Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2015 by Jon C. Stott

All rights reserved

First published 2015

e-book edition 2015

ISBN 978.1.62585.205.2

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015935102

print edition ISBN 978.1.62619.676.6

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book. Every attempt has been made to give accurate credit to the rights holders of the images contained herein. Any errors or omissions will be corrected in future editions.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Although this book has my name as the author, it could not have been written or published without the help of many people. First, I wish to thank Greg Dumais of The History Press for accepting my proposal and for his encouragement and support during the planning and writing of the book. I also wish to thank Julia Turner of The History Press for her fine editing.

Many people in Michigans Upper Peninsula were also of inestimable help. First and foremost, accolades go to Deb LeBlanc of the U.S. Forest Service. A friend of many years, she has taught me a great deal about the flora and fauna of the area. Because of her, I discovered the Kingston Plains and the Murphy Pines. The visiting of both places gave me a much fuller understanding of what the landscape was like before, during and after the great pine logging era. The photograph of the Kingston Plains is hers.

The officers of many Upper Peninsula historical societies answered my countless questions and spent many hours digging up historical photographs and then making them available for me to use in this book. Thanks go to Darlene Baetke, the Marinette Logging Museum; Amber Allard, Spies Public Library (Menominee, Michigan); Jim Borski (Menominee, Michigan); Rebecca Beck, Menominee County Historical Society; Karen Lindquist, Delta County Historical Society; Pat Munger and Kathy Eager, Grand Marais Historical Society; Jim Carter (Marquette, Michigan); Sue Hutton, Keith Hutton and Mary Jo Cook, Alger County Historical Society; Vonciel LeDuc, Schoolcraft County Historical Society; Vicki James and Bruce Johansen, Ontonagon Historical Society; Rosemary Michelin and Beth Gruber, Marquette Regional History Center; Mark Eby, Castle Rock Gift Store (St. Ignace); and Kevin and Nora Brewster, Haywire Restaurant (Manistique, Michigan).

Special thanks go to Remi and Jennifer Takahashi (Albuquerque, New Mexico), who gave the manuscript a very careful reading. They discovered many of my careless errors and made many helpful suggestions.

And as always, thank you to my daughter, Clare, who offers great support and encouragement to my writing projects.

To all these people, you have helped make this a better book. Its defects remain my own.

INTRODUCTION

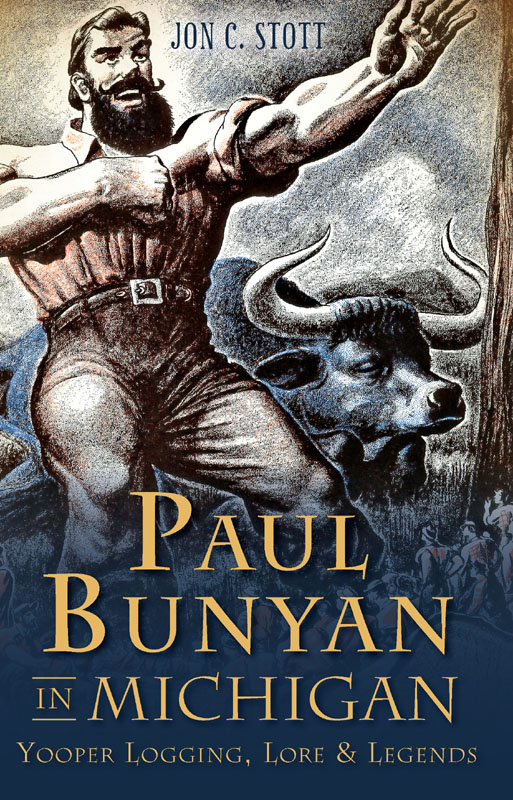

During the later nineteenth century, in logging camps in northern Michigan, Wisconsin and Minnesota, the shanty men would often spend evenings telling anecdotes about unusual weather conditions, incredible logging feats and strange creatures inhabiting the forests. Their narratives drew on logging stories they had heard in other camps and, in many cases, on folklore that they brought with them from their native lands. At some point during this period, the stories coalesced around a fictional logger called Paul Bunyan. He was a kind of super-logger, very large and strong, skilled at all aspects of the trade and a superb leader of men. The events narrated about him were humorous, exaggerated and frequently preposterous and indirectly embodied the mens attitudes toward their dangerous occupation and the frequently inhospitable environments in which they pursued it.

The Paul Bunyan stories did not appear in print until the first decade of the twentieth century, by which time the great white pine logging era had virtually ended and logging operations had moved westward. At first, the stories appeared in newspapers, magazines and professional journals, intended for either local audiences or people in the industry. Then, in 1925, two major publishers put out book-length collections of the tales, beginning a more than three-decade boom of collections of tales, childrens books and even a Walt Disney cartoon about the mythical hero. Although the publications frequently included the same stories, the treatment of these were influenced by the backgrounds of the retellers, their attitudes toward both the stories and the times in which they originated and the times in which their retellings were published.

I first became aware of Paul Bunyan in the late 1960s when I was teaching courses in American studies at Western Michigan University and when my young family and I began to spend summer vacations in Michigans Upper Peninsula. Over the years, I collected versions of the stories and studied the way different storytellers treated well-known episodes. As an English professor working at a time when what became known as the ecological movement was just starting, I was interested in how the stories looked at a type of logging that clear-cut the land, destroying ecosystems and leaving the ground littered with slash that fed the forest fires that completed the devastation the logging companies had begun. I was also interested in how many of the retellers used first-person narrators, a reflection of the fact that storytelling was a major part of loggers leisure time.

When I set about to retell the Paul Bunyan stories myself, I wanted to create a Paul Bunyan who was more realistic, more believable as a human being than the enormous character who walked through trees that were only waist high and who could single-handedly level a forest in a few hours. The Paul Bunyan in my version is a big man, perhaps seven and a half feet tall; he is strong, skilled, intelligent and gifted at storytelling. He enjoys spinning yarns with loggers about the highly improbable events that are frequently told about him.

I also wanted to create a sense of the storytelling culture that existed in the logging camps. So the well-known incidents are set within a framework in which someone tells a story in response to some observation or event that has just occurred. Sometimes, the stories are told by shanty men who seek to frighten a gullible greenhorn. Other times, they are told by Paul himself, either to the men in the shanties or to an individual he is mentoring.

In three of the stories, there are references to actual events and historical personages. I wanted to connect the Paul Bunyan stories to the real world of nineteenth-century logging in the North Country. That is why Paul talks about his mentor Isaac (Ike) Stephenson, one of the most important people in the logging operations along the Wisconsin-Michigan border, and why he visits Peshtigo and Ontonagon after these two towns were destroyed by forest fires. Stephenson is portrayed as a mentor to the young Bunyan, who in later years becomes a mentor himself. While forest fires were a regular occurrence in logging regions and often started as a result of careless logging practices, they are seldom, if ever, mentioned in the retellings. Now that we live in a more ecologically conscious age, it seemed important to consider the causes and consequences of forest fires.