ARTHUR GROOM was born in Caulfield, Melbourne, in 1904. His father, Arthur Champion Groom, was the member for Flinders in Australias first federal parliament. The family moved to Queensland in 1911.

Groom worked as a jackeroo at Lake Nash station, near the Northern Territory border, before moving to Brisbane in 1926 to work for the Sunday Mail. His first book, A Merry Christmas, was published in London in 1930.

Groom was an avid walker and outdoor photographer. In May 1930 he founded the National Parks Association of Queensland and later became manager and jack-of-all-trades at Binna Burra guesthouse, on the edge of Lamington Park in south-east Queensland. During World War II Groom lectured Australian and American troops on jungle survival techniques.

He continued to write, but moved away from fiction: subsequent books focused on environmental protection, the conservation of Australias great natural wilderness and tourism.

Groom died in Melbourne in 1953, three years after the publication of I Saw a Strange Land.

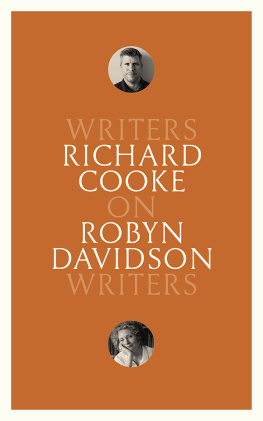

ROBYN DAVIDSON is an award-winning writer who has travelled and published widely. Her books include the bestseller Tracks, about her trek across the deserts of west Australia. Her essays have appeared in such publications as Granta, Monthly, Bulletin and Griffith Review.

ALSO BY ARTHUR GROOM

A Merry Christmas

One Mountain After Another

Wealth in the Wilderness

textclassics.com.au

textpublishing.com.au

The Text Publishing Company

Swann House

22 William Street

Melbourne Victoria 3000

Australia

Copyright Arthur Groom 1950

Introduction copyright Robyn Davison 2015

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright above, no part of this publication shall be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

First published by Angus and Robertson 1950

This edition published by The Text Publishing Company 2015

Cover design by WH Chong

Page design by Text

Typeset by Midland Typesetters

Printed in Australia by Griffin Press, an Accredited ISO AS/NZS 14001:2004

Environmental Management System printer

Primary print ISBN: 9781922182791

Ebook ISBN: 9781925095715

Author: Groom, Arthur, 19041953.

Title: I saw a strange land / introduced by Robyn Davidson.

Series: Text classics.

Subjects: Groom, Arthur, 19041953Travel.

Aboriginal Australians.

Northern TerritoryDescription and travel.

Australia, CentralDescription and travel.

Dewey Number: 919.42904

CONTENTS

Where Jehovah Visits

by Robyn Davidson

Where Jehovah Visits

by Robyn Davidson

BEFORE HORSES and the wheel our species walked: heads up to survey the horizon, down to follow tracks and gather food. The human bodys proprioception, its internal rhythm, is still geared to walking pace. We soothe our babies with it; our deepest understanding of time is measured by it. When we walk, the unconscious (the machinery that takes up most of the brains effort) is free to do its work beneath the surface. Forget Rodins sculptureour best thinking is done on our feet.

There seems always to have been this intuitive connection between walking and cogitating. For the religious, pilgrimage healed the soul. The Greeks philosophised while strolling about. Aborigines went on walkabout as part of ceremonial life.

Where you walk matters as well. City walking is fine if you want to be overwhelmed by stimulus. But country walking, specifically spectacular-landscape walking, allows you to have, as Virginia Woolf put it, space to spread the mind out in.

There is a tremendous freedom in setting off on foot, with minimal fuss and baggage. The constraints of your life fall away, revealing a less cluttered self as pure as a polished shell, said the Buddha.

I know this because I did it myself, back in 1977. And, although unaware of it at the time, I followed in the footsteps of Arthur Groom, a young man who explored the amazing series of parallel ranges that wall the heart of Australia thirty years before I did. I Saw a Strange Land, first published in 1950, is Grooms journal account of this trip. And if it were nothing more than lyric descriptions of the terrain he traversed, it would still be fascinating. Sometimes he uses camels to cart his gear, as I did, but mostly he carries what he needs on his back. He thinks nothing of trudging forty miles a day, or night. (You do not know what forty miles is until you have walked it: through sandhills, up and down plunging broken escarpments, along desiccated riverbeds.)

His evocations of the stupendous landscape uncovered memories that I had thought permanently buried. Muscle memories of scrambling over rocks and spinifex, of freezing dawns and hot days, of the unique intensity of being alone in a terrain that is surely among the most affecting in the world. Because I walked the landscape, slept on it, breathed it, drank it, I feel that, in some peculiar way, that country knows me. I am always homesick for it.

Groom even describes an experience I wrote about in my own journey-book, Tracks. A mournful, unaccountable sound, as of something haunting the air, sometimes far off, sometimes close. Both of us discovered (with relief) that it was the pre-dawn breeze, beginning in the high-up gorges, or in the tops of trees, while everything below remained perfectly still.

The range country of the Centre lends itself to those kinds of feelings. We are awed by its age, power and beauty; astonished at the play of light and colour; inhabited by atavistic reverence. If Jehovah is anywhere, then surely he visits the chasms, escarpments and rivers of those primordial hills.

But ways of seeing are mediated by culture. Aboriginal people who belong there have, I imagine, a different aesthetic response. To them, all land is sacred, therefore it is all beautiful. Yet it was Albert Namatjira who first translated the Centralian colours to a European eye. Arthur Grooms meeting with the Great Man himself, and his talks with Namatjiras teacher, Rex Battarbee, form one of the many beguiling interludes in the book:

Battarbee had been right. Here was natural colour beyond description. It was high up in the sky, with shades of blue and mauve reflected from the cliffs. It was in the patches of green spinifex, clinging in pin-heads on the rubble slopes. It was in the water, the sand, even in the trees; and perhaps the slow-moving deep shadows were more colourful and mysterious than anything else. The colour was in the water-worn rocks of the river bed. There were boulders and slabs of green, grey, mauve, pink, white, red, black, and all the shades between. This colour system was entirely different to the bright colours of the canyon walls. It was of shades and tints, and went up about ten feet to normal flood level, proving that the basic colour of red was gradually being washed out of all the rocks crashing from above.

Groom worries about the effect tourism will eventually have on the area. Will graffiti be carved into the sandstone, or Aboriginal rock art be defaced? But, while it is likely that Jehovah makes himself scarce when buses full of tourists arrive at the better-known gorges and chasms of the MacDonnell Ranges, tourism, it turns out, has been the least of the deserts problems.