Table of Contents

CONTENTS

>

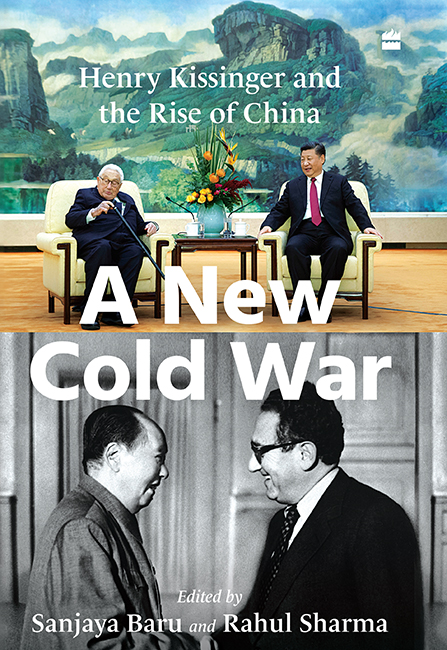

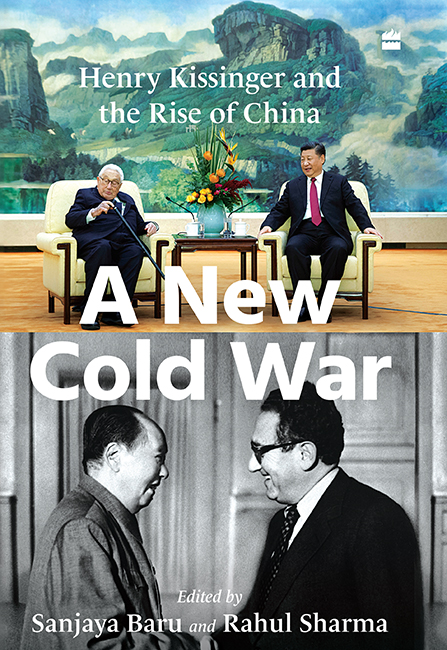

X INTIANDIA NAME THAT TRANSLATES AS New Heaven and Earthis today an upmarket, pedestrian-only district of Shanghai, full of trendy shops, restaurants and bars. A China tourist guide says it is the place that youngsters love the most. A century ago, in July 1921, the Communist Party of China (CPC) came into being in a small building in this neighbourhood. In July 2021 the Peoples Republic of China will mark two historic anniversaries. First, the centenary of CPCs formation and the convening of the First Party Congress. Second, the fiftieth anniversary of a historic reconciliation between the worlds most populous communist country and the worlds most powerful capitalist country. Chinas supreme leader and the Great Helmsman, Mao Zedong, was present in that Xintiandi house when the CPC was formed in 1921. Fifty years later he met with the emissary of the president of the United States of America, Henry Kissinger, to redefine ChinaUS relations and the global balance of power.

Ironically, China marks these two anniversaries at a time when the onset of a New Cold War with the US looms large. Even as geopolitical analysts were writing newspaper columns and addressing online webinars recalling the events of 1921 and 1971, the US Secretary of State Anthony Blinken met his Chinese counterpart, State Councillor Wang Yi, in snow-covered Alaska in an icy interaction in which no punches were pulled. In an exchange marked by mutual recrimination, Blinken and Wang traded barbs and charges that prompted several analysts around the world to say that the Alaska meeting was the defining moment of a New Cold War.

Against this background, it is relevant to recall that the reset in the USChina relationship in July 1971 played a vital part in finally bringing to an end the Old Cold War. That Cold War, between the US and the Soviet Union, came to an abrupt end as several parallel political and economic developments of the late 1980s across Europe resulted in the fall of the Berlin Wall and re-unification of Germany, the upheavals in the Soviet and European communist parties and the failure of perestroika in preventing the fallout of glasnost. The USChina reset of 1971 played its own role altering the geopolitical environment within which the Soviets, the European and Asian communists were acting. A China intent on recovering its own national status as a civilizational power, abandoned the principles of communist internationalism and embraced what has euphemistically been dubbed socialism with Chinese characteristics.

The new development path that China pursued under the leadership of Maos old comrade and detractor, Deng Xiaoping, with the enthusiastic support of the US, enabled it to emerge as the second-most powerful nation today, next only to the US. In seeking to vanquish one challenger, the US sowed the seeds, so to speak, that have since blossomed into a new challenger. Chinas historic rise, enabled partly by US investment and business opportunity, has created the basis for a New Cold War as Beijing rejects the existing balance of global power and seeks a greater say for itself in Asian and world affairs.

The transformation that China underwent in the first fifty years of the past century was historic and of great significance for its own people. It was globally significant, too, as the ruling Communist Party worked towards enhancing Chinas economic heft that also allowed it to build a new social contract with the citizensprosperity in return for political status quo. Beginning with the reset of bilateral relations between China and the US, following Henry Kissingers July 1971 visit and the subsequent visit of President Richard Nixon in February 1972, communist China set itself on the path of modernization. Looking back at the NixonKissinger outreach of July 1971 and the reset in the USChina relations over the past half a century, these essays seek to understand the role played by Kissinger, both as a senior US government functionary and as a lobbyist for China in global corridors of power. The essays are divided into two sections: those that examine the global implications of the USChina reset and those that look at this process from the perspective of select countries.

It was in a 1968 speech that he had drafted for Nelson Rockefeller that, says Teresita Schaffer, Kissinger first drew attention to the need for a relook at the US policy towards China. The event that prompted this was the border conflict between the Soviet Union and China for it indicated clearly that the SinoSoviet alliance that the West had taken for granted until then was now coming apart. While the US policymakers had, after 1968, devoted considerable time to thinking about establishing diplomatic relations with the Peoples Republic, concrete steps in this direction were taken only after Nixon and Kissinger entered office. Schaffer offers a US diplomats perspective and an interesting peek into Kissingers preparation for his China visit. In Schaffers reckoning the USChina equation established in 1972 altered the post-war bipolar balance of power system irrevocably, creating in its place a new tripolar order. Over the years, however, China utilized the space it secured, thanks to US policy towards it, to build itself up and emerge as a stronger power. While Kissinger helped create a tripolar world order out of a bipolar system, a new bipolarity may yet be emerging.

Henry Kissinger belongs to the pantheon of textbook realists in international relations. Paying tribute to his policy oeuvre, the ardent practitioner of realism, Kishore Mahbubani, asserts the biggest damage done by the abandonment of Kissingerian realist-pragmatism is that the US has become severely weakened both domestically and externally. Mahbubani views the 1971 moment as one of the US coming to terms with Asian reality and argues that it is presently in denial with respect to Chinas inevitable rise as a Great Power. Successive US administrations pursued an effective foreign policy as long as Kissingerian realist-pragmatism reigned supreme in Washington, DC. After the end of the Cold War, both hubris and misplaced liberalism took over, contributing to declining US power and influence. Mahbubani believes President Donald Trump not only got China wrong but, by the end of his tenure in office, has left it a stronger power. American liberals, argues Mahbubani, have to come to terms with Chinas inevitable rise and, to remain globally competitive and in a position to deal with a powerful China, the US must look inwards and invest in the capabilities of its own people and in the institutions and infrastructure needed to build those capabilities.

Kanti Bajpai offers an incisive recounting of the events of 1971 and argues that while Nixon and Kissinger kowtowed to Mao and Zhou, the Chinese duo were more comfortable in their skins and took the new equation in their stride. Bajpai, too, points to the more enduring American fascination with China and warns India that it must keep a watch on any US return to a policy of accommodation with China, preferring to manage the more familiar bipolar world. While NixonKissinger opened up to China, it was the administrations of President Ronald Reagan and Bill Clinton that in fact helped build China up. The US contributed to the modernization not just of the Chinese economy but also its military. The US strategy towards China, suggests Bajpai, was carrots for good behaviour and when that did not work then it was more carrots. Bajpai rejects the Indian view that the world order in the twenty-first century would be characterized by multipolarity. Nor would it be a Chinese century. It would yet again be a bipolar system. The question is whether the US and China would pursue a G-2 condominium or a conflict-ridden bipolarity. Bajpai believes the American elite remain fascinated by China, even if their past indulgences have come home to roost and bedevil the US, and that they have less regard for an India that is still not getting its act together.