Copyright 2004 by Peter Kenez

Originally published as Civil War in South Russia 1918 , 1971

by the Regents of the University of California

First edition by New Academia Publishing, 2004

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2004109650

ISBN 0-9744934-4-9 paperback

| New Academia Publishing P.O. Box 27420, Washington, DC 20038-7420 |

to Dorothy J. Dalby

with Admiration and Affection

Acknowledgments

I am most grateful for the help I received from a number of colleagues. Mr. Hans J. Rogger pointed out to me a large number of major and minor errors and advised me in matters of organization of the material; Mr. William G. Rosenberg read an early version of the manuscript and discussions with him helped me to clarify my thinking on a number of points; Mr. Terence Emmons read the galley proofs and caught some mistakes; Mr. William H. Hill compiled the index.

Within the walls of two major archives I worked inthe Russian and Eastern European Archives of Columbia University, and the Hoover Institution at Stanford, CaliforniaI was helped with understanding and kindness. I am especially grateful to Mr. Lev F. Magerovsky, who provided me with much-needed material and gave me useful biographical and bibliographical information. Mrs. Xenia Denikin and Mrs. Olga Wrangel allowed me to use their husbands archives. It was both useful and pleasant to listen to Mrs. Denikins reminiscences.

In my research and writing I was supported by the History Department of Harvard University, the Research Committee of the University of California at Santa Cruz, and the Slavic Center of the University of California at Berkeley.

I should like to thank Mrs. Eveline Kanes and Mrs. Dorothy J. Dalby, who corrected many of my grammatical errors and suggested improvements in my writing style. I also thank Miss Jacqueline Crisp, who checked several references, and Miss Jeanine Thompson, who typed the manuscript.

All dates are given according to the Gregorian or Western calendar, except as noted in a few quotations. I have followed the transliteration system of the Library of Congress.

P.K.

Introduction

The best book on the Russian Civil War, William Henry Chamberlins The Russian Revolution, was published in 1935. That this relatively short study has remained unsurpassed for over three decades, while Russian studies were expanding enormously, shows that the Civil War has received little attention from historians outside the borders of the Soviet Union.

The subject is immensely important. The Soviet Union was created as much by the Civil War as by the revolutions of 1917; indeed, the revolutions and the struggle that followed are inseparable. At the end of 1917, few people knew who the Bolsheviks were and what they wanted, and even Lenin and his followers could not have had very clear ideas about the nature of their future system; it was only in the long and merciless war that the foundations of the Soviet regime were laid. Perhaps Russian Communism would have evolved differently had the bitter necessities of the Civil War not forced the regime to develop some features that had nothing to do with Marxist ideology.

Aside from the obvious historical significance of the Civil War, it is also a subject with great intrinsic interest. The country fell apart and almost every village had its own Civil War, sometimes focused on issues that were unrelated to the ideology of either Whites or Reds. A large variety of socialist and conservative ideologies, mutually exclusive nationalistic claims of people living in the territory of the Russian empire, foreign interventionall of these had a role in deciding the final outcome. In this period of confusion political institutions collapsed, the values of a civilized society almost disappeared, and in some respects the country reverted to a state of fragmentation that had existed several centuries before. Modern European history provides no better example of anarchy and its effects on social institutions and human beings.

The complexity of the Civil War, which makes it a fascinating subject, also makes it a difficult one for historical study. In all likelihood this difficulty is the primary cause for its neglect by Western historians. A comprehensive survey of the Civil War can hardly be undertaken until a number of detailed studies of limited areas and periods have been made. Only in such works can adequate attention be given to all or most of the important forces operating in any one area. Extrapolating from one part of Russia to the entire enormous country is perhaps the best way to become aware of the many different issues that were at stake, and of the difficulty of reducing the problems of the Civil War to simple formulae.

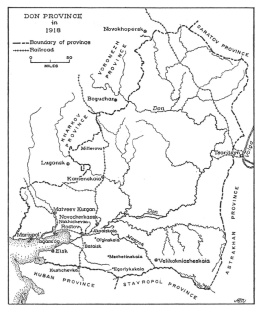

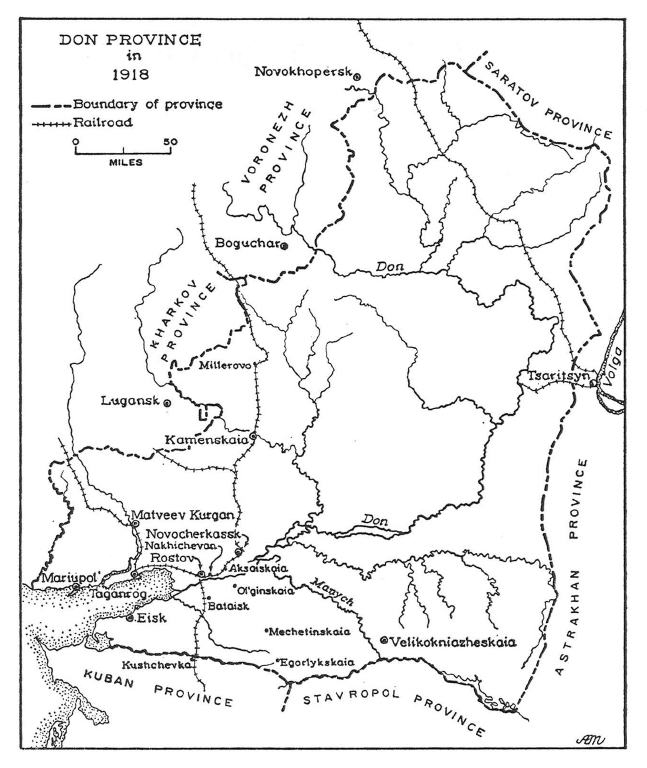

South Russia is a particularly good subject for a case study, because it was a microcosm in which one can see most of the ills of Russia, and because of the intrinsic importance of the events that took place there. It was there that the Civil War began and ended, there that the Whites put their most substantial and persistent armies into the field. In this area foreign intervention assumed greater importance than elsewhere; and perhaps nowhere else did the anti-Bolshevik movement suffer more from dissension and the competing claims of national minorities.

The outcome of the Civil War in South Russia, as in other sections, was decided by the struggle of a combination of local and national forces. The aim of the present study is to analyze these forces and their relationships to each other.

The chief actors of the drama were the ex-imperial officers who came to the Don and the Kuban to take arms against Lenins regime. For them the choice of a theater of operations was largely accidental; their thoughts were centered on Moscow and Petrograd. (For example, after a stay of almost two years they continued to observe Petrograd, as opposed to local, time.) Who these officers were, how they came to decide to fight the Soviet regime, and how they envisaged Russias future are among the crucial questions of the Civil War.

The officers formed the general staff of the anti-Bolshevik movement, in both its concrete and its figurative senses. They played a role far out of proportion to their numbers; they provided military and political leadership, and they were a nucleus around which other anti-Soviet groups could unite. However, on their own they would have been impotent. No matter how heroic and determined these few thousand men were, the Bolsheviks would have crushed them without difficulty. From the summer of 1918 on, the overwhelming majority of the White army was made up of Cossacks. The Cossacks cared little about the rest of Russia; for them the Civil War was a struggle against the non-Cossack peasants, the so-called inogorodnye , who looked covetously at Cossack lands. Only a partial coincidence of interests existed between officers and Cossacks, and the two groups never understood each other. Consideration of the differences in views within the White camp, and of local circumstances, is essential to an understanding of the Civil War.