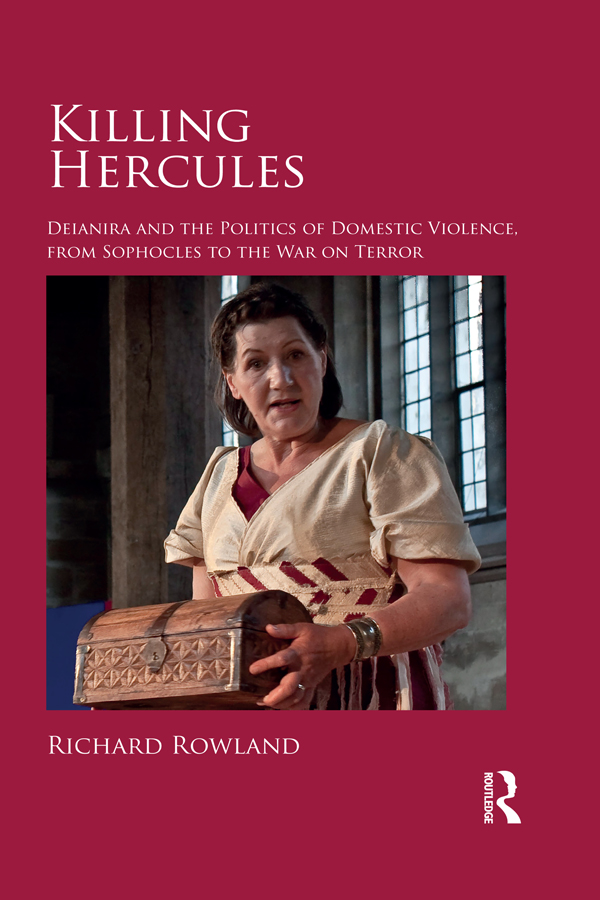

Killing Hercules

This book offers an entirely new reception history of the myth of Hercules and his wife/killer Deianira. The book poses, and attempts to answer, two important and related questions. First, why have artists across two millennia felt compelled to revisit this particular myth to express anxieties about violence at both a global and domestic level? Secondly, from the moment that Sophocles disrupted a myth about the definitive exemplar of masculinity and martial prowess and turned it into a story about domestic abuse through to a 2014 production of Handels Hercules that was set in the context of the war on terror, the reception history of this myth has been one of discontinuity and conflict; how and why does each culture reinvent this narrative to address its own concerns and discontents, and how does each generation speak to, qualify or annihilate the certainties of its predecessors in order to understand, contain or exonerate the aggression with which their governors of state and of the household so often enforce their authority, and the violence to which their nations, and their homes, are perennially vulnerable?

Richard Rowland is Senior Lecturer in Drama in the Department of English and Related Literature at the University of York. He has edited plays by George Chapman and Ben Jonson for the Penguin Dramatists series, Christopher Marlowes Edward II for the Oxford University Press Complete Works, and Edward IV for the Revels series (Manchester University Press). He is also the author of The Theatre of Thomas Heywood, 15991639: Locations, Translations and Conflict (2010).

First published 2017

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

and by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

2017 Richard Rowland

The right of Richard Rowland to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

A catalog entry for this title has been requested

ISBN: 978-1-4724-3402-9 (hbk)

ISBN: 978-1-315-59108-7 (ebk)

Typeset in Times New Roman

by Cenveo Publisher Services

For Bobby, Izzy, Joe, Jessie, Katy, Leanne, Paul and Roger

Contents

Plates

1 Deianira protests to the Chorus

2 Deianira gives the poisoned robe to Lichas

3 Hyllus berates Deianira

4 Hyllus argues with Hercules

Figures

About one third of appeared in Translation and Literature , 22: 1 (2013), and I am grateful to the editors, and to Edinburgh University Press, for permission to reproduce some of that material here. I am also grateful to Faber for permission to quote from Martin Crimps Cruel and Tender .

This book has taken four or five years to write and, perhaps inevitably, some of those to whom I owe most are no longer around to receive the thanks they deserve. Anne Barton brought me back to the world of scholarship after ten years of manual labour, and it was at her instigation that I first started reading ancient Greek drama. The last time I saw her she was very ill, but as I wittered on about this slightly crazy Sophoclean project, she smiled and almost, if unwittingly, quoting the Grateful Dead said what a long, strange journey that will be. I hope she knows that neither this book, nor anything else I have achieved academically, could have happened without her quite extraordinary generosity. One aspect of that generosity was to coerce others into helping me, and the most important of those Anne cajoled was Penry Williams. I took my first faltering steps into early modern history under Penrys wise and endlessly patient tutelage, and my first steps on the hillsides of the Black Mountains under his guidance too. I am profoundly grateful to both and mourn their passing.

I offer thanks to the staffs of several libraries, including the Guildhall in London, the Bodleian in Oxford and the British Library (and especially to the latter, for allowing me to work on Handels actual autograph score of Hercules rather than just the microfilm of it). I would also like to single out for special thanks Nadine Massias, archivist of the Bibliothque Municipale de Bordeaux; Jane Ruddell and Donna Marshall, archivists of the Mercers Company; and Jenny Liddle of the National Trust. Special thanks too to Fazal Sheikh and Sharon Ling for generously allowing me to reproduce their photographs free of charge. The staff of the Library here at York have been unfailingly helpful, particularly when one remembers that we have no Classics department, and, once again, Margaret Dillon has facilitated another of my record-breaking binges on inter-library loans with accuracy and patience. Michael Greenwood at Routledge has been the most helpful of commissioning editors and I am very grateful to him. The students on my Performing Ancient Drama course have been a consistently stimulating bunch and have frequently provoked me into rethinking the ways in which both that module and this book might work.

). Friends and colleagues from elsewhere have also generously provided enormous help in reading sections of the book or answering queries; these include Suzanne Aspden, Pat Easterling, Mike Rodman Jones, Llewellyn Morgan, Natalie Pollard and Carol Rutter. Will Haydon and Craig Farrell have given invaluable assistance with the compilation of bibliographies.

The impact of some scholars on this book has been profound indeed. Isabel Davis read the first draft of the medieval chapter and told me to start again; she was right, and I did. The distinguished Handel scholar Ruth Smith not only read the very long fifth chapter several months sooner than promised, but wrote voluminous commentary on it; her suggested adjustments have been registered on virtually every page of it, and her amusing and encouraging correspondence ever since has been a source of great pleasure. I asked Stephe Harrop to read , and not only made innumerable insightful observations on a project that she has vigorously supported from its earliest beginnings, but castigated my approach to Christine de Pisan because it performed the kind of biographical-rhetorical elision that had the Victorians picturing Chaucer as a rotund little man much given to going out in the morning to see the daisies open. She apologised almost at once, but she was right, and I havent stopped laughing about it since. Fiona Macintosh has a very big presence in this book. Not only has she offered detailed readings of the first two chapters, but it was in conversations with her that the project first took shape, and Im not sure it would ever have been completed without her consistent and enthusiastic support, for which I am eternally grateful. All of these scholars have disagreed with me at times, and all of them have tried valiantly to save me from the most egregious mistakes. I, of course, have stubbornly resisted their best efforts, and the doubtless many errors of judgement and fact that remain are entirely my fault.