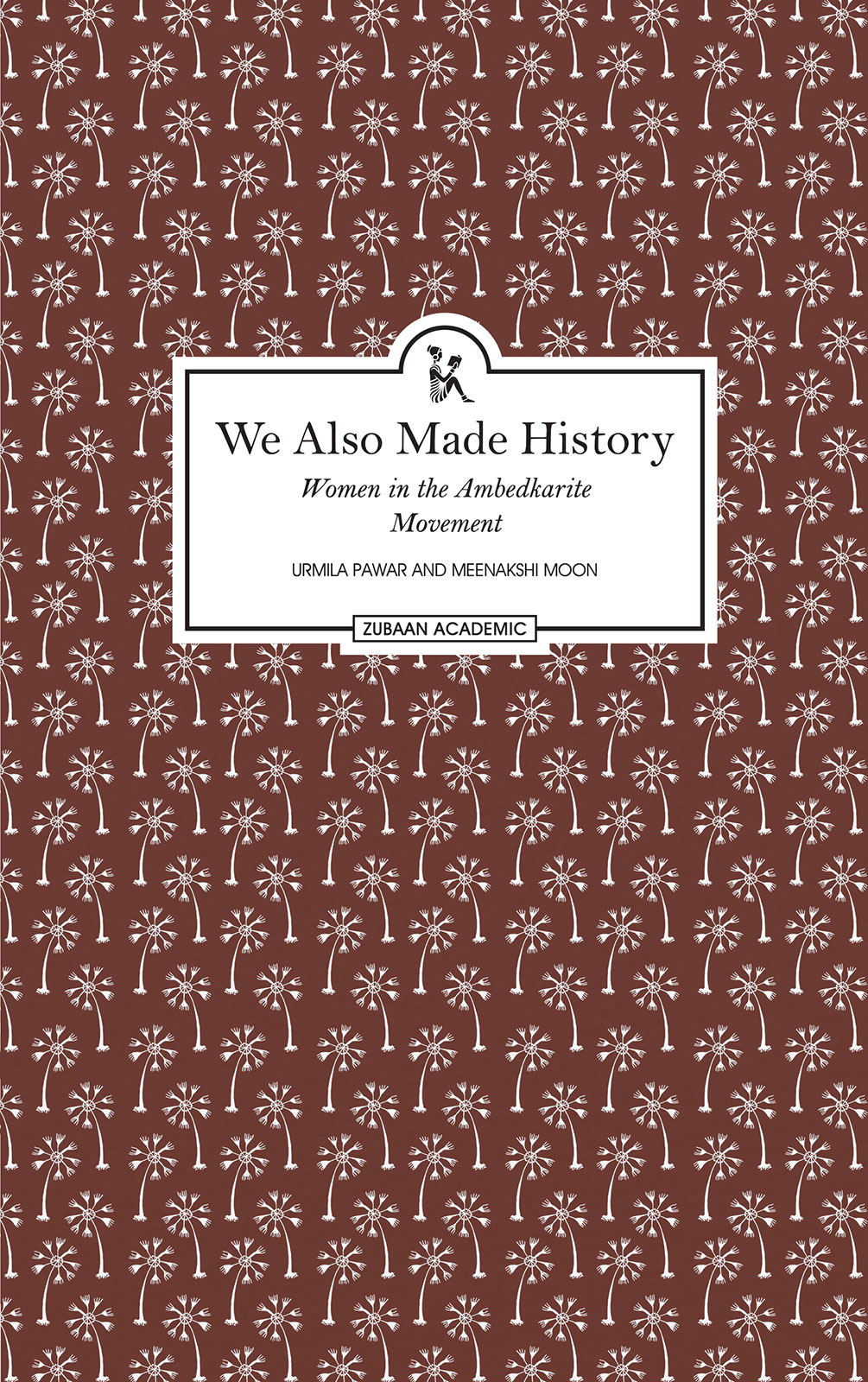

Urmila Pawar and Meenakshi Moon - We Also Made History: Women in the Ambedkarite Movement

Here you can read online Urmila Pawar and Meenakshi Moon - We Also Made History: Women in the Ambedkarite Movement full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2020, publisher: Zubaan, an imprint of Kali for Women, genre: Home and family. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:We Also Made History: Women in the Ambedkarite Movement

- Author:

- Publisher:Zubaan, an imprint of Kali for Women

- Genre:

- Year:2020

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

We Also Made History: Women in the Ambedkarite Movement: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "We Also Made History: Women in the Ambedkarite Movement" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

We Also Made History: Women in the Ambedkarite Movement — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "We Also Made History: Women in the Ambedkarite Movement" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

We Also Made History

Women in the Ambedkarite Movement

We Also Made History

Women in the Ambedkarite Movement

Urmila Pawar and Meenakshi Moon

Translated and with an introduction by Wandana Sonalkar

ZUBAAN

128 B Shahpur Jat, 1st floor

NEW DELHI 110 049

Email:

Website: www.zubaanbooks.com

First published by Zubaan 2008

eBook published by Zubaan Publishers Pvt Ltd 2020

Copyright Original Marathi Urmila Pawar and Meenakshi Moon 2006

Copyright English Translation Wandana Sonalkar, Aalochna 2008

All rights reserved

eBook ISBN: 9789384757366

Print source ISBN: 978 93 83074 74 7

Cover Design: Vandana Bist

Zubaan is an independent feminist publishing house based in New Delhi with a strong academic and general list. It was set up as an imprint of Indias first feminist publishing house, Kali for Women, and carries forward Kalis tradition of publishing world quality books to high editorial and production standards. Zubaan means tongue, voice, language, speech in Hindustani. Zubaan publishes in the areas of the humanities, social sciences, fiction, general non-fiction, as well as books for children and young adults under its Young Zubaan imprint.

Contents

Translators Introduction

T here were different stones down at the river for kunbi women to wash clothes, and different ones for the Mahaars. I purposely washed my clothes on the kunbis stone. Four of them came running in a trice and said, O Mhaarni, have your eyes burst or what? Cant you see its the kunbis stone?

Who are you calling a Mhaarni? So what if I washed my clothes there? Pour water on it and make it pure. What a useless woman this is they retorted. When they said this I ran and clutched the hair of one of them. I hated to be called a Mahaarin, it made me angry. There was a fight. There were four of them but I, alone, was a match for them. Then my father-in-law intervened and ended the fight.

My first verse Ill sing for Bheem

Ill be in the satyagraha and Ill see him

My second verse for him

Who gave us the right to draw water

For him, bai, we re happy in this van.

My third verse is for Ramaais lord,

He made all the people like a happy bride.

The reality of caste practice in village life in todays India is such that the incident narrated in the first paragraph, taken from one of the interviews with dalit women that form the second part of this book, could still occur todaythat is, if a Mahaar woman were to commit such a provocative act. Untouchability has not been banished from India, even though it is banned by law. Separate settlements of dalits are still located on the boundary of a village, on a downward slope, so that water used by them for washing flows outside. Dalits are still denied access to village wells used by other members of the community; their use of common grazing lands and other public spaces is contested by non-dalits. Underlying these exclusions is a threat of violence. And it is the women who bear the additional burden of work, the additional threat of sexual violence, constantly in their daily lives.

Yet the first quote does record a moment of rebellion, a memory cherished by the woman telling the story to the authors of this book. She is Shantabai Sarode, a remarkable woman from the Nagpur region in eastern Maharashtra, who trained as a wrestler and was often called to settle disputes between untouchables and non-dalits. According to her narrative, she went to prison eighteen times. She is indeed a unique personality, even in a gallery of remarkable women; but in the pages of this book we will find several stories of rebellion, rather than the narratives of violence and victimhood that we have come to expect from dalit women. There are of course accounts of early marriages, of abusive and violent husbands, of ill-treatment at the hands of in laws, as we might find in the lives of women of any caste. The social violence underlying the caste system is a reality they have to live with, and it is a subtext that runs through this book. What the book privileges, however, are the moments of overcoming violence, humiliation and exploitation, and the unique form of politicization that made it possible.

The second quote is from a song sung by women taking part in one of the satyagrahas of landless agricultural workers carried out in 1964. Although some dalits in some parts of India own land, and not all the landless are dalits, dalits and adivasis or tribal communities living in or displaced from forest land make up the majority of landless agricultural workers. Some years after the death of B.R. Ambedkar in 1956, Dadasaheb Gaikwad led this movement of dalit agricultural labourers. Dalit women courted arrest and spent time in prison, often with babies in their arms. The Bheem in the verse is of course an affectionate reference to Ambedkar. Ramaai is Ramabai Ambedkar, his first wife, referred to as Rama-ai aai means mother in Marathi.

Dalit popular culture is full of references of this kind. The history of the dalit movement during Ambedkars lifetime is a living part of dalit consciousness today, even as the generation that remembers Ambedkars leadership grows older and gradually dies out. Songs about the struggles, about Bheem, about Ramaai who is venerated as a mother figure, are sung on various occasions when dalits, especially in Maharashtra, gather to celebrate, to commemorate or to protest. And yet, the specific and particular point of view of dalit women themselves rarely becomes a part of this cultural expression.

There are certain historical reasons for this. The Ambedkari jalsas that were built up as a cultural medium of the dalit movement towards the end of Ambedkars life and which flourished in Maharashtra for some time after his death, used elements of existing folk forms such as the tamasha as well as religious forms, but their performances and their troupes did not include women. This was because the appearance of dalit women in tamashas had always been heavily imbued with the culture of their sexual exploitation, of their availability to men of the upper castes. The exclusion of women from the jalsa troupes was thus motivated by the objective of emancipating them from this history of sexual exploitation. Throughout his life Ambedkar endeavoured to bring dalit women into public life in a new role, as speakers and chairpersons in public meetings, as movers and seconders of resolutions, and as teachers. The numerous accounts of women performing this role, which we find in both parts of this book, should be read in this light.

The exclusion of women from the jalsas however, implies that the voice of the dalit woman speaking for herself has been largely absent from dalit popular culture even up to the present time. The few autobiographies by dalit women that have been published in the last two or three decades have been rare exceptions.

That is why this book gives us a unique opportunity to witness two kinds of self-expression by dalit women: firstly, our two authors as narrators of womens participation in the struggles of the untouchables, and secondly, as biographers and interviewers of women activists in that struggle. The first part gives an account of the participation of women in the Ambedkar movement and of previous struggles of dalits from the beginning of the twentieth century. The second part of this book has interviews and brief biographical sketches of some of these women. It should be read, firstly, keeping in mind that Ambedkar, like Jyotiba Phule before him, was very clear about the fact that the subjugation of women is central to the reproduction and sustenance of the caste system, and that thus, the emancipation of women, especially the women at the bottom of the caste hierarchy, is crucial to any struggle against caste and untouchability. And yet, accounts of the Ambedkar movement and its reflection in the culture of the dalits, its mythology, its songs, its icons and its stories of courage and sacrifice, have inadequately taken note of the point of view of dalit women themselves. Thus the text gives us an oblique angle, a cutting edge which can renew our understanding of the dynamics, the motive forces and the contradictions of that movement, and of man-woman relationships among the dalits, which are troubled by the way in which dalit women are used by upper-caste men to maintain the caste hierarchy. The text is also important because it is an account put into words by two dalit women at a particular point in time; it is their reading of this history, a script put out in the evolving scenario of how caste politics, which includes cultural politics, is being played out in contemporary India.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «We Also Made History: Women in the Ambedkarite Movement»

Look at similar books to We Also Made History: Women in the Ambedkarite Movement. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book We Also Made History: Women in the Ambedkarite Movement and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.