Contents

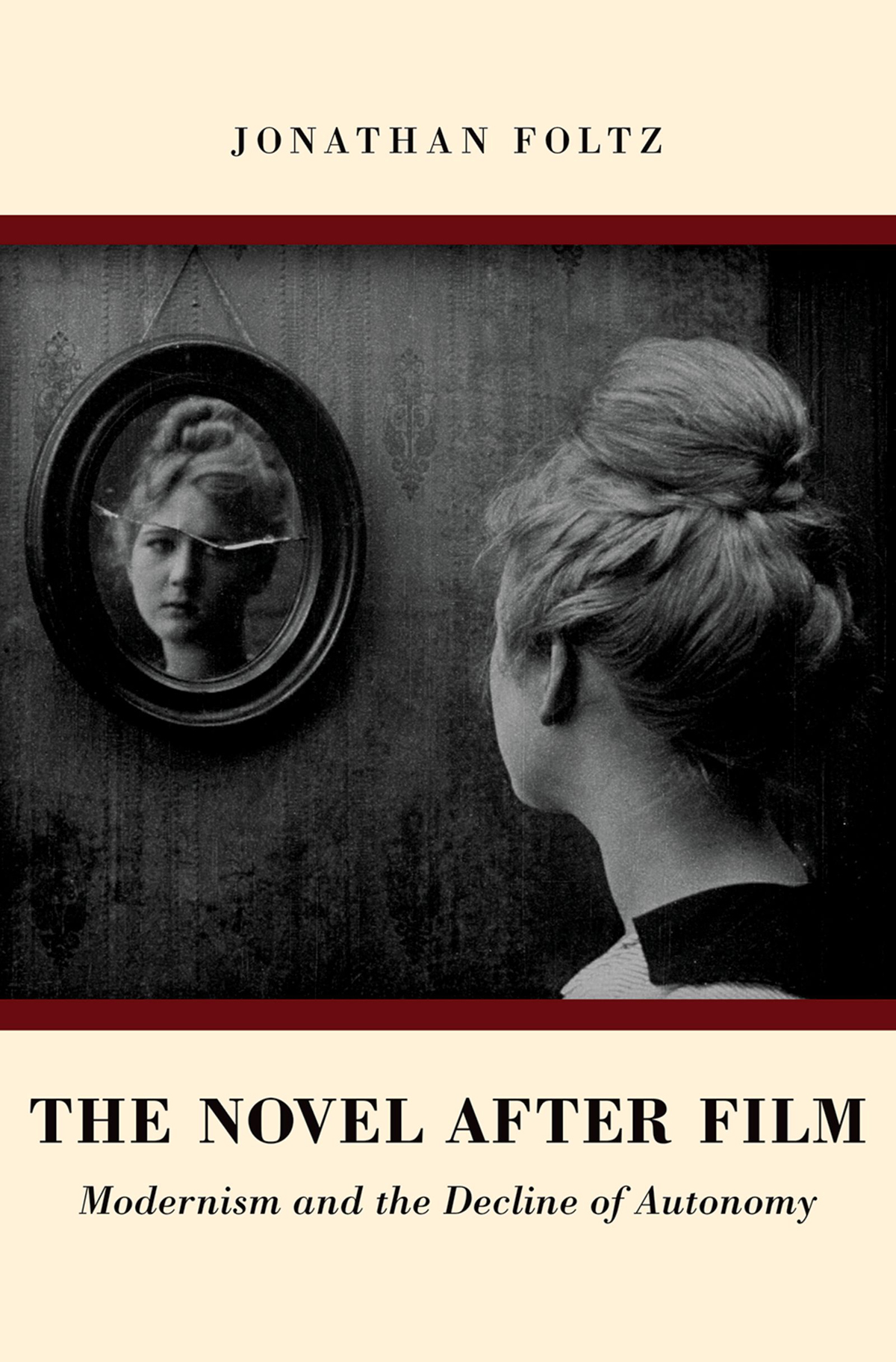

The Novel after Film

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

Oxford University Press 2018

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Foltz, Jonathan, author.

Title: The novel after film : modernism and the decline of autonomy /

Jonathan Foltz.

Description: New York : Oxford University Press, 2018. | Includes

bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017010325 | ISBN 9780190676490 (hardback) | ISBN

9780190676513 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: FictionHistory and criticismTheory, etc. | Motion

picturesInfluence. | Modernism (Literature) | Criticism.

Classification: LCC PN3331 .F65 2018 | DDC 809.3dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017010325

Man rejoices in an incomparable faculty for presently mutilating and disfiguring any plaything that has helped create for him the illusion of leisure; nevertheless, so long as life retains its power of projecting itself upon his imagination, he will find the novel work of the impression better than anything he knows. Anything better for the purpose has assuredly yet to be discovered. He will give it up only when life itself too thoroughly disagrees with him. Even then, indeed, may fiction not find a second wind, or a fiftieth, in the very portrayal of that collapse? Till the world is an unpeopled void there will be an image in the mirror.

Henry James, The Future of the Novel (1899)

What I want to do is write. Thats why I watch movies.

Carol, dir. Todd Haynes (2015)

CONTENTS

These dear castoff pages cost me, and brought me, many splendid hours of frenzy and insight. I could not have withstood them or seen them through without a supporting crowd of friends, scholars, and colleagues.

Over fifteen years ago, back in the woods of Annandale, Geoff Sanborn and Nancy Leonard inspired me to see conceptual drama in the rhythm of a sentence; John Pruitt sensitized me to the formal dimensions of the moving image; and Daniel Berthold gracefully embodied the gravity of thought. I still hear their voices in my thinking, and find myself still working to live up to them.

At Princeton, I was blessed with an incredible set of advisors. In Eduardo Cadava, I found a mentor of uncommon insight and generosity, willing to see what I could not in my work. The wise light of his eloquence has been a constant beacon. Michael Wood was the best kind of interlocutor, guiding me in the nuance and rigors of talk. Our conversations were rarely about what we had planned, and in this he showed me that digression has its own philosophy. I am still responding to him. Jean-Michel Rabat offered his gracious counsel; his ready wit and effortless wisdom helped me see what professional poise looks like.

In more recent years, at Boston University, I have been lucky to find a wealth of welcoming colleagues who have guided me and helped me refine my work: John Paul Riquelme, Carrie Preston, Anna Henchman, Susan Mizruchi, Hunt Howell, Jack Matthews, Sanjay Krishnan, Bonnie Costello, Lee Monk, Roy Grundmann, Michael Prince, James Winn, Bill Loizeaux, and Minou Arjomand. In Boston and well before, Joe Rezek has been an extraordinary friend and a generous reader. Thanks are likewise due to Evan Kindley, Rob Lehman, Audrey Wasser, Maureen Chun, Sarah Keller, Theo Davis, Wendy Lee, Masha Mimran, Michelle Coghlan, Rachel Galvin, Jacky Shin, and (especially) I. Glendenning for their comments and conversation. They have all left their traces in these pages. During my sojourns in Sydney I was welcomed at the Centre for Modernism Studies, and I remain greatly indebted to Julian Murphet, Sarah Gleeson-White, Sean Pryor, and many others for their many insights as this project matured.

At many latitudes and over many years, Armando Mastrogiovanni has graced me with his friendship and his wealth of provocation, just as Nicholaus Patnaude has dazed me with his metaphors and his open heart. Nanda Golden, with his rhetorical flourish, has ever been my coconspirator.

A fellowship from the Boston University Center for the Humanities allowed me to finish this project at a key moment of its development, and I am indebted to the participants in the fellows seminar for their valuable feedback. I received crucial research support from the Huntington Library, where a dynamic group of scholars made significant contributions to my thinking. I am likewise grateful to the staff, librarians, and archivists at the Houghton Special Collections at Harvard; the Department of Rare Books and Special Collections at Princeton; the Library Special Collections at UCLA; the Harry Ransom Center at UT Austin; the British Library; Dennis Doros at Milestone Films; and Ruth Cahir at British Path for helping me access many of the documents and images that I consulted during my research. Portions of chapter 3 previously appeared in Modernism/modernity, and I am grateful to the editors for allowing me to reprint them here.

It has been said that the essence of cinema is contained in the image of wind blowing through trees. Here I must pay my respect to all the trees outside all the windows behind which I sat typing and thinking. Their dappled light, their raised and lowered leaves and branches have stirred green agitations in my thought, occasionally reminding me of what it was I had to answer to.

Finally, I would like to thank my family for what cannot be thanked, for their endless encouragement, their understanding, their faith and their love. My father, the videographer, first tutored me in the secret languages of the image. My mother, a true teacher of teachers, nurtured my instincts to learn before I knew what they were. Whatever is good in this book, or in me, began with them. Yet it could not have been completed without the enlarging love of my wife, Anna Vinnik. She has been my finest reader and the warmest witness. All my thoughts, on the page and off, have been brightened absurdly by her smile and by the infectious music of her company.

The Novel after Film

THE NOVEL AFTER FILM

) you may catch sight of an anxious second cameraman rushing back behind the crowd of mourners to get a better angle on the scene.

In the morbid comedy of this story about the death of an author we can register the familiar outlines of what was, in the 1920s, still a fresh anxiety: that arts, like artists, also have a lifespan, and that, in the swell of modern inventions, the era of the novel, of observation informed by a living heart, was now on the verge of being rudely displaced by a mode of observation that conspicuously lacked one. Yet we do not need to accept as historical the rather panicked idea that film rendered the traditional novel obsolete. The oft-told fables about the impending death or supersession of the novel, with the requisite camera men in attendance, are important fixtures of our current mythology of literary history, but their importance does not stem primarily from their accuracy.