Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2014 by Gordon T. Belt

All rights reserved

First published 2014

e-book edition 2014

ISBN 978.1.62584.585.6

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Belt, Gordon T.

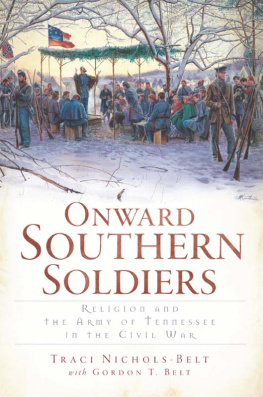

John Sevier : Tennessees first hero / Gordon T. Belt with Traci Nichols-Belt.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

print edition ISBN 978-1-62619-130-3

1. Sevier, John, 1745-1815 2. Governors--Tennessee--Biography. 3. United States--History--Revolution, 1775-1783--Biography. 4. Legislators--United States--Biography. 5. United States. Congress. House--Biography. I. Nichols-Belt, Traci. II. Title.

E302.6.S45B45 2014

976.803092--dc23

[B]

2014006739

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

PREFACE

The revival of memory may be a benevolent compensation to an old man for the loss of hope.

Michael Woods Trimble, 1860

In an anecdote popularized by the nineteenth-century novelist James Gilmore, an old man reminisced about his youthful encounter with Tennessee governor John Sevier. Embellishing the old mans memories with romantic prose, Gilmore wrote of the unbounded affection and admiration that this young boy held for the man known fondly by the frontier people as Nolichucky Jack. As Sevier arrived, the entire town gathered to greet him, and Gilmore recorded the old mans recollection of the scene:

Soon Sevier came in sight, walking his horse, and followed by a cavalcade of gentlemen. Nobody cheered or shouted, but all pressed about him to get a look, a smile, a kindly word, or a nod of recognition from their beloved Governor. And these he had for all, and all of them he called by name; and this, it is said, he could do to every man and woman in the State, when they numbered more than a hundred thousand. The boys father had been a soldier under Sevier, and when the Governor came abreast of him he halted his horse, and took the man and his wife by the hand. Then reaching down, and placing his hand on the boys head, he said: And who have we here? This is a little fellow I have not seen. That he was noticed by so great a man made the boy inexpressibly proud and happy; but could this affable, unassuming gentleman be the demi-god of his young imagination? This was the thought that came to the boy, and he turned to his father saying, Why, father, Chucky Jack is only a man! But that was the wonder of the thinghow, being only a man, he had managed to capture the hearts of a whole people.

Traditional stories like these helped build Seviers standing as a celebrated frontiersman, a revered military leader of the Revolutionary War, a respected and feared Indian fighter and an admired politician and founding father of the state of Tennessee. Pioneer, soldier, statesman: Sevier embodied all the patriotic qualities that his chroniclers hoped to impart to the public. Yet as Gilmores anecdote reminds us, Sevier remained only a man, and although he commanded a strong regional following, Seviers reputation never achieved national acclaim.

In 1860, another aging pioneer named Michael Woods Trimble recalled memories of his father, John Trimble, who served as a captain of a militia company in the regiment under Seviers command at the Battle of Kings Mountain. Michael Woods Trimble took great pride in his fathers associations with Sevier, and in his memoirs, he endeavored to recall the stories of his youth. Trimble wrote:

As I grow old, my memory grows stronger. Especially in this case with regards to the events of my early life. Things which had faded away from my mind many years ago, and had passed into forgetfulness, are revived with all the freshness of recent occurrences. Images of the dead come back to me with faces and voices as familiar as when they lived, and all the scenes through which I passed with them appear to me with more vividness than the events of yesterday. This revival of memory in old age is a mysterious and wonderful provision of Divine Providence. At my period of life, the hopes of this world are nearly all past. But it is said, when one bodily sense is lost, some other becomes strong. The revival of memory may be a benevolent compensation to an old man for the loss of hope.

Over time, as Seviers aged contemporaries passed on, his frontier adventures, military achievements and political accomplishments faded from the publics collective memory. During the late nineteenth century, however, Sevier managed to capture the hearts of his people once more. Years after his death in 1815, Tennessee historians and popular writers attempted to resurrect Seviers legacy through highly romanticized accounts of his frontier adventures, relying heavily on the folktales, myths and recollections of aging pioneers. Through the memories of these elderly frontiersmen, authors and antiquarians retold the tales passed down by the descendants of Sevier and his compatriots, giving these stories a scholarly gravitas that endured for generations. Following the Civil War, the period of Reconstruction brought forth efforts of reconciliation by Southern writers who used stories from Seviers remarkable life to mend the wounds of a broken nation. Subsequent biographers and storytellers repeated these narratives and chronicled Seviers life in ways that reflected Americas culture of patriotism and its embrace of rugged individualism.

In this allegorical depiction of early Tennessee history, John Sevier is the central figure in Dean Cornwells colorful mural Discovery. Tennessee State Library and Archives.

By the early decades of the twentieth century, however, the nations culture had changed. Global war, economic chaos and what one contemporary scholar termed the intrusive thrust of modernism led many writers to bring the past down to non-heroic yet human proportions. Yet the nostalgic remembrances of the past endured.

Still, Sevier remained a regional historical figure, and the stories of his achievements never resonated beyond the borders of his native land. In the preface to the reprint edition of Drivers biography, the authors widow, Leota Driver Maiden, surmised why Sevier failed to achieve national recognition:

Seviers primary interest always remained the advancement of his own State and its people. Consequently, he suffered the same neglect as other public figures who were overshadowed by the acclaim of a national hero, General Andrew Jackson. In the adulation of their first President, too many Tennesseans forgot the man who had protected the early settlements from annihilation by the Indians and later as its Governor guided their State through twelve of its first fourteen years.

Driver christened Sevier Tennessees first hero, and yet he remained second in the hearts and minds of his fellow Tennesseans. Jackson so dominated the annals of Tennessees history that his influence shaped how scholars and writers remembered Sevier for generations. Thus, more than eighty years after Driver first published his biography, Seviers story continues to elude remembrance.