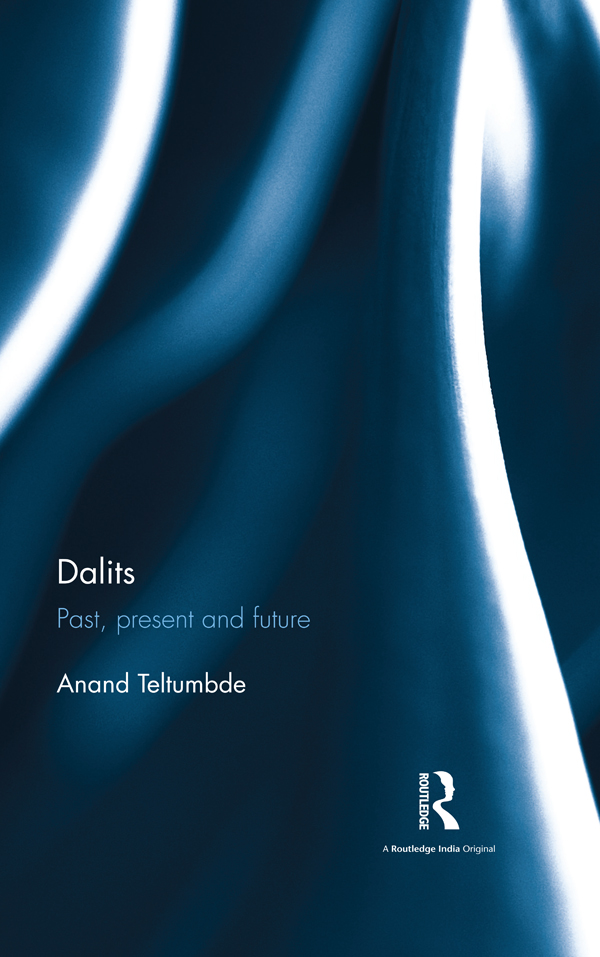

First published 2017

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

and by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

2017 Anand Teltumbde

The right of Anand Teltumbde to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice : Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record has been requested for this book.

ISBN: 978-1-138-68875-9 (hbk)

ISBN: 978-1-315-52645-4 (ebk)

Typeset in Goudy

by Apex CoVantage, LLC

This book may serve as an introduction to a mass of people in India who until a century before lived at a subhuman level as untouchables, unapproachables and even unseeables. They were victims of the caste system, which has the veritable distinction of being the longest-surviving man-made system in the world. Although one finds remnants of caste-like stratifications in some parts of the world, they are not quite the same. The very fact that they died leaving just some reminders of their existence, pales before the caste system in India, which not only survives but also threatens the present. Indeed, it remains unique to India.

There have been a plethora of studies which have tried to describe, at times theorise and still less, think of dealing with castes. But there is not much that has been said of a unified theory of castes. This book is an addition to a long list. While dealing with the Dalits, its core subject, it inevitably deals with castes too. Where it distinguishes itself from many of them is in its comprehensive coverage right from the origin of castes to their contemporary state and in providing at places critical insights to provoke readers into thinking for themselves. I do not know of any book that does it. It should provide a platform for readers to take off from. Readers can then think through the issues and develop their own insights in due course. As such, I hope it will be quite helpful to the researchers besides being a repertoire of information on caste and the Dalits.

Therefore, this is not an inert study. Such an exercise cannot be attempted absolutely dispassionately. Although I have tried to be as academic as possible, cross-referencing the information sources at questionable nodes, the activist in me overwhelms the academic often, blurring the boundaries between the two. In reality, I do not believe that the author can really keep himself aloof from his writing. Even the dead facts of history do not escape the perspective of their presenter. When one writes about live contemporary subjects such as the Dalits, and has some way been a part of them, as an activist, an observer and a commentator, the subjective coating may not be entirely avoidable. I have tried to separate pure information and my views as far as possible in the text in order to facilitate readers to have their own perspective. I leave the rest to readers judgement.

My thanks are due to my young friend Devendra Ingle, who provided me referencing assistance whenever I sought it, to my old colleague Arvind Krishnaswamy, who went through the entire manuscript and suggested important changes, to my nephews Swapnil and Vishal Bhele for their assistance in indexing and to my wife Rama who assisted me in various personal tasks.

I hope the readers will benefit from this labour of love.

Contents

7

Politics as the Master Key

Kanshi Rams plunge into electoral politics unduly surprised many of his comrades. They did not know that Bamcef was just a strategic first step to launch a full-fledged political party. Without resources men, money and organisation the task of creating a winning constituency would be impossible. The example of disintegration of the RPI had provided him ample amount of learning as he would say in terms of how not to do the things. In the strategic sense, Bamcef was meant to mobilise resources and overcome weaknesses in terms of the lack of self-confidence in Dalits. He was the first one to realise that there were significant numbers of resources that could be marshaled for Dalit politics but they lay untapped in the supposedly apolitical mass of Dalit employees of the government/public sector undertakings (PSUs). These people represented the entire investment of the community. With their education, secure jobs, capacity to pay and network they could together constitute a huge resource base. With this vision Kanshi Ram had launched the Bamcef. Once he created a formidable organisation, accumulated financial and people resources, he naturally plunged into active politics to make a bid for power. The DS4 was just a short-lived intermediate step before he would launch a full-fledged political party Bahujan Samaj Party which would stun people with its astute electoral strategies.

Kanshi Ram the strategist

Whatever little is written on Kanshi Ram is heavily affected by the dazzling electoral successes of the BSP. A man coming from nowhere who forsook all ties with his past and present to shape the future with just grit and determination as his sole resource; raised an army out of the most unlikely people, the government employees, to catalyse a political movement that would capture power in the most unlikely state of India, Uttar Pradesh, and sent tremors across the entire political establishment, Kanshi Ram should rightly be considered as one of the few strategic political geniuses that India has produced. A man who stood the ideological Ambedkar on his head and still claimed to pursue his mission, made a virtue of the vice of opportunism that had plagued the post-Ambedkar Dalit leadership and still achieved spectacular success, was indeed a political genius. Whichever way history pronounces its verdict on him, it can never ignore the fact that he was an extraordinary strategist, organiser of people, communicator to the masses and focused implementer of strategies in the history of electoral politics of India. Whether he has contributed to empowerment or emancipation of Dalits, as he and indeed many people believed he was doing, is however a difficult question to answer.

The electoral strategy Kanshi Ram followed would rank as a masterpiece. First, his choice of Uttar Pradesh, instead of either Punjab, his own state, or Maharashtra, the state where he began his social activities, reflected his power of analysis. Uttar Pradesh had a demographic uniqueness of a single caste of Jatav/Chamars comprising 56.3 per cent of the Dalit population and 21 per cent of the total population, making the state rank fourth in terms of Dalit population. While other states had a greater proportion of Dalits, they did not have such a large block of a single Dalit caste. For instance, Punjab, with the largest proportion of Dalits (28.9 per cent), had the most populous Dalit caste of Mazhabhis (including Chuhras and Balmikis) constituting 31.6 per cent, which was only 9 per cent of the total population. The next Dalit caste of Chamars along with Ad-Dharmis constitutes 26.2 per cent of the total Dalit population, the balance 42.2 per cent population being distributed among the 37 Dalit castes. Apart from this demographic feature, the Punjabi Dalits are historically divided into many religions such as Sikhism, Christianity and Islam, and into sects like Ramdasias and Ad-Dharmis among Chamars and Chuhras and Balmikis among Mazhabis, which make them an extremely heterogeneous groups. In terms of development, the two major Dalit castes, unlike other states, present an inverse picture. While the Ad-Dharmi Chamars have the highest literacy rate at 76.4 per cent among the SCs, the Mazhabhis, who are numerically the largest community, have the lowest literacy rate at 42.3 per cent. Because of this feature, Kanshi Ram could not make much impact in Punjab despite being a son of the soil.