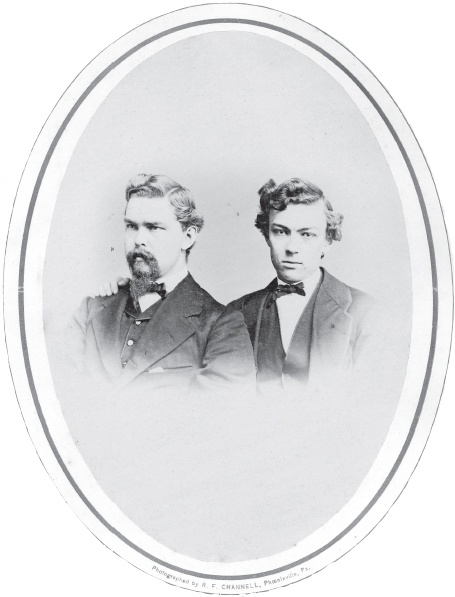

Frontispiece: Singleton M. Ashenfelter and Samuel W. Pennypacker (Courtesy

of Pennypacker Mills, County of Montgomery, Schwenksville, PA)

2019 by The Kent State University Press

All rights reserved

ISBN 978-1-60635-383-7

Manufactured in the United States of America

No part of this book may be used or reproduced, in any manner whatsoever, without written permission from the Publisher, except in the case of short quotations in critical reviews or articles.

Cataloging information for this title is available at the Library of Congress.

23 22 21 20 19 5 4 3 2 1

Frontispiece. Singleton M. Ashenfelter and Samuel W. Pennypacker

THOSE OF US WHO STUDY THE CIVIL WAR, AND ESPECIALLY THE CIVIL War home front, love to wade into wartime diaries and letters. This is particularly true for historians who focus on life in the North. Civilians who wrote letters left us an invaluable account of a nation at war. Some correspondents penned long discussions of what they thought about the war. They wrote details about particular events; they recorded personal opinions about particular battles and campaigns; they captured immediate responses to conflicts and celebrations in their own communities. Others only mentioned the wars military and political narrative on rare occasions, providing the historian with a useful quote here and there. While this is partially just a reflection of what people chose to write about in their letters, it also illustrates a larger truth: in the Civil War North, many aspects of life carried on almost undisturbed by events on distant battlefields. Such was the reality of the Northern home front.

The wartime letters of Singleton Ashenfelter, a student at Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, are a great source about mid-nineteenth century America, particularly the Civil War home front. Readers looking for commentary on the war as a military and political struggle will find very few nuggets within this correspondence. In a broader sense one might argue that Ashenfelters relative silence about such major events is in fact an eloquent commentary about the role of the national conflict in the daily lives of at least some civilians at home. If Ashenfelterwho was a young man during the warwas deeply concerned about the details of the conflict, he did not let those concerns sneak into his correspondence very often. Occasionally, one finds a comment on events important to the Civil War narrative. He wrote some useful letters about antiwar Democrats (he disliked them) and had a bit to say about the Army of Northern Virginias 1862 invasion of Maryland, which culminated in the Battle of Antietam (on September 17). But the truth is that, day in and day out, Singleton Ashenfelter devoted his fascinating letters to his own life and thoughts. And as a chronicler of such, he has provided the historian with invaluable information about a host of fairly elusive topics.

Let me suggest a few.

Ashenfelters letters offer a marvelous window into the daily life of the mid-nineteenth-century college student. Historians have just begun to explore the collegiate worlds in both the North and the South. Some have asked questions about the impact of the Civil War on students lives, while others have looked more broadly at the role of colleges and universities in shaping men and society. Ashenfelters letters are rich with the quotidian details of a young mans world in these institutions. We learn about the rules that defined a mans life at Dickinson and the discipline that transgressors faced. Ashenfelter, who would describe himself as a good fellow more than a good student, threw himself into club life and literary societies, even being tabbed to deliver a major address on Religious Liberty. On occasion he got drawn into college hijinks, including one occasion when he posted a series of anonymous parodies on a Dickinson bulletin board, earning himself a bit of notoriety among his peers. Such accounts are priceless windows into wartime college life. Along the way we learn quite a bit about what Ashenfelter read and admired, about his classes, and about his thoughts on various teachers, authors, and ideas.

These comments about college life are interspersed with a wealth of information about the thoughts and personal preoccupations of a young man in midcentury America. In truth, many Civil Warera menboth at home or in uniformwere quite introspective about large ideas. But the range of topics that absorbed Ashenfelters thoughts, not to mention the depth of his writings, is distinctive, even when the topics themselves are familiar. As a college student, Ashenfelter developed a strong affection for alcohol, an issue he periodically confronted and attempted to limit. Like many other young men, he wrestled with both religion and his own vices. Concluding that he could not believe in any Deity, he nevertheless devoted many pages to discussions of organized religion. Looking in the mirror, Ashenfelter often seemed to find himself wanting, worried about his selfishness and sloth as well as his drinking and other misbehaviors. (He devotes one long paragraph to his unfortunate habit of swearing.) And, like many other young men, Ashenfelter expended much thought and energy on young women. In the space of just a few years, he managed to grow deeply attached to at least three women, providing plenty of details about courtship, while also perpetually questioning his own impulses and actions. But around the age of twenty, Ashenfelter seems to have settled on Annie Euen as the principle object of his substantial desires, providing interesting insights about both friendship and courtship between young men and women during this period.

These are just a few of the many topics that come up in these letters. Having myself read many dozens of collections of wartime letters and diaries, much of Ashenfelters introspection feels more like what one might find in a young mans diary, not in his correspondence with another man. If we step away from the individual passages and letters as bits of evidence and consider this book as a single fascinating document, it becomesI thinka wonderful source for two interconnected themes: the nature of midcentury masculinity, and the shape and character of friendships among men.

This book is at its core a portrait of the intense friendship between Singleton Ashenfelter and Samuel Pennypacker as viewed through the lens of Ashenfelters letters. Pennypacker was only a year older, but sometimes he seemed to adopt a mentor role. As the editors explain, the two men remained friends for a half century. This collection captures their relationship when they were still young, trying to navigate their futures.

These letters from Sing to Pennie include a surprising number of comments about the etiquette of correspondence and much more about the nature of friendship. Sing apologizes for being dilatory (February 12, 1863) in responding to Pennies most recent missive. This becomes a recurring theme as letters carefully dissect who owes the next letter, with Sing periodically chafing at gaps between incoming correspondence. In late November 1863 he writes an extremely long letter to Pennie, confessing his loneliness at Dickinson and admitting, I miss most just such a friend as I feel you to be. The college continued to provide pleasant distractions, but no friend had emerged on campus who could match the pleasures he enjoyed with Pennie. In this long letter Sing takes a lengthy digression to describe a classmate named Jackson, who he feels is a true genius. I am so deeply interested in this Jackson that I could not refrain from telling you of him, he admits. But it becomes clear that Sing is seeking not merely a kindred spirit in Jackson but a replacement for Pennie. When I think of how often I would write to you if I only owed you a letter, he writes, I feel as if I would like it better were we to drop all formality & write just when we feel inclined; without reference to answered or unanswered letters. Would such a correspondence suit you, he wondered (November 22, 1863). The following May Sing returns to these themes, declaring, I wish I could find words to express my intense loneliness. I am not homesick, but friendsick. Having defined his classmate Jackson as an intriguing genius, Sing takes pains to describe Sam (Pennypacker) as a genius too in several subsequent letters.

KENT, OHIO

KENT, OHIO