On an August evening in 1124, King Louis VI of France received word that his country was about to be invaded by the allied forces of the German emperor and English king.

Louis was surprised - and unprepared - for war. He hurried from his castle in Paris to the Abbey of Saint-Denis - an ancient monastery named for the third-century bishop Louis, believed to be, after God, the singular protector of the realm. In the subterranean crypt of the abbey, he knelt before the bones of the saint and prayed for the safe deliverance of France, pledging a generous donation to the monastery if he should return from battle victorious. Afterward, he visited with his childhood friend and advisor, Abbot Suger, to discuss strategy before mobilizing his troops.

Louis had first met Suger when he was sent to study at the Abbey of Saint-Denis as a boy. Though Suger had come from much humbler means, the monastery school blurred social divisions. The dauphin and the young monk in training developed a friendship that continued as Louis assumed the throne and Suger rose to the rank of abbot.

Abbot Suger understood that the German and English forces would soon advance across its borders. Still, he advised his friend not to respond with force just yet. Thats because the two-pronged invasion had caught the kings army off guard - and left it too scattered to launch an effective counterattack. The monk instead counseled the king to call an assembly of the most powerful clerics and landowners in France and ask them to supply money, material, and men to raise a national army.

King Louis had reason to be skeptical of his friends proposal. To be sure, his reign would mark the beginning of the rise in power and influence of the French monarchy. But at that point, Louiss France, like many kingdoms in twelfth-century Europe, was little more than a loose knot of political convenience. At a time when the line between Church and state was blurred, if drawn at all, the bishops, monks, and feudal lords of the realm vied relentlessly with the king - and each other - for power. Louis knew that at least half the men Suger recommended he turn to for help would be delighted to see him crushed by the invading armies.

The scholarly abbot, however, was not only a man of faith but a shrewd politician. In the people of France, he had sensed a groundswell of devotion he thought could, if properly stirred, work to Louiss advantage.

In the Middle Ages, all wars were said to be holy wars - and all causes considered divinely inspired. Thus, Suger proposed to interpret the political German-English invasion as an attack on the banner of Saint Denis himself. It was Suger himself who had written that Saint-Denis, after God, was the singular protector of the French realm. By enlisting the saint into the cause, he reasoned, few of those invited to attend the meeting could refuse - whatever their feelings about Louis.

Moreover, by turning the invasion into a holy war, Suger made it a matter of concern to Pope Calixtus II. As the bishops and lords of France knew, Calixtus - the former Guy of Burgundy and a Frenchman - would not tolerate an assault on Saint-Denis. They also knew that the pontiff was Louiss cousin and Abbot Sugers friend. One might ignore an invitation from the king or the monk, but to risk offending the pope would be foolhardy.

Abbot Sugers hunch was right.

The influential men of France embraced the holy cause. And soon, King Louis led a large, united army to meet the invaders, who had been counting on French disunity to work in their favor. When the German and English saw the formidable forces assembled against them, they retreated and returned home.

Though Louis had not exactly defeated the enemy in battle, he still considered himself the victor. The influential Abbot Suger became, after the king, the most powerful man in France. (Suger retained his position even after Louis VIs death in 1137. When the new monarch, Louis VII, went to the Holy Land on the Second Crusade in 1147, Suger was named regent of France, and for more than two years, served as chief of state.)

As he had pledged, Louis VI donated a fortune to the Abbey of Saint-Denis, proclaimed it the religious capital of the kingdom and guaranteed it a handsome annual subsidy.

Although the Abbey of Saint-Denis was the most important religious shrine in the country, it hardly looked the part. In many ways, it suffered from its importance and popularity. Besides the remains of Saint-Denis, the church housed other relics: a nail from the cross on which Jesus died and a thorn from the Crown of Thorns. In that age, religion was a palpable presence, and relics attracted the devout. The sheer volume of pilgrims who visited the shrine threatened to destroy it. Abbot Suger had struggled to keep the monastery in good repair. Though they provided a lucrative income for the abbey, the frequent festivals and steady stream of pilgrims took their toll on the structure. On several occasions, bystanders were trampled to death by mobs stampeding to pray before the relics of Saint Denis. Walls, pillars, and floors were cracking.

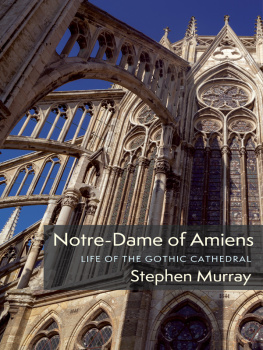

The 300-year-old abbey church was simply not large enough to accommodate the ever-increasing crowds. As far as Abbot Suger was concerned, it was not grand enough either. By the third decade of the twelfth century, he had come to believe that the people of France merited something better. He resolved to build a new sanctuary unlike any other in Christendom - a magnificent shrine to the glory of God.

Later, when he wrote about his great building project, Suger would report that hed been guided by a celestial vision. But there was a large measure of practical concern in the abbots plan. As historian Otto von Simson noted, Saint-Denis... was to be the capital of the realm, the place where the different and antagonistic factions within France were to be reconciled and where they could rally around the patron saint and the king. Both Suger and the king desired an architectural manifestation of the alliance between sacred and secular power.

The man who would be credited with sparking the Gothic movement with this building was a unique exemplar of the combination of sacred and secular power.

Suger, the son of poor peasants, had entered the abbey for an education at the age of ten. Impressed with the boys good nature and intelligence, the current abbot, named Adam, made Suger the companion of the dauphin, the future Louis VI, who also had been sent to the abbey for schooling.

In 1106, Suger took his vows as a monk and became Abbot Adams most trusted assistant. From the start of his tenure as an administrator at Saint-Denis, Sugers practical, worldly education took precedence over his religious vocation. One of his responsibilities: to investigate and alleviate the financial troubles of districts under the abbeys control. At the time, much of the land in Europe was owned by the Church, a state of affairs known as mortmain. As legal owner of all properties within its jurisdiction, the abbey was entitled to a percentage of anything made or grown in the area. Abbot Adam was fair with the inhabitants of his province. But many in the clergy were not: Peasants were allowed to keep only a small portion of their labors.

In his investigations, Brother Suger discovered that when a formerly prosperous district suddenly reduced its contributions to Saint-Denis, it was often because local Church officials were demanding too much from the people in its parish. To address this, the young monk ordered that the obligations under mortmain be reduced. He also included the peasants in the affairs of the Church; drawing people and religion closer together became a lifelong mission. In addition to his diplomatic and administrative skills, Suger proved he had a military flair when he led a peasant army against the troops of a land baron who had been looting farms.