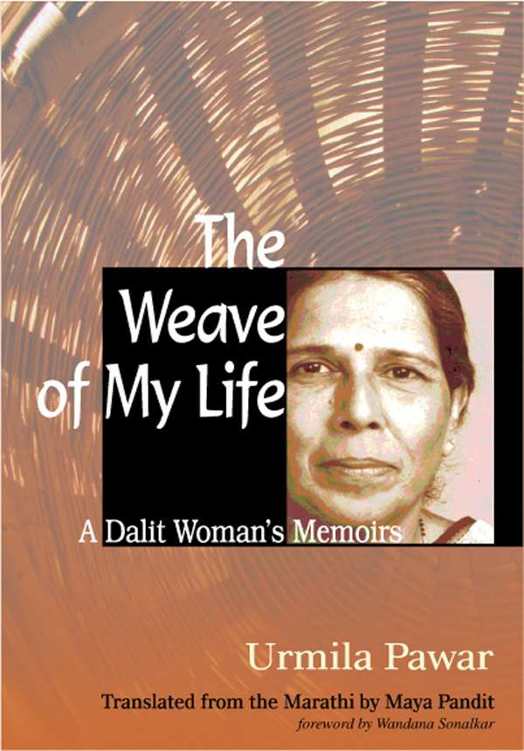

THE WEAVE OF MY LIFE

Urmila Pawar

The Weave of My Life

A DALIT WOMANS MEMOIRS

URMILA PAWAR

TRANSLATED BY MAYA PANDIT

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS NEW YORK

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Aaydan copyright 2003 Urmila Pawar; English translation copyright 2008 Stree.

Copyright 2009 Columbia University Press

The Weave of My Life: A Dalit Womans Memoir was first published by Stree, an imprint of Bhatkal and Sen, 16 Southern Avenue, Kolkata 700 026, India, in 2008.

This edition for sale in North America only

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-52057-7

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Pavara, Urmila.

[Ayadana. English]

The weave of my life: a Dalit womans memoirs / Urmila Pawar; translated by Maya Pundit.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-0-231-14900-6 (cloth: alk. paper)

1. Pavara, Urmila. 2. Authors, Marathi20th centuryBiography. 3. DalitsIndiaMaharashtraBiography. 4. WomenIndiaMaharashtraBiography. 5. Political activistsIndiaBiography. 6. FeministsIndiaBiography. 7. Maharashtra (India)Biography. I. Title.

PK2418.P344Z463813 2009

891.4'687109dc22

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

References to Internet Web Sites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing.

Neither the author nor Columbia University Press is responsible for Web sites that may have expired or changed since the book was prepared.

To the memory of my mother, Laxmibai

Contents

Aaydan! What does it mean?

Before plastic began to be utilized for making different objects of everyday use, bamboo was the most common material used to make baskets, containers, and other things of general utility in households. Aaydan is the generic term that refers to all things made from bamboo; awata is another word. Outside the Konkan, the job of weaving bamboo baskets was traditionally assigned to nomadic tribes like the Burud. In the Konkan region, however, it was the Mahar caste that undertook this task. Nobody knows why. Even today, the practice, though considerably weaker, is still prevalent.

The other meanings of aaydan are utensil and weapon.

My mother used to weave aaydans . I find that her act of weaving and my act of writing are organically linked. The weave is similar. It is the weave of pain, suffering, and agony that links us.

When I look back upon my life, I see the period of conversion from Hinduism to Buddhism as its most significant. Neither the children nor the elders had any idea what religion or conversion meant, of its significance, and about who could act as our guide as far as conversion was concerned. Yet we did convert. The meaning of the transformation began to become clearer to us gradually through the changing rituals and traditions and through the guidance of our political leaders.

Dalit houses in the Konkan region were usually not located on the margins of the village but found at its center, probably as a matter of convenience for the upper castes, who could summon us at any time and wanted us at their beck and call. The community was haunted by a sense of perpetual insecurity, fearing that it could be attacked from all four sides in times of conflict. That is why there was always a tendency in our people to shrink within ourselves like a tortoise and proceed at a snails pace. This slow pace picked up radically after the conversion to Buddhism. To begin with, there was a tremendous interest in the new religion and in the images of the Buddha and Dr. Ambedkar. Initially it was difficult to replace the images of Gods with those of the Buddha and Ambedkar. The age-old habits of praying to the Gods, worshipping them for some boon or praying for help in difficult times, were too strong to be given up. Then we came to know from our leaders that one was not supposed to pray to these images for selfish motives, individual benefits, or getting some personal wish gratified. The new way of looking at religion had already given us what we needed; we learned that we folded our hands to the Buddha not as a dharma but a dhamma a way of life, with tremendous social strength. At that time, of course, all this was new and way beyond our understanding!

The other interesting thing was the white clothes that we were asked to wear. In fact, we had not had sufficient clothes to cover our bodies till then and were therefore thrilled with the white clothes. We also came to know that a new rule had come into existence: one had to wear only white clothes on occasions such as the naming ceremony, marriages, and the last rites. Why white clothes? Our leaders convinced us that white is a color of purity. Just as white clothes display any stain prominently; we had to be careful about our conduct being flawless; so that our characters appeared without any stain. This made the question the non-Dalits asked us, Why give the married woman a widows garb? completely irrelevant and superfluous. Even young children like us learned to answer such questions well. But the principle of ahimsa was a bit difficult to understand. We were used to eating meat. Even the Tathagata had accepted that creatures survived on other creatures lives. But for him the human mind was more important. What he meant was that we should not commit violence for the sake of violence. If you strike someone with a sword, you will receive a similar blow in answer. You cannot conquer people with violence, but with love. Our leaders simplified the Buddhas philosophy for us.

Later on we became acquainted with Dalit literature and participated in the Dalit movement. The word dalit achieved a prominence. Some Dalits themselves opposed this word. Now we have become Buddhists, so why call us Dalits? they asked. Dalit writers defined the word dalit in a new way. Dalit means people who have been oppressed by a repressive social system and challenge the oppression from a scientific, rational, and humanitarian perspective. Now this meaning of the term Dalit is acceptable all over the world. But far more important than mere words such as savarna, avarna, Dalit, Buddhist , or woman is the awareness of each and every individual about who he or she is.

Today, because of education and job opportunities, many Dalits have made a transition from being below the poverty line to the middle class. A Dalit looks no different from any other person in society. This has blunted the edge of casteism or discrimination. Like wild animals fast disappearing from the woods, caste seems to have disappeared. Yet, like a wild animal hiding behind a bush, it remains hidden, poised for attack. People traveling in fast vehicles may not notice the wild eyes looking at them, but those who walk do and are struck with terror.

Women are in a similar position. Today women are aware that they hold up half the sky; are educated and work on an equal footing with men in all walks of life. In that case, I ask myself, where is the Dalit woman in all this? I see two streams of her existence: one, below the poverty line, which is worrisome. This woman lives in slums, beside gutters and dung heaps, on railway stations. With her children in her arms; she ekes out an existence by begging or collecting and selling stuff picked up from the garbage heaps. This woman works herself to death as a maid, doing odd jobs, and tries to send her children to schoolsometimes even to English-medium schools.