Sanjaya Baru - Indias Power Elite: Class, Caste and Cultural Revolution

Here you can read online Sanjaya Baru - Indias Power Elite: Class, Caste and Cultural Revolution full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2021, publisher: Penguin, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Indias Power Elite: Class, Caste and Cultural Revolution

- Author:

- Publisher:Penguin

- Genre:

- Year:2021

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Indias Power Elite: Class, Caste and Cultural Revolution: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Indias Power Elite: Class, Caste and Cultural Revolution" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Indias Power Elite: Class, Caste and Cultural Revolution — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Indias Power Elite: Class, Caste and Cultural Revolution" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN BOOKS

In memory of my father,

B.P.R. Vithal (19262020),

and my father-in-law,

A. Vaidyanathan (19312020)

It was during my graduate years at Hyderabads Nizam College that I discovered C. Wright Millss The Power Elite in my fathers bookshelf. As a student of politics and economics, I was always fascinated by the study of power. While my discipline was economics, I took particular interest in political economy, which has its origins in the study of wealth and power. It was an interest stirred by the fact that for years I was a silent participant in conversations about policy and politics around me. My father was a civil servant and close to a succession of powerful chief ministers. Conversations about caste and class and the struggles for power were commonplace at home. The communist ideologue Mohit Sen, a friend of the family, argued vehemently about the centrality of class to an understanding of power, while our house guest, Professor Hugh Gray of the School of Oriental and African Studies, London, who was studying the role of caste in provincial politics, would insist on its recognition. I, therefore, grew up in a social milieu highly conscious of both class and caste as social dividers.

In 1974, when I moved from Hyderabad to Delhis Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), I entered an intellectual space in which scholars seemed more familiar with class than caste. The study of caste was viewed as a preoccupation of sociologists. The communists accused right-wing scholars of emphasizing the importance of caste, to shift the focus away from class. The left imposes Western theoretical constructs on India, its critics would retort, for caste is a more important institution of power and discrimination than class. These were familiar intellectual battles of the 1960s and 1970s. Caste politics was yet to graduate out of the provinces and overwhelm national politics. One event that brought a huge change to the way political parties and analysts thought about politics was the Emergencya central political event of the 1970s. Prime Minister Indira Gandhi put almost every political group from the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) to the Maoists in jail. The all-in-one left and democratic unity that was a consequence blurred the debate on caste and class.

The Emergency succeeded, however, in once again bringing out sharp intra-elite cleavages. National politics had witnessed this when Jawaharlal Nehru swerved to the left, and many among the elite moved to the right, joining the Swatantra Party. Indira Gandhi had similarly divided the ranks of the elite with her own leftward swing in the late 1960s. The Emergency united both the left and the right.

Then came the 1980s, and New Delhi woke up to the power of caste divisions when Prime Minister V.P. Singh tried to consolidate his political base by extending caste-based reservations in education and employment.

My interest in the dynamics of power was reignited when I returned to New Delhi in the 1990s as a journalist. I observed from close quarters the politics that shaped Prime Minister P.V. Narasimha Raos five-year tenure and the rise of Atal Bihari Vajpayee. When Rao became prime minister (PM), journalist Saeed Naqvi declared him the last Brahmin prime minister of India. two years, Vajpayee, from the heartland of north-Indian Brahminism, took charge and, as of now, owns that title. He may well end up being the last Brahmin PM considering the direction the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) politics has taken under the leadership of Narendra Modi and Amit Shah, with its empowerment of the middle castes, referred to as Other Backward Classes (OBCs).

Unlike most economists, I did not see the economic liberalization of 1991 in purely ideological and economic theoretical terms. It was not just about neoliberal economics taking over Fabian socialism or free enterprise winning over state capitalism. The central element of the 1991 reforms was the end of the Licence-Control-Permit Raj, the original crony capitalism that had thrived in Indira Gandhis centralized political regime. The policy shift was as much about changing power equations within the elite as it was about ideology.

A new post-Green Revolution business class with rural roots, located in states like Punjab, Haryana, western Uttar Pradesh, Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh, had risen and was challenging the dominance of the essentially metropolitan Marwari business elite of Bombay (now Mumbai) and Calcutta the pyramid of power in India. An entire class of the New Delhi-based elite that constituted the Delhi Darbar of the Nehru-Gandhi dynasty was now being forced to adjust itself to the power shift.

When I was reading Millss The Power Elite in the 1970s, in my home in Hyderabads upmarket Banjara Hills, a relative who had lived most of his life in the Andhra districts and was ill at ease in the still-nawabi culture of Hyderabad mocked me by saying that I might have been reading a book critical of the American power elite, but was I not a member of Hyderabads power elite? It is a remark that has stayed with me through the years as I have tried to understand the hierarchy of power and elitism in India.

When I moved to JNU in the 1970s, I came face to face with the countrys national power elite. Many of my contemporaries were from boarding schools set up by maharajas, and upmarket colleges in Delhi, Calcutta and Bombay, run by British missionaries. They were more self-confident in their class than a Hyderabadi like me. That is in the nature of the hierarchy of power and elitism.

In the 1970s I was viewed as an outsider by the power elite of Lutyens Delhi. In the 1990s, as an editor at the Times Group and someone who knew Prime Minister Narasimha Rao well, I was welcomed into the charmed circle of the Lutyens elite. I was invited to seated dinners, Hindustani classical baithaks and fancy cocktail parties in Lutyens Delhi and homes around Khan Market. The Nehru-Gandhis had gone, but their darbaris survived the Rao-Vajpayee-Manmohan Singh era. When I became a member of the India International Centre (IIC), I had perhaps earned my credentials as a member of the national elite. I could leave my provincial past behind and become a card-carrying member of Lutyens Delhi, a term that Narendra Modi gave currency to.

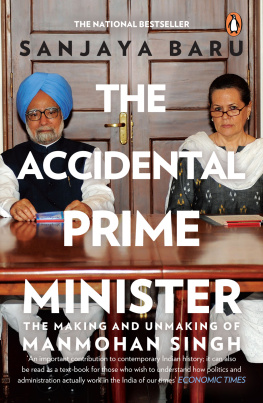

After having acquired membership of Lutyens Delhi, I entered the sanctum sanctorum of the Delhi darbar as an adviser to the prime minister. One of the privileges of becoming an adviser to the PM, I discovered, was a temporary membership of the elite Delhi Gymkhana Club, a feudal vestige of the British Raj. For the period one was a member of the PMs charmed circle, the club had made a provisionone could become a VIP member under the clubs Eminent Persons category. The day I quit my job, my membership ceased, and I was promptly reminded of it. When my book The Accidental Prime Minister: The Making and Unmaking of Manmohan Singh appeared, many readers around the country said it offered them an insight into the corridors of power, while most members of the Nehru-Gandhi darbar criticized me for doing precisely thatopening a window to the outside after having entered its door. The courtiers regarded it as betrayal. It is in the nature of elite clubs that once you are in, you keep other outsiders out.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Indias Power Elite: Class, Caste and Cultural Revolution»

Look at similar books to Indias Power Elite: Class, Caste and Cultural Revolution. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Indias Power Elite: Class, Caste and Cultural Revolution and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.