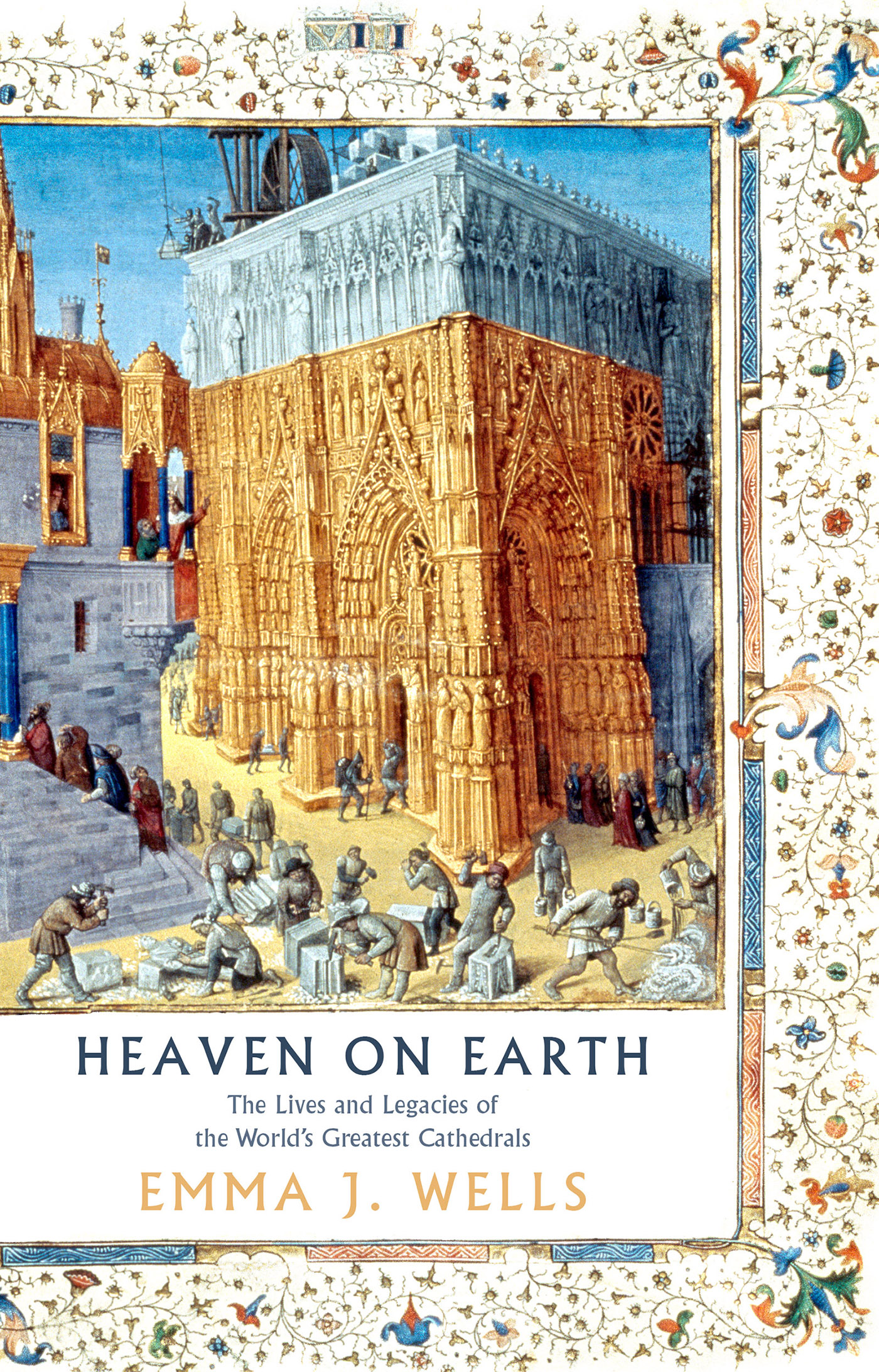

Heaven on Earth

The crossing vault, Salisbury Cathedral.

Heaven on Earth

The Lives and Legacies

of the Worlds Greatest Cathedrals

EMMA J . WELLS

www.headofzeus.com

First published in the UK in 2022 by Head of Zeus Ltd,

part of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Copyright Emma J. Wells, 2022

The moral right of Emma J. Wells to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN (HB): 9781788541947

ISBN (E): 9781788541930

Head of Zeus Ltd

First Floor East

58 Hardwick Street

London EC1R 4RG

www.headofzeus.com

To my parents, friends, colleagues, and Doc without whom this book likely would have been written far more quickly, but who I just wouldnt do without.

Contents

Of nicely-calculated less or more;

So deemed the man who fashioned for the sense

These lofty pillars, spread that branching roof

Self-poised, and scooped into ten thousand cells,

Where light and shade repose, where music dwells

Lingering and wandering on as loth to die;

Like thoughts whose very sweetness yieldeth proof

That they were born for immortality.

William Wordsworth,

from Inside of Kings College Chapel,

in Ecclesiastical Sketches (1822)

high Heaven rejects the lore

And I saw a new heaven and a new earth:

for the first heaven and the first earth were passed away;

and there was no more sea.

And I saw John from the holy city, the new Jerusalem,

coming down from God out of heaven, prepared

as a bride adorned for her husband

And God shall wipe away all tears from their eyes

neither shall there be any more pain: for the former

things are passed away.

Revelation 21:14

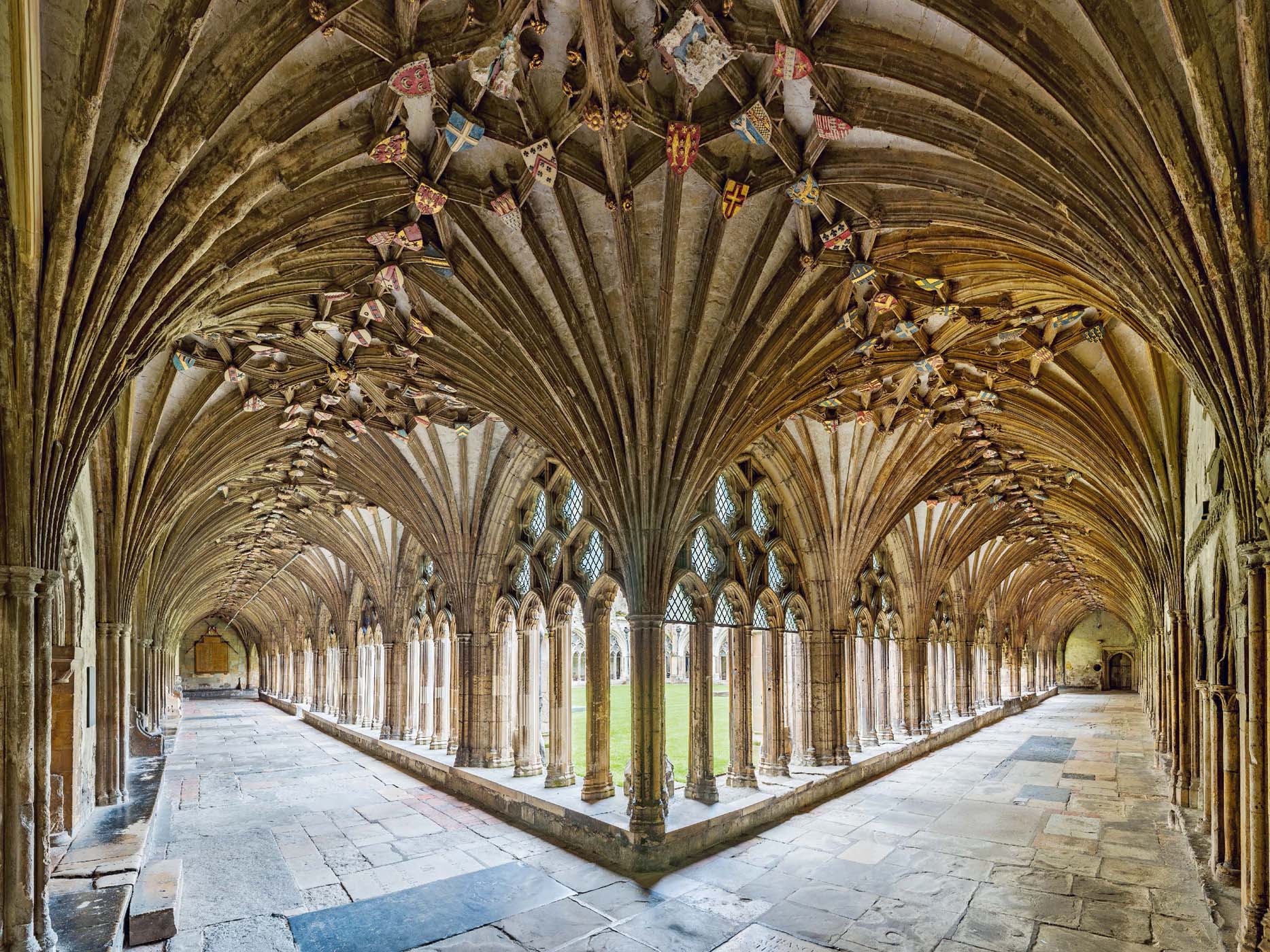

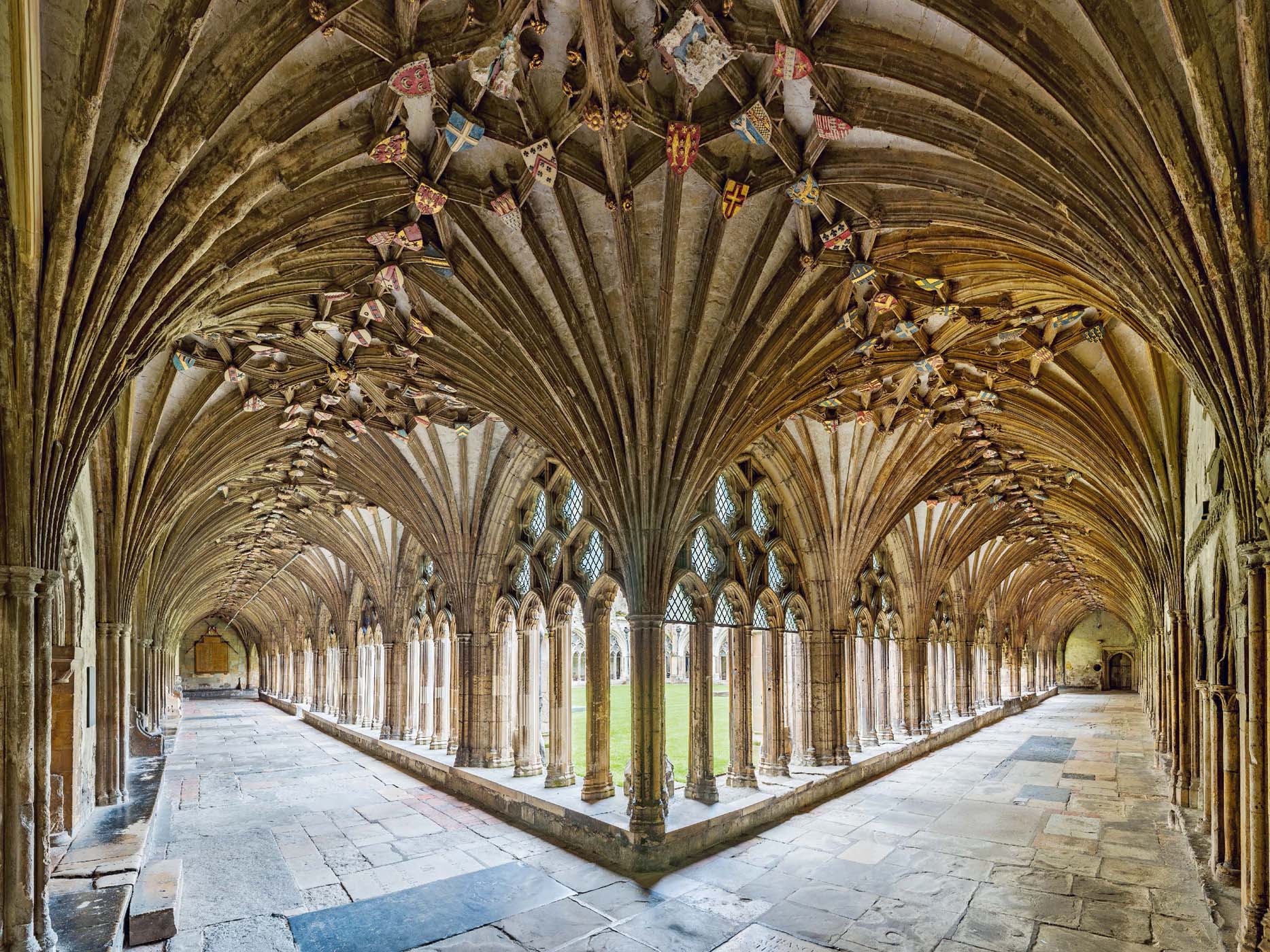

The cloisters at Canterbury Cathedral.

Wikimedia/David Iliff.

So on the threshold of the aforesaid thousandth year the fabrics of churches were rebuilt but every nation of Christendom rivalled with the other ... So it was as though the very world had shaken herself and cast off her old age, and were clothing herself everywhere in a white garment of churches the whole world had been clad in new church buildings [and] the relics of very many saints

RAOUL ( RADULPHUS ) GLABER , Historiae , 10281049

As dusk fell one evening in late October in the year 312, the Roman co-emperor Constantine sat alone in his goatskin battle tent, contemplating orders for the next day. It promised to be one of relentless combat. The Roman Empire into which he had been born was engulfed in a bitter power struggle, characterized by chaos and anarchy. Constantine was in full command of Britain and de facto ruler of Gallia, Hispania and Germania, having inherited this slice of the empire on the death of his father Constantius I, six years earlier. Yet, the four-way division of the empires rule the Tetrarchy created by Emperor Diocletian was falling apart, as its quartet of virtually independent emperors struggled for overall dominance. For Constantine, eighteen years of battling his three competitors was reaching its culmination now, outside Rome.

As he carried his thoughts outside, Constantine looked west, just as a shaft of light from the heavens jolted him from his musings. Two chroniclers Eusebius and Lactantius variously recorded how the light formed into the shape of a cross, the symbol of Christs suffering, gleaming with a fiery glow. In some retellings, the radiant symbol was accompanied by a chant or inscription: In hoc signo vinces! In this sign, conquer! The vision was enough to convince Constantine that his divinely ordained purpose was to restore liberty to his fatherland. Without a moments hesitation, so Lactantius recounts, Constantine commanded his soldiers to mark their shields with a white sign of God: the Christian monogram of the Chi-Ro. Suitably emboldened, Constantine was ready to meet his fate.

The next day, at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge, Constantine was victorious over his rival Maxentius, who drowned in its aftermath. The ramifications were enormous, and not only for Constantine. After three centuries of (at best) indifference and (at worst) persecution, Christianity could finally come out of the shadows. More than that, in celebratory fashion and recognition for his Christian victory, Constantine ordered basilicas churches to be built all over Rome, directly above the cellae memoriae that marked the citys sanctified sites: the tombs of St Peter, St Paul and countless other Christian martyrs.

Most importantly of all, Constantine lavished a portion of the dowry received from his marriage to Fausta, the sister of Maxentius, on the construction of a cathedral. It was built on the Caelian Hill, over the remains of Maxentiuss cavalry barracks and on land belonging to the old Imperial Palace of the Lateran; and it was dedicated to Jesus, the Most Holy Saviour, in gratitude for Constantines victory. So began the worlds first Christian cathedral, the Basilica Constantiniana, later known as the Papal Archbasilica of St John in Lateran.

This imposition of a Christian structure on a Roman military one symbolized Christs superiority over the Roman Empire. It set the stage for Christianity to become its official religion in 380 (via the Edict of Thessalonica), and then for the formation of Catholic Christendom, before worldwide expansion of the Christian religion and its eventual dominance of the Western Hemisphere. And with the creation of that first cathedral, the Bishop of Rome the pope acquired his official seat. Even today, although the pope lives in the Vatican, St John Lateran is considered to be his cathedral and the pope remains Bishop of Rome.

Nearly two millennia later, Europes cathedrals those towering displays of architectural virtuosity are scattered across towns and cities, inspiring admiration and reverence, comprising artful ingenuity and extraordinary engineering, and exuding mystery and sacred significance. For some, they provide consolation during contentious times, hope amid despair; for others, they stand for heritage in the face of destruction, the solidity of the past versus the fragility of the present or uncertainty of the future, and the collective human powers of spiritual and aesthetic expression. Buildings do not talk but we can agree that they are far from mute domains. They have stories to tell.

To begin to grasp what these buildings mean today, we must return to their genesis. When we talk of cathedrals, we normally think of those buildings whose origins are bound up with the history of medieval Europe. It was the Middle Ages, particularly from the eleventh century, that witnessed the mobilization of the spiritual, financial and civic determination to give birth to the buildings we see today, and which inevitably reflected the turbulence of their era. As the most powerful institution of the age, the Church influenced virtually every aspect of life, from first breath to last rite, and faith was forged on an unprecedented scale, out of the furnaces of conflict, craft and creativity. This book takes sixteen examples of great churches all formally cathedrals at some point during their lives, though their histories embraced other names to reflect the grand enterprise of church-building that characterized those times.