Copyright 2004 by Peter Kenez

Originally published as Civil War in South Russia 19191920,

1977 by the Regents of the University of California

First edition by New Academia Publishing, 2004

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2004109651

ISBN 0-9744934-5-7 paperback

| New Academia Publishing PO Box 27420, Washington, DC 20038-7420 |

Acknowledgments

Several friends helped me in my work. William Rosenberg, Barbara Clements and David Joravsky read the entire manuscript, and on the basis of their suggestions I made many improvements. William Rosenberg also called my attention to materials which I had overlooked. Isebill Gruhn, Victoria Bonnell and George Baer read various chapters. Discussions with them were useful in clarifying my thinking on a number of points and I am grateful to them for their friendship and encouragement.

In my research and writing I was supported by the Hoover Institution which twice awarded me National Fellowships, first for the summer of 1972 and then for the academic year of 1973-1974. The Hoover Institution provided me not only with a magnificent library and rich archives, but also with ideal working conditions. I enjoyed the company of my fellow National Fellows. The Research Committee of the Academic Senate of the University of California at Santa Cruz awarded me several grants. These grants enabled me to travel to New York twice and work in the Archives of the Russian and Eastern European Institute of Columbia University.

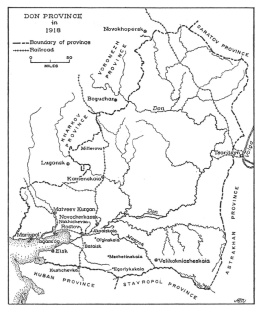

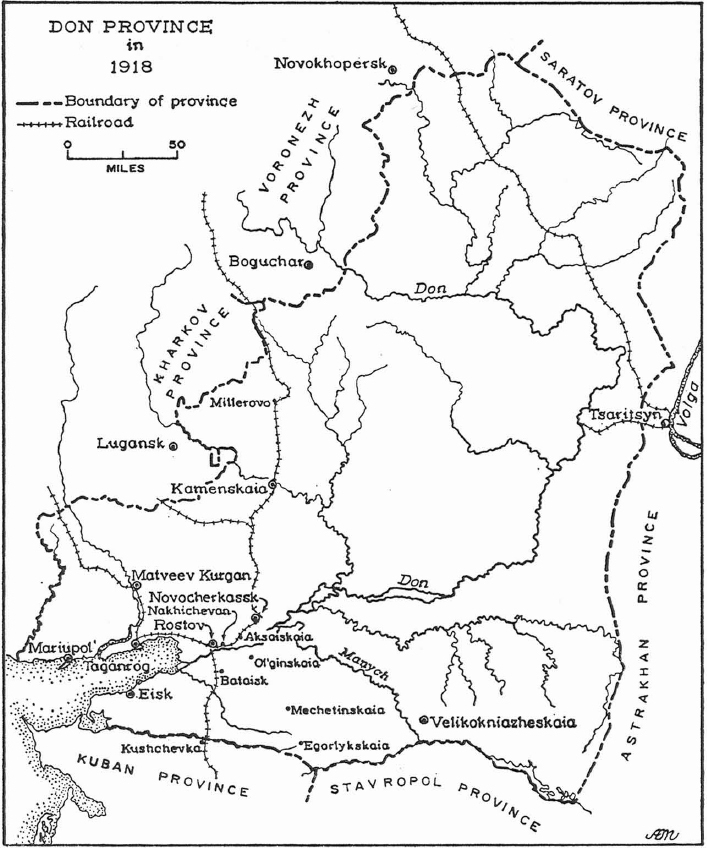

I would also like to thank Dorothy Dalby, who corrected many of my grammatical errors, Gene Tanke, whose copy editing greatly improved the final text, Lynn Mally, who prepared the index and Adrienne Morgan, who drew the maps.

Sections of this book have appeared in Slavonic and Eastern European Journal, The Russian Review and The Wiener Library Bulletin.

All dates are given according to the Gregorian or Western calendar, unless otherwise indicated. I have followed the transliteration system of the Library of Congress.

P.K.

Introduction

Every book on the Russian Civil War is essentially a study of the causes of the victors victory and the losers defeat. Even the historian who aims at nothing more than telling the story of the struggle at least implicitly provides us with an explanation of the outcome.

In Western historiography there is general agreement on the main causes of Bolshevik victory, and most historians would agree with the following summary. The Bolsheviks possessed superior leadership. Lenin was a master of political strategy and Trotskii had great organizational ability, which he showed in creating the Red Army and leading it to victory. The Bolsheviks also took advantage of the revolutionary enthusiasm of the Russian people, an enthusiasm fired by the injustices they had suffered under an outdated political and social system; the crucible of a modern war revealed just how outdated it was. Lenins appropriation of the agrarian program of the Social Revolutionaries induced the peasants to prefer the Bolsheviks to their enemies. And whereas the Bolsheviks were relatively united, their enemies were divided by personal animosities, ideologies, and memories of previous conflicts. The Bolsheviks, who occupied the center of the country, had a great strategic advantage: their enemies had to base their movements on the peripheries, inhabited largely by non-Russians; the Red Army could send reinforcements to any segment of the front that was most directly threatened, but the Whites could not coordinate their military moves.

But such a simple enumeration of causes is hardly satisfactory. After all, what evidence do we have, for instance, that the peasants preferred the Bolsheviks, except the fact that the Bolsheviks ultimately won? Besides, is it not possible that the Bolsheviks won in spite of the attitude of the peasants? How is one to balance the importance of the favorable strategic position of the Bolsheviks against the significance of Allied aid, which obviously greatly benefited the Whites? It is true that the anti-Bolshevik camp was deeply divided, but perhaps the White advantage of having a large pool of experienced administrators and trained officers was an adequate compensation. Most important, how is one to rank the various explanations? Which cause should we consider primary?

This book, too, is an attempt to explain the outcome of the Civil War. However, I will try to develop a primary or general explanation for the defeat of the Whites, one broad enough to include a number of the others previously mentioned. In the process of describing the defeat of the Whites I hope to work out a new framework for looking at the Civil War. Instead of regarding it as a purely military contest between two opposing armies, I will approach it as a political competition between the two major antagonists in which each tried to impose its will on a reluctant people. The winner in this competition was the winner of the Civil War.

The Revolution represented the disintegration of traditional authority. The institutions, the ideology, and the leaders by which the tsarist regime governed the country at the time of an extremely demanding war proved inadequate. The March revolution gave an opportunity to the liberal intelligentsia to experiment with a new system, but the events of 1917 proved conclusively that the Provisional Government was no more able to hold the country together than its defunct predecessor. The victorious liberals not only failed to reverse the process of disintegration, but themselves contributed to anarchy. Under the circumstances, the accomplishment of the Bolsheviks in November was a slight one. Almost any small group of determined men with some support from the people could have removed the defenseless Provisional Government, which had already defeated itself. The difficult task lay ahead: the Bolsheviks had to devise a system of government which could cope with the extraordinary situation.

The Civil War was a period of boundless anarchy; but it was also a time when groups of men experimented with institutions and ideologies which would help them to overcome anarchy. One might have thought that the democratic socialists, whose program was clearly favored by a majority of Russians, would have had the best chance of rallying the people. Yet within a year the Socialist Revo lutionaries and the Mensheviks had lost all positions of power and influence, proving that an attractive ideology is only one component for establishing a successful government. Most socialists drew the unavoidable conclusions and, depending on their ideologies and personalities, joined either the Whites or the Reds, the two surviving antagonists.