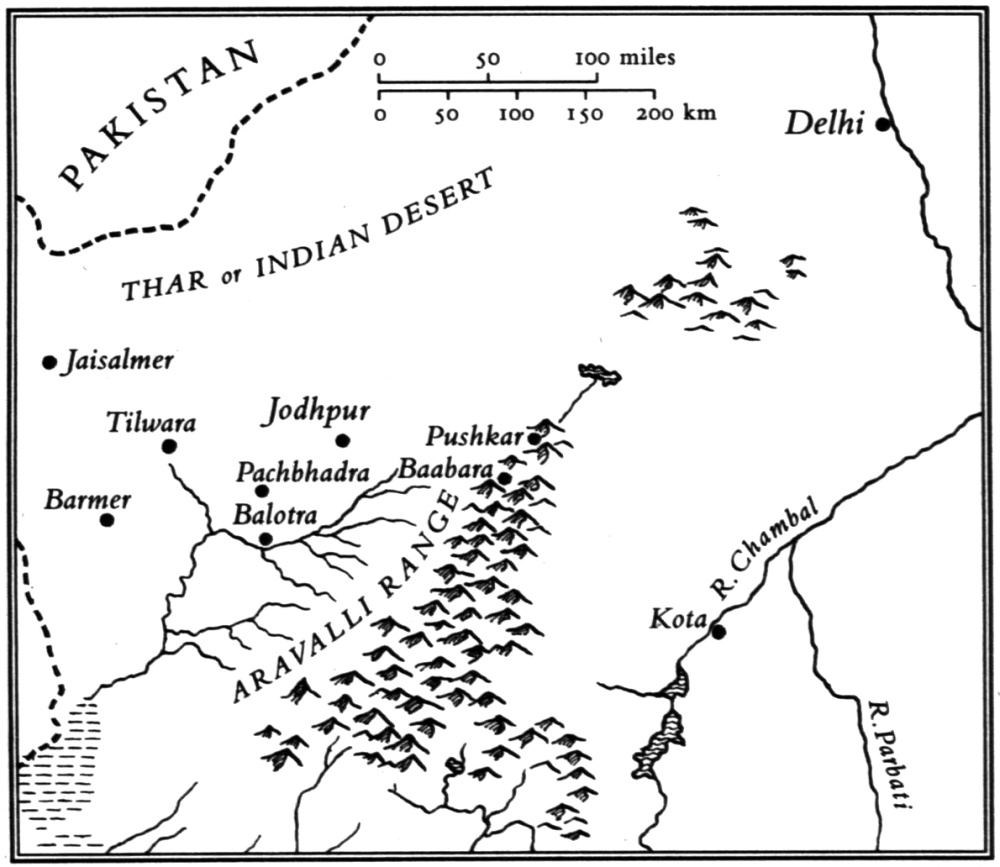

MEMORY IS A CAPRICIOUS thing. The India I visited in 1978 consists of images of doubtful authenticity held together in a ground of forgetfulness. I dont know how or why I ended up in the medieval lanes of Pushkar, in Rajasthan, during one of the most important festivals in the Hindu calendar. But Im almost sure I was the only European around.

The crowd was a deluge drowning individual will. It unmoored things from their meanings. Turbans and tinsel, cow horns lyre-shaped and painted blue, the fangs of a monkey, eyes thumbed with kohl looking into my own before bobbing under the torrent, a corner of something carved in stone, hands clutching a red veil, a dacoit playing an Arabian scale on his flute, his yards of moustache coiled in concentric circles on his cheeksall these elements sinking and reappearing, breaking and recombining, borne along by the will of the crowd in which a whirlpool was forming, sucking me to its centre.

A beggar was lying on his back. His legs were broken and folded, permanently, into his groin. He moved sideways along the lane, using the articulations of his spine, through garbage and faeces, drawing his flotsam along with him, rolling his eyes backwards in his head and muttering mantras, or perhaps nonsense. He wore a white dhoti and his body was whitened with ash. His turban was parrot green and I think I remember make-up on his face, though I may have painted it on afterwards. A parrot took coins from the tentacles of arms swirling above it and placed them in a bowl on its masters stomach. I breasted through the crowd, past the limbs of street sleepers jumbled in shadows, hindered by hands and imprecations, out at last to air.

You can walk for months in Australia without meeting a single human. Thousands of miles empty of footprints, unburdened by historys mistakes. Through an association with the original inhabitants I had learnt to see that wilderness as a gardenmans primordial home before the plough. The tracks of the ancestors mapped it and gave it meaning so that however far an individual might travel from the place of origin, in the deepest possible sense he or she was forever at home in the world. In Aboriginal society everyone received a share of goods and the only hierarchy was one based on accumulated knowledge to which everyone could aspire. The Australian desert and the hunter-gatherers who translated it had so informed my spirit that the crowds of Pushkar were unnatural and frightening to meevidence that agriculture had been my species greatest blunder.

Thousands of camels were tethered on hills surrounding the town. Nomads had come here from all over north India to buy and sell their animals. I climbed up to their encampments, away from the river of souls. When I reached the crest of the hill I turned to look back. A full moon had risen. The rumble of the crowd was muffled under a layer of pink dust. There was a sensation of suspension. All around me camels sat peacefully chewing the cud. Groups of men lounged back on the sand sharing chillums. A woman called me over to her fire. Her dress was a sunset of reds, pinks and silver. When she moved, ornaments rattled. A veil was draped over a contraption in her hair so that it peaked like a pixies hat. Had she pulled out a wand and offered me three wishes, I would not have found her more fantastic. She flung down a camel-hair mat, tugged me on to it and seemed to be asking if I would swap my necklace for her silver one. I tried to explain that hers would be more valuable than mine and, despite her entreaty to stay longer, wandered away.

But a wish was forming. It took the shape of an image. I was building a little cooking fire in the shelter of soft, pink dunes, far away from anything but a world of sand. It was twilight, the lyrical hour. The nomads were gathering beside me by the fire. There was fluency and lightness between us. We had walked a long way together. The image exalted the spirit with its spareness and its repose. My only excuse for having it is that I was young, and youth is vulnerable to Romantic sentiment.

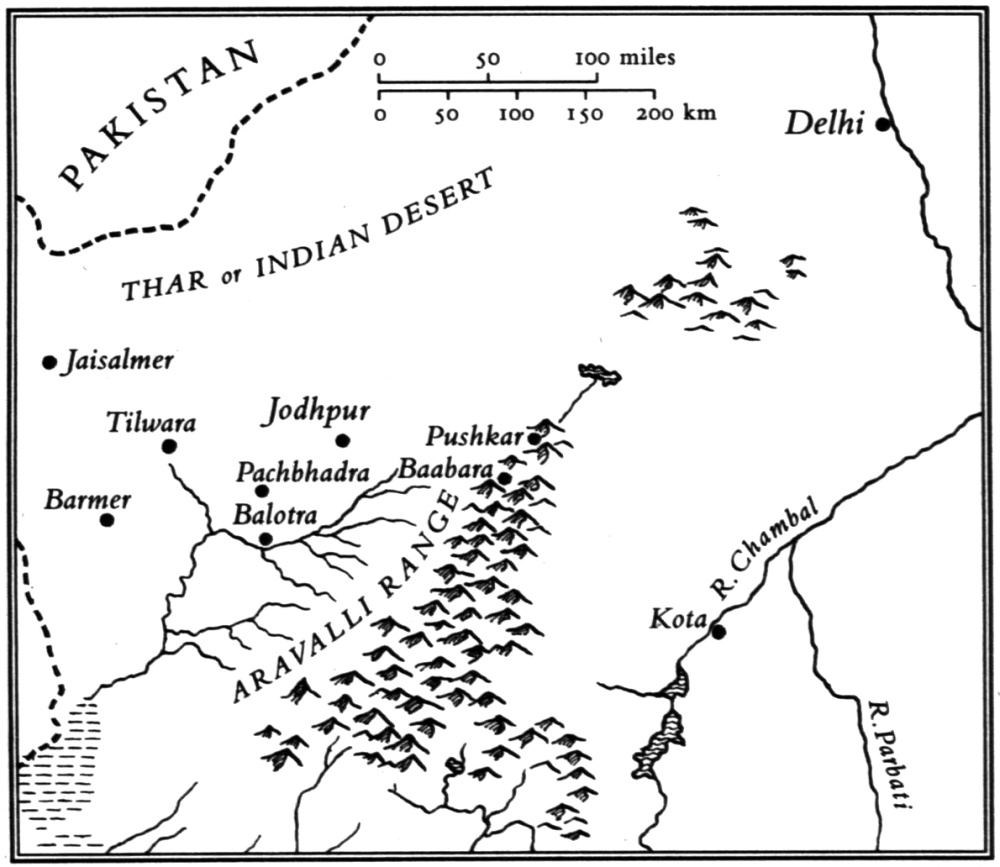

I made some inquiries. The nomads were called Raika or Rabari and they herded camels and sometimes sheep. There was a folklorist in Jodhpur who knew everything about them and would be happy to answer my queries but was busy entertaining a French journalist that week. I had eight days left in India. French journalist notwithstanding, I had to try my luck.

The only other European on the plane was a French woman. So when she went to shake hands with a personification of elegance dressed in black jodhpurs, black kurta, black sunglasses and black moustachewho, minus the sunglasses, might have stepped out of a Persian miniature on to the tarmacI buried my reticence, followed her and said, Excuse me. You are the folklorist, Mr Gomal Khotari?

No, but I know Khotari Sahib very well. There was a pause, then, Havent we met somewhere before?

Sometimes it seems as if a larger power gives a damn what you do with your life. One minute you are meandering along the road you have chosen, then suddenly you are shoved up a side street where small enticements, like crumbs laid down for a bird, encourage you to believe that you are meant to travel in this direction though you can see nothing familiar up ahead. I glanced at the surrounding strangeness, at this least forgettable of creatures and said, I shouldnt think so.

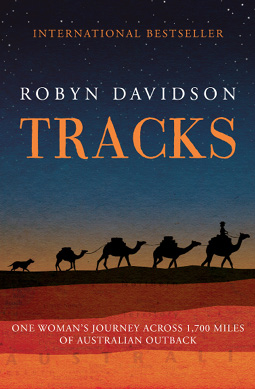

But of course, you are the woman who walked across Australia with some camels. Ive just been reading about you. You must come and stay in my home. My father will be delighted to meet you. How odd that you should arrive here just as I was thinking of writing to you.