Copyright 1993 by Marie G. Lee

All rights reserved.

CW: There are scenes in this book that depict the use of racial slurs.

This is a work of f iction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the authors imagination or are used f ictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, businesses, companies, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

This edition first published in 2020 by

Soho Press, Inc.

227 W 17th Street

New York, NY 10011

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Lee, Marie G., author.

Title: Finding my voice / Marie Myung-Ok Lee.

Description: New York, NY : Soho Teen, 2020. | Originally published : Boston : Houghton Mifflin, 1992. | Identifiers: LCCN 2020008600

ISBN 978-1-64129-197-2

eISBN 978-1-64129-198-9

Subjects: LCSH: Korean AmericansJuvenile fiction. | CYAC: Korean

AmericansFiction. | High schoolsFiction. | SchoolsFiction.

Parent and childFiction. | College choiceFiction. | PrejudicesFiction.

Classification: LCC PZ7.L5138 Fi 2020 | DDC [Fic]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020008600

Interior art: ElenaMedvedeva/iStock

Interior design by Janine Agro, Soho Press, Inc.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To Mom and in memory of Papa

Foreword

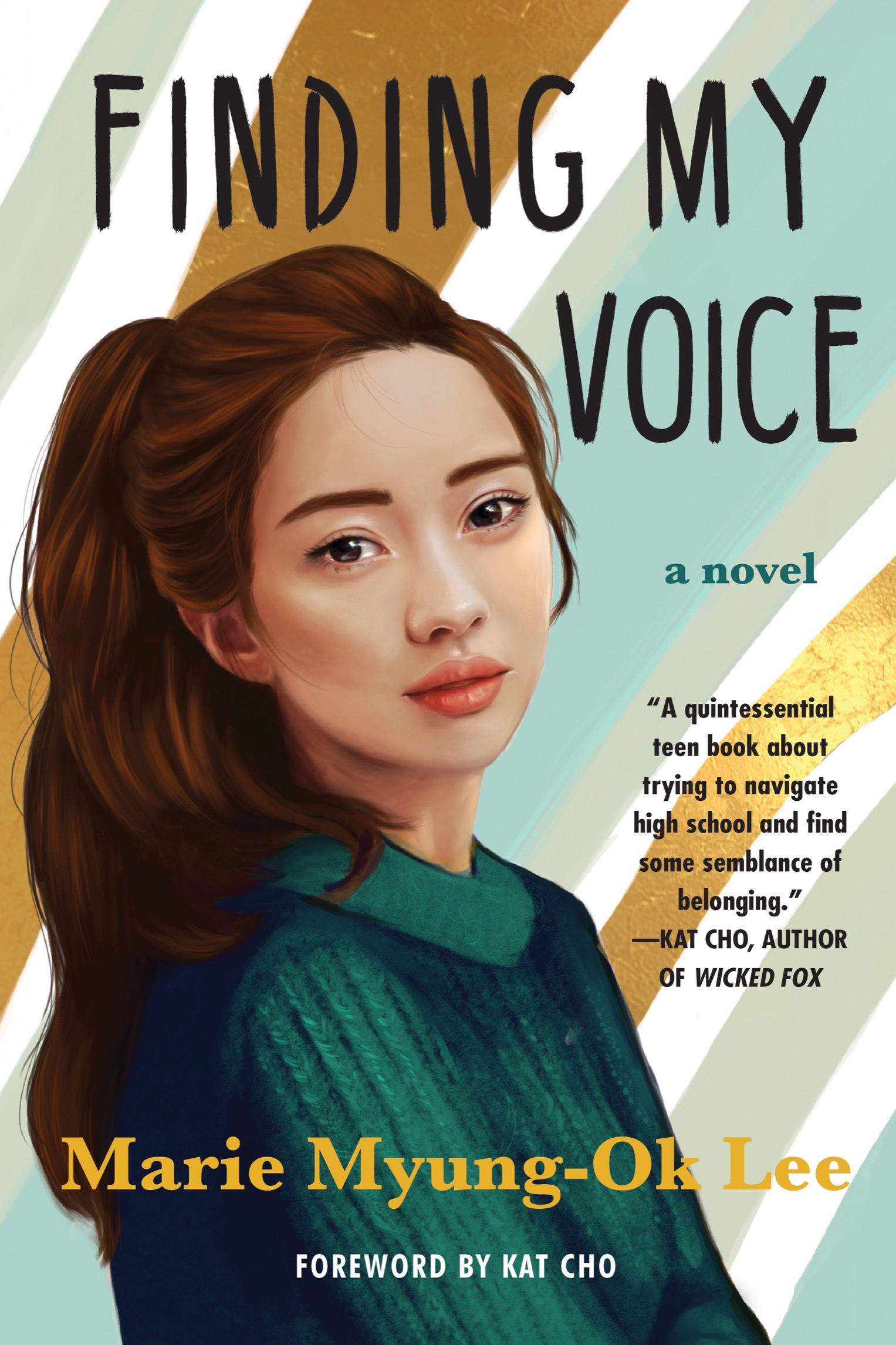

F inding My Voice perfectly captures that diasporic in-between feeling when you know that you dont quite fit in with your immigrant parents view of your life, but you also dont fit in with your peers at school. It navigates the rocky terrain of trying to brush off microaggressions in the form of off-color jokes from bullies and classmates and even teachers in a position of authority. This book encapsulates that hard-to-describe feeling of having so many similarities to your peers, but feeling like the unavoidable fact of your heritage sets you ever so slightly apart no matter how much you try to blend in. At the same time, Finding My Voice is a quintessential teen book about trying to navigate high school and find some semblance of belonging that is a universal teen struggle. Noticing how the homecoming court is a popularity contest or that some people seem to rise above with such little effort while the majority of us were struggling to tread the deep waters that are teenage angst.

I am so happy that Finding My Voice is finding new life for a whole new generation of readers. And I am sad. Because I never found this book in my formative years when it was so hard to put words to how othered I felt in my everyday life. Whenever my friends made jokes about my Koreanness, I laughed it off because I didnt want to kill the mood. Whenever my parents had higher expectations of me because I had to be three times better than my white peers to get exactly the same thing, I thought it was so unfair but I had no way to explain that feeling to parents whod struggled through much harder times than I did. I wish Id had Ellen to guide me through those hard feelings when I was a teen. Which is why Im so glad that so many Korean and Asian-American teens will have her now.

Kat Cho

Moooo! It is still dark when I reach to shut off the Holstein-shaped alarm clock that my best friend, Jessie, gave me for my sixteenth birthday. To shut it off, you have to pull down on the cows enormous plastic udder. Mom wanted to throw it out. I told her it was just humor, Jessie-style.

I step into the steamy shower and let the warmth coax me awake. I shampoo, shave my legs, and let the conditioner sit in my hair for exactly five minutes, just as it says on the bottle. After toweling off, I put on deodorant, foot powder, perfume, and then begin applying wine-colored eyeliner under my lashes.

Do boys have to go through all this trouble day in and day out? How about Tomper Sandel, the football player who appears to be naturally cute with his shaggy blond hair and cleft chindoes he worry about how he smells?

I put on extra eye shadow in a semicircle around my top eyelid. According to Glamour magazine, this will give Oriental eyes a look of depth. Ive always known that I dont have the neat crease at the top of my lidlike my friends dothat tells you exactly where the eye shadow should stop. So every day I have to paint in that crease, but I dont think Im fooling anybody.

Hurry up, Ellen, Mom calls from downstairs. I throw on my new Ocean Pacific T-shirt and jeans and run down.

Mom is standing in the kitchen, quietly spreading peanut butter on whole wheat bread. She turns to look at me, and her eyebrows dip into a slight frown.

Is that what youre wearing to school?

Yes, Mom, I say. We go through this scene every year.

What about all those good clothes we bought in Minneapolis?

Those dresses are great, I say. But no one wears a dress on the first day of school.

Oh, Mom says, as if shes not convinced. She turns to finish packing my lunch. As usual, Father has already left for the hospital so he can get an early start on patients with morning-empty, surgery-ready stomachs.

I grab the Cheerios and milk, and eat while looking over my schedule one more time. This year, I wont have Jessie in a single class. She took typing and creative foods so that she can have more free time. In the meantime, Ill be sweating out calculus and trying to tack gymnastics onto my already-stuffed schedule. My parents say I have to take all the hard classes so I can get into Harvard like my sister, Michelle.

Heres your lunch, Mom says, handing me a brown paper bag. I open it and find a small container filled with soft white ovals in sugary liquid.

What is this? I grimace, holding the tiny container aloft. Litchi nuts, Mom answers. Remember? You love them.

Not for lunch, I say, a little too vehemently. The truth is, I dont want people seeing those foreign-looking nuts and asking what they are.

Then I remember that every day Mom packs Fathers lunch, then my lunch, while Im up in the bathroom doing my deodorant-perfume-powder dance.

Well, thanks, though, Mom, I say. Could I please have a Hersheys bar from now on?

Mom smiles. She is so thin and small in her gown and robe. I throw my lunch in my knapsack and kiss her quickly.

Goodbye, Myong-Ok. Its your last year here, she says. I look up at her upon hearing my Korean name. To me, it doesnt sound like my name, but to Mom, I think it means something special. Sometimes I think she has so much more to say to me, but it gets lost, partly because of the gap separating Korean and English, and partly because of some other kind of gap that has always existed between me and my parents.

On the way to the bus stop, I slip the container of litchi nuts into a garbage can alongside the road. Wasteful, I know, but Im always so nervous on the first day of school. All those kids. Especially the popular ones.

Everyone is at the bus stopthe same faces from last year, and the year before, and the year before that, but my throat still constricts. I wish Jessie lived nearby so she could take the bus with me. Two of the hockey players, Brad Whitlock and Mike Anderson, are loudly hooting and swaggering as if they own the place. I slip back and try to become invisible.

When the bus comes, student bodies swarm around the door like eager bees waiting to get into the hive. I let most of the kids go ahead of me, but as I board, someone shoves me from behind.

Hey, chink, move over.

In back of me is Brad Whitlock, a darkly adult look clouding his face. The sound of his words hangs for a moment in the cramped air of the school bus. Numbly, I look around. Everyone seems to be looking somewhere else: out the window, at their books, just away. Brad pushes past me to the back of the bus, where he resumes guffawing with his friends.