AFTERWORD

Thats Ale, Folks!

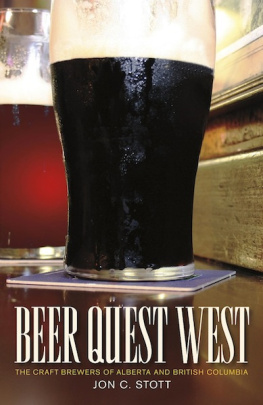

When I told an inquiring neighbour that the book I was about to send the publishers would be called Beer Quest West, he asked about the object of my quest. Was I searching for the ideal pub or the perfect pint, he wondered. And did I find either of them? I explained that my quest was for neither. I wasnt looking for either a Shangri-La for beer drinkers or a Holy Grail filled with a perfect blend of water, malt, hops, and yeasts. The quest was to learn about and experience different kinds of lagers and ales.

After nearly two years of reading, interviewing, and tasting, I found out that there was both a fluidity and a consistency to the beer industry. There were frequent shifts in ownership. In November 2008, Labatt, which had been foreign-owned since the 1990s, became a part of a larger international conglomerate that included Anheuser-Busch of the United States. Labatt joined Molson and Sleeman as large Canadian breweries that had been swallowed by even larger multinational companies. During the two years, eleven new microbreweries and pubs opened and three others expanded or announced expansion plans. Two brewpubs closed and Molson Coors, part of the Miller-Coors-Molson-South African-Brewery conglomerate, purchased Granville Island.

In the brewhouses themselves, there was also fluidity. Traditional English ales and German lagers continued to be made, but young and talented brewers experimented with variations on old styles and created new ones. Ginger, heather, hibiscus, and spruce joined honey, raspberry, and cherry as additives, giving new flavour notes to familiar styles. Several microbrewers began experimenting with lagers, which they admitted were more difficult and unforgiving to create than ales. Beers using wheat malt along with barley malt became popular with craft-beer drinkers. Several brewers introduced little-known Belgian styles that were received with great enthusiasm.

Since the mid-1980s, Molson and Labatt had also introduced new beerslight, dry, ice, and low-carb to name four. But many experienced and cynical drinkers remarked that these were just new wrinkles on the pale North American lagers that had dominated the market for decades. Consistency was an essential element of the megabrewers making and marketing of beers: Bud or Molson Canadian or Coors Light was expected to taste the same no matter where or when it was consumed. As it is for the huge hamburger chains, only controlled surprises were permitted. By contrast, many microbrewers, especially those working for brewpubs, spoke of listening and responding to customer feedback, tweaking their beers to create more interesting flavours, and sometimes pushing style envelopes as far as they could.

I discovered that there were other important constants, not just the essential sameness of each megabrewers North American lager. The first was that opening and successfully operating a microbrewery or brewpub was hard work. There needed to be a lot of start-up capital and, because of the relatively small size of the operations, costs per unit of beer were far higher than for the megabrewers.

Selling their product was also a challenge. Without the enormous advertising budgets of brewers like Molson Coors and Labatt, and the high-profile sponsorship of major league sports telecasts those budgets allowed, microbrewers had to find creative ways of reaching the beer-drinking publicoften, as one brewer said, glass by glass, one drinker at a time. In addition to giving tastings at bars, liquor stores, and beer festivals, these small breweries become involved in the communities where they were located, helping local artists and musicians and amateur sports teams. They also used creativity, coming up with attention-getting nicknames like Pompous Pompadour, Idiot Rock, and Amnesiac.

Another constant was the pride and passion the microbrewers brought to their work. They came from many backgrounds. Most had been homebrewers and some had trained at internationally recognized brewing schools, but many learned on the job, leaving other occupations to earn a living doing what they loved. During my travels, I met a former apprentice stonemason and a former architecture intern, a classical history student and an English major, some civil servants, a motorcycle mechanic, and an oil rig worker. Several admitted that they could have made more money if theyd followed their earlier career paths, but that they wouldnt trade their present professions for any other. They liked creatively brewing a variety of beers and working to make them as good as they possibly could. They liked drinking their own beers and sharing them with others.

Over nearly two years, I had the opportunity to sample several versions of well over sixty beer styles. They had interesting tastes and a great deal of flavour. Each brewers treatment of a specific style was unique. Most of beers were very good, some were excellent. Only a few of them were like pale North American lager, the beer Id consumed for the first quarter of a century of my legal beer-drinking years. Thank goodness!

Because of what I learned and experienced during my Beer Quest West, I now realize that it has no specific end. As long as the brewers of Alberta and British Columbia continue to create so many different and wonderful lagers and ales, mine will be a Never-Ending Beer Quest West.

APPENDIX I

Glossary of Brewing Terms

This short listjust over a bakers dozen of six-packsis designed to give brief definitions of some essential terms relating to beer and brewing. For readers wishing to develop a truly extensive and impressive vocabulary on the subject, Dan Rabin and Carl Forgets A Dictionary of Beer and Brewing (2nd edition) is essential. It contains over 2,500 terms. Descriptions of specific beer styles can be found in Appendix III.

ABV: abbreviation for alcohol by volume.

ABW: abbreviation for alcohol by weight.

additive: an ingredient added to the wort during or after the boiling process to add flavours. Popular additives include fruits or fruit extracts and spices.

adjunct: corn, rice, or another unmalted cereal grain that is a source of fermentable sugar and can be substituted for malted grain (usually barley) in the brewing process. Beers brewed with adjuncts are paler in colour and lighter in body. Beer purists complain that megabrewers use adjuncts to cut costs and that the finished products lack taste.

aftertaste: taste and feel on the tongue after swallowing a mouthful of beer.

ale: one of the two main categories of beer (the other is lager). Ales are created with top-fermenting yeast (yeast that rises to the top of the wort during the fermentation process). They are fermented at temperatures of between sixteen and twenty degrees Celsius and are usually darker, fuller bodied, and more robust in flavour than lagers.

alcohol by volume: in Canada and England, the percentage of alcohol in beer is measured by volume; in the United States the measurement is usually by weight, which, because alcohol weighs less than water, is a lower percentage. Standard mainstream lagers are usually around 5 per cent ABV or 4 per cent alcohol by weight (ABW). Microbrewers often create beers that have higher alcohol by volume percentages, although these do not often exceed 10 per cent ABV. Occasionally, brewers have created strong (sometimes called extreme or big) beers that have even higher ABV percentages.

alcohol by weight: because alcohol weighs less than water, alcohol by weight percentages are lower than alcohol by volume percentages by approximately 20 per cent.

all-grain beer: beer brewed using only malted grains. No malt extracts (syrup made from malt) or adjuncts (such as corn or rice) are used.