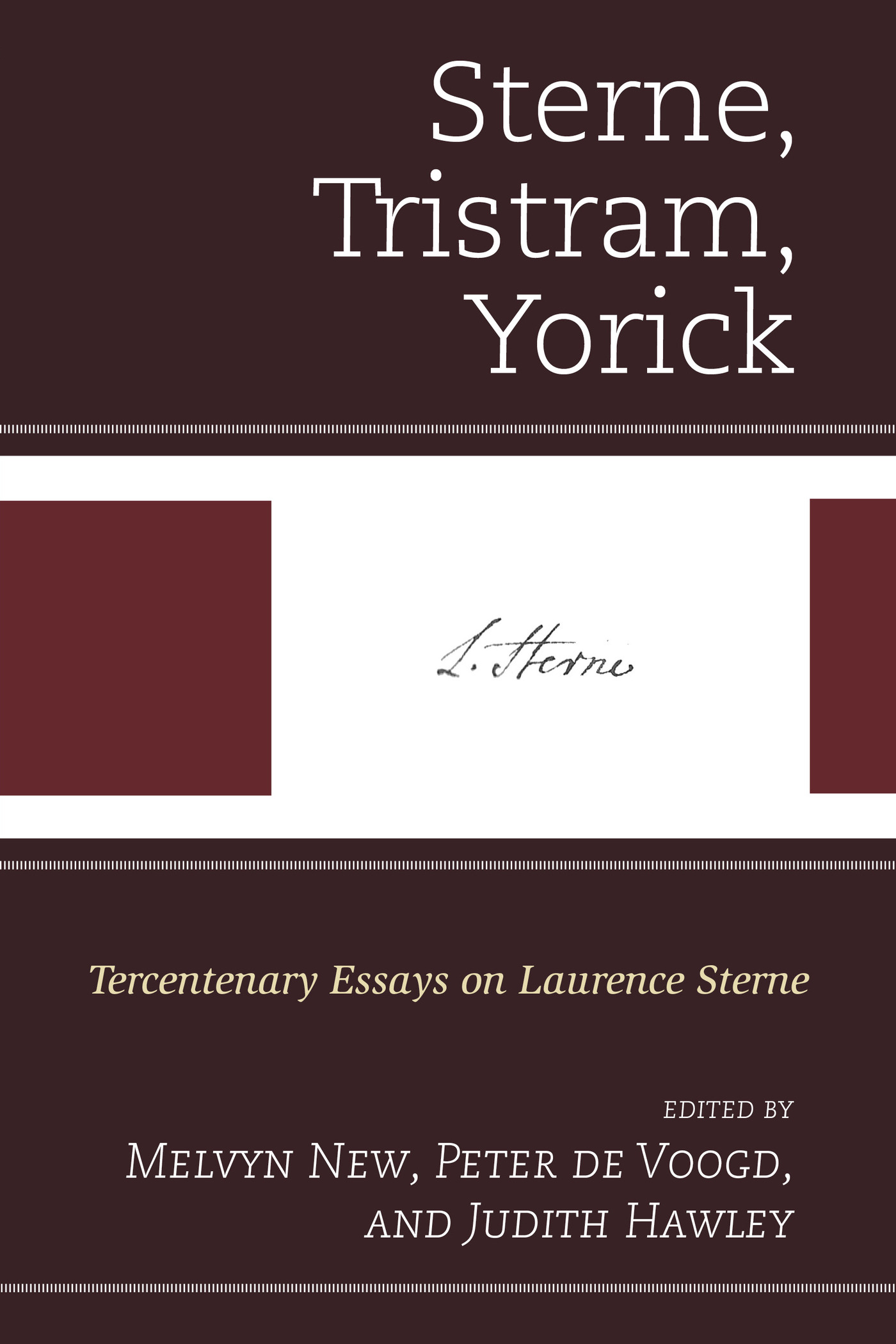

Sterne, Tristram, Yorick

Sterne, Tristram, Yorick

Tercentenary Essays on Laurence Sterne

Edited by Melvyn New,

Peter de Voogd, and Judith Hawley

UNIVERSITY OF DELAWARE PRESS

Newark

Published by University of Delaware Press

Copublished by The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.rowman.com

Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB

Copyright 2016 by Rowman & Littlefield

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Sterne, Tristram, Yorick : tercentenary essays on Laurence Sterne / edited by Peter de Voogd, Judith Hawley, and Melvyn New.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-61149-570-6 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-61149-571-3 (ebook)

1. Sterne, Laurence, 1713-1768Criticism and interpretation. 2. Sterne, Laurence, 1713-1768Appreciation. I. Voogd, Peter Jan de, editor. II. Hawley, Judith, editor. III. New, Melvyn, editor.

PR3716.S845 2016

823'.6dc23

2015027989

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

Introduction

Pat Rogers

This volume derives from the Laurence Sterne Tercentenary Conference, held at Royal Holloway, University of London, on July 811, 2013. Attended by some eighty scholars from fourteen countries, the conference heard more than sixty papers, along with three plenary lectures and a brilliant one-man performance of Tristram Shandy by Stephen Oxley. The organizers of the conference invited participants to submit revised versions of their contributions for this collection, and they have selected thirteen essays that they hope exhibit some of the defining features both of the conference and of Sterne studies at this moment. It is worth remarking that the authors selected represent seven countries; that Sterne may well be the most internationally accepted of all eighteenth-century authors is certainly a claim worthy of a sentimental traveler. Some additional essays from the conference have appeared in volumes 24 and 25 of the Shandean (2013, 2014). Melvyn News plenary address, originally intended as a coda to this volume, will appear in volume 26 (2015) of the Shandean.

***

The progress of this field of inquiry has been jagged. In the authors lifetime, and for some time afterward, debate often focused on what later seemed to be slight or irrelevant issues, with much attention inevitably allotted to Sterne as a scandalous celebritythe macaroni parsonor to teasing out the mysteries surrounding plagiarized and pseudo-Shandean works. (Some of these matters have begun to surface for reexamination in modern times.) In the Romantic era, despite the admiration of Robert Burns and others, Sternes writing tended to appear as both obscene and flippant. Coleridge was not alone in deploring the affectation that blunted Sternes virtues as an author. One exception to such criticism is William Hazlitts brief but enthusiastic appraisal in his Lectures on the English Comic Writers. A more typical response from the period is that of Isaac DIsraeli (echoing a notorious assertion by Samuel Johnson in 1776): Cervantes is immortalRabelais and Sterne have passed away to the curious. American responses, at least those from puritan New England, were often negative. Thus a contributor to a Boston magazine in 1802 was able to state bluntly: I suppose few writers have done more injury to morals than Sterne. Many readers must have continued to know the books, chiefly mediated through selections such as the bowdlerized Beauties of Sterne. Meanwhile, the translations of Tristram Shandy and A Sentimental Journey that quickly appeared in French, German, and Dutch prompted thoughtful commentary, even though Germaine de Stal believed that Tristram Shandy loses almost all its charm in French. Critics were, however, able to detect an influence from Journey in Goethes Sorrows of Werther, one perhaps less apparent to modern eyes. Around the same time, Jean-Paul Richter evolved his own form of Shandyism (perhaps more accurately Yorickism), a blend of poetic afflatus, irony, fantasy, and self-scrutiny. The most noteworthy Italian rendition of Journey was that of Ugo Foscolo in 1813, accompanied by an acute recognition, for once, of the satiric bent of the novel. Foscolo had retraced many of Yoricks wanderings while serving in Napoleons army, a curious historical juxtaposition.

The Victorian era saw some advances in knowledge about Sterne, if not too much by way of a deeper understanding of his art. The most widely known, damning assessment is that of W. M. Thackeray, in his English Humourists of the Eighteenth Century (1864). Notoriously, Thackeray alleged that Sterne used to blubber perpetually in his study, hardly something that would consort well with males brought up on Tom Browns Schooldays and the cult of muscular Christianity. He went on to assert, in a much quoted passage, [Sterne] is always looking in my face, watching his effect, uncertain whether I think him an impostor or not; posture-making, coaxing, and imploring me. Unsurprising, then, that the main line of nineteenth-century fiction, constructed as the great tradition, would have little use for Sterne. An approach that valued above all else the moral seriousness of George Eliot and Henry James would automatically regard Tristram Shandy as a mere sport, springing up in an untended corner of the literary garden, and having no place among the carefully cultivated prize blooms. At the same time the antiquarians got to work and began to uncover more of the myriad sources of Tristram, bringing with this pursuit a better sense of the eclectic nature of the text, dependent as it is on Robert Burtons Anatomy of Melancholy in addition to Rabelais, Shakespeare, Montaigne, Cervantes, and Swift. By the end of the century, Sterne had recovered some ground. He earned a place in the English Men of Letters series in 1882, with a volume by H. D. Traill that contains some halfway decent observations. George Saintsbury, one of the most influential critics of the day, thought it worth putting his name to a six-volume edition of the Works in 1894, while his introductions to the two main works, plus the recently discovered Journal to Eliza (or Bramines Journal, as in the modern edition), which appeared in the Everyman series, almost certainly reached more readers than any previous commentary of this kind.

The letters to Eliza had surfaced a number of years earlier and were first edited by Wilbur L. Cross in 1904, one part of his twelve-volume edition of Sternes works that served scholars well for almost the entire century. Cross (18621946), a professor and dean at Yale, ended up as governor of Connecticut for two terms in the 1930s, and has been commemorated by a parkway in his home state. He may be said to have laid the foundations for modern scholarship with his edition and by virtue of his biography,

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.