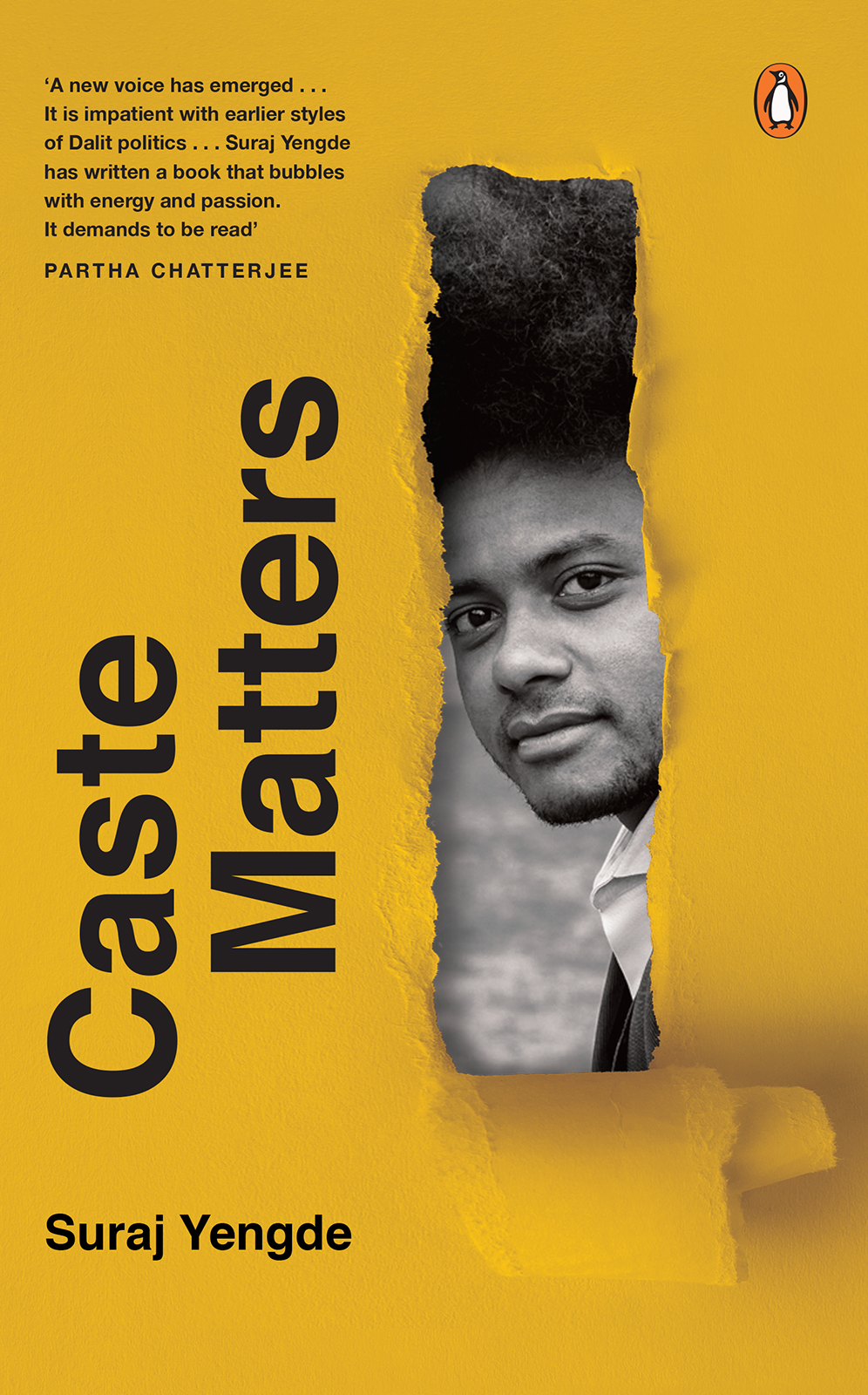

Advance Praise for the Book

A new voice has emerged among the younger generation of Dalits in India. It is impatient with earlier styles of Dalit politics and rejects both ceremonial recognition and opportunist electoral alliances. The new voice is angrier, yet wiser. It promises to learn from the experiences of racially oppressed people elsewhere in the world and offers a more principled strategy of seeking allies. Suraj Yengde has written a book that bubbles with energy and passion. It demands to be readPartha Chatterjee, Columbia University, New York

Suraj Yengdes book is a theoretically sophisticated, anthropologically interesting, historically wide-ranging and morally compelling reflection on caste in India. It is exactly the kind of mirror India needs to look into. It is angry, but takes its anger in a reflective, analytical and productive direction. This book will cement Yengdes reputation as one of the more novel voices confronting the realities of caste in his generationPratap Bhanu Mehta, vice chancellor, Ashoka University

This book about the menacing prowess of caste is an important addition to the anti-caste armoury. It is a must-read for those who display various degree of caste-blindness, saying caste is a thing of the past. It is useful even for those who acknowledge the existence of caste, but believe it would simply melt away under the pressure of urbanization and modernity. For the Dalits, its worst victims, either nothing has changed or things have only become worse. The continuing practice of untouchability, growing number of atrocities and falling markers of development parameters are the hard evidence. But Dalits are not counted within human pathos, their numbers are embedded and hidden.

Caste Matters is an experiential exposition of the hidden side of caste by a promising young scholar who has risen from the dark alleys of his childhood to the academic dazzle of iconic Harvard. It is replete with reflections over the raw experiences of a poor Dalit child as also with the mature commentary about the changes that befell his universeAnand Teltumbde, senior professor and chair, Big Data Analytics, Goa Institute of Management

To aamche papa, Milind Vishwanath Yengde, my man on whose love I continue to build my foundation

And aamchi mummy, Rohini Yengde, for all the love and care she continues to bequeath

The 13 Yengdes:

Chandrabhagabai, Mohan, Sunanda, Deepak, Amrapali, Pavan, Samyak, Nitin, Pranali, Akash, Priyanka, Harsh, Prerana

Introduction

Caste Souls: Motifs of the Twenty-first Century

Taking me into her cushy arms, my aai (paternal grandmother) was reminding me of the importance of my presence in her life. My dearest maajhya baalla, you are so full of life. Youve the best eyes. Youve so many qualities that I can barely count them. Her darkened face and frail skin glow in the night, the cheapest light bulb in the marketknown as zero-power bulb, which truly was a lightless bulbthe only source of light in the room, was switched off. She was consoling me in the room the size of a Toyota Minibus that I shared with her, my mother, father, sister and brother. I shared the floor space underneath the cot with my sick father and brother. Perpendicular to the cot on nylon mats slept my mother and sister.

Running her palm on my face in circles, Aai started massaging my head. Her soft palm had seen everythingthe horrors of untouchability, the traditions of imposed inferiority, and her resolution to labour to build her familys life by working in farms and fields as a landless labourer, a servant at someones house or in the mill. She represents the traditions of unknown yet so great people. The people made outcastes by the Hindu religious order, deemed despicable, polluted, unworthy of life beings whose mere sight in public would bring a cascade of violence upon the entire community.

In India, casteism touches 1.35 billion people. It affects 1 billion people. It affects 800 million people badly. It enslaves the human dignity of 500 million people. It is a measure of destruction, pillage, drudgery, servitude, bondage, unaccounted rape, massacre, arson, incarceration, police brutality and loss of moral virtuosity for 300 million Indian Untouchables.

In school I was humiliated for not paying fees on time. The clerk, Tony, would visit the classroom every quarter and call out my name, asking me to stand up. Once I did, he would read out how many months of fees were pending. The higher the number, the more the embarrassment. My classmates added shame to that embarrassment by quietly staring at me in disgust. This was a regular occurrence. Every time Tony came to class, I wanted to leave school and join the hustlers in my slum; they made money and lived as they wanted, without relying on anyones disrespect to get through the hustle called life.

I grew up in relative poverty in the early part of my life, until I reached sixth grade. After that my family was downgraded to a level below poverty, officially known as Below Poverty Line (BPL). BPL is a state-determined category that calculates the degrees of deprivation. The Tenth Planning Commission fixed seven parameters. Kerala has nine parameters, while Haryana has five parameters to identify families in regard to ownership of land and access to employment, education level, status of children, sanitation, roof, floor, safe drinking water, transportation, food, ownership of colour TV, fridge and so on. In addition, there is an income cap which varies and is adjusted according to ones non-ownership of the above. In Maharashtra, the BPL numbers are premised on the basis of thirteen factors, identifying 46 lakh people (close to 50 per cent of the total population) below the poverty line in the 1990s and 39 per cent in the 2000s. There was, however, no distinction made between families belonging to the Scheduled Caste category and other categories. My family, on the urban fringes, fit into the BPL category perfectly.

Caste is understood through various prisms, thus making it the most misunderstood topic of dialogue on/in India. Caste is thought of as synonymous with reservations, Dalits, Adivasis, manual scavenging, poverty, Dalit capitalism, daily-wage labourers, heinous violence, criminality, imprisonment, Rajputs, Brahmins, Banias, Kayasthas, OBCs, etc. These are some of the many variations that bear witness to the everyday nakedness of caste. However, what remains undiscussed and therefore invisible is the multiple forms in which caste maintains its sanctity and pushes its agenda through every aspect of human life in India. Caste plays an important role in every facet and over an unthinkably large domain of public and private life.

So, my family had no agricultural land, colour TV or fridge and our income level was as low as it could be as my father was bedridden (health reasons meant he remained unemployed for most of our lives). He did not own a house. We lived on an inherited property of 3040 feet, half the size of a basketball courtit was evenly distributed among three families comprising sixteen members in all. Access to sanitation was a struggle as we had only one bathroom and toilet. During the morning hours, cousins and siblings would line up as everyones school started at around the same time. The education level in my house did not go beyond tenth grade. Rusty, corrugated iron sheets that served as the roof were placed on fragile brick walls, pressed down with heavy stones weighing 1020 kg so that they didnt fly in the wind. Iron sheets transmit electrical current, and the chances of the stones slipping was greater during the rainy season. Iron sheets also meant that we got the first intimation of any change in weather. They were our live weather reports. Drizzles would alert us about the arrival of rain. We were the first to notice as those drops made thunderous noise. When it was summer the iron sheets would attract harsh sunlight. Whoever sat underneath them on a good summer day would choke as it was difficult to breathe. Due to lack of insulation the winter did not spare us either. We slept in the house bearing the ruthless weather. Our prayers round the clock were to somehow get rid of those iron sheets. Sadly, they were never answered. Whenever I visited my mothers side of the family I would wake up surprised to notice that it had rained the previous night and I didnt get to knowthey had a thick roof made of cement which made no announcement of rain. The noise of a downpour in my own house made it difficult to sleep. To survive in such a situation, I volunteered to do odd jobs, desperately looking for temporary relief despite my parents resistance. Once I thought of joining the boot factory where my friends from the area worked as manual labourers. Another time I worked on groundnut soil in the fertile region of Vidarbha, accompanying my mothers family; I worked as a manager overseeing my fathers newspaper; I worked as a helper to a truck driver; I worked in a warehouse, all in my attempt to make ends meet. I did all this before I reached puberty.