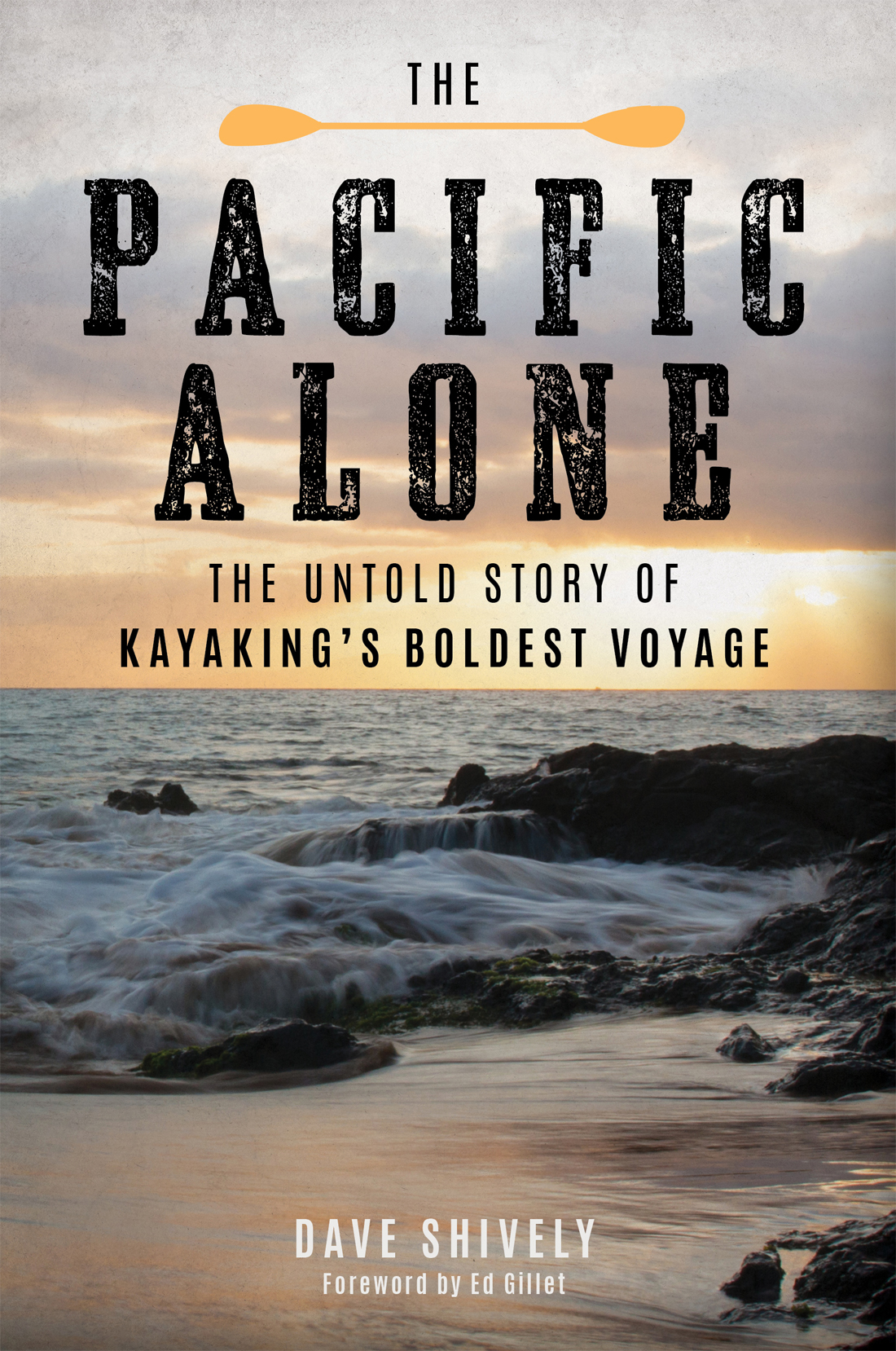

A BOUT THE A UTHOR

Dave Shively is a Colorado-bred, California-based journalist who serves as the Content Director for TEN: The Enthusiast Networks Paddles-ports Group. As the longtime managing editor of Canoe & Kayak and senior editor of SUP magazine, which he helped launch in 2009, Shively established a respected voice in the sport by grounding unique profiles and travel narratives in paddling experiences documented from Nunavut to New Orleans, and while tracking the rise of stand-up paddleboarding from fjords in Alaska to canals in Venice. Shively recently won Folios 2017 Single Article Eddie Award for Healing Waters ( Canoe & Kayak , Winter 2016), a series of veteran profiles exploring PTSD and the transformative power of the outdoors.

T HE P ACIFIC A LONE

An imprint of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Blvd., Ste. 200

Lanham, MD 20706

www.rowman.com

Falcon and FalconGuides are registered trademarks and Make Adventure Your Story is a trademark of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

Distributed by NATIONAL BOOK NETWORK

Copyright 2018 Dave Shively

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

ISBN 978-1-4930-2681-4 (hardcover)

ISBN 978-1-4930-2682-1 (e-book)

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

for Kristin

Foreword

The Pacific Alone is a well-chosen title, recalling the solitary and precarious nature of a trans-Pacific kayak voyage. But while I paddled my kayak alone, my wife, family, and dozens of active supportersa shadow crew of sortscame along in spirit. The emotional trauma of family and friends waiting for news of my arrival was real, and Dave Shivelys book skillfully weaves these disparate strandsthe angst of padding and waitinginto a coherent story. To enable him to tell this story well, I confided in Dave, trusting him with my journals and sharing my thoughts in a series of meetings beside the ocean, surf and sea breezes keeping the conversations real.

When I read The Pacific Alone , every word of Daves vivid retelling rang true, and I re-experienced the exhilaration and terror I felt when I was on that crossing. I was exquisitely aware that some accidental ship encounter, unexpected weather, a physical injury, any small mistake at all, might end in disaster or death. It was precisely that sense of edginess, though, that made my crossing worth doing. Now when I consider that state of being and read Daves accounts of other human-powered Pacific crossings, some successful and others tragic, I can only reflect on how fine a line exists between success and failure. Even though I lived this story, reading The Pacific Alone provided me with deeper insights into my sixty-four days of living on the edge.

Ed Gillet

San Diego

C HAPTER ONE

The Limit

1 23' 0.4" North, 78 50' 27.45" West

Pacific Ocean off the Ecuador-Colombia border

December 1984

T HE IDEA EMERGED FROM THE SWAMPY MANGROVE MUCK OF THE LAW less borderlands.

Ed Gillet paddled alone a under a half-moon. He followed the glowing V-shaped ripple ahead of his narrow kayaks bow. He kept the undulating point fixed on the dark lump of a distant island. Each stroke ahead flashed neon green as his paddle blades sparked small explosions of tiny bioluminescent reactions in the warm equatorial waters.

The sea was alive, Gillet recalled, noting sudden bursts as sea snakes would rise from the Pacifics depths, like lightning illuminating a thunderhead at night.

After such a strike, frenzied sardines would land by the dozen on the deck of the adventurers solo expedition sea kayakmuch less tense a matter than having to shoo the occasional sea snake off of the neoprene spraydeck covering his lap (used to keep water out of the boat). Gillet reveled in the dynamic surroundings and silence only broken by wild and abrupt interludes, the slap of acrobatic Mobula rays leaping and flapping furiously out of the water, or a flying fish smacking into his chest with the subtlety of a baseball thrown at close range.

Mainly though, he needed cooler paddling conditions, the night transit a means to avoid northwest Ecuadors debilitating midday heat. This crossing to Isla de la Plata, twenty-five miles offshore, would also provide a scenic detour in Gillets extended journey up the entire west coast of South America.

It also helped minimize unnecessary run-ins with local boatmen. Since leaving Chile, the locals seemed to be growing more suspicious and more aggressive in their interactions.

The sight of the lone paddler certainly posed more questions than answers. A nonmotorized boat was strange enough. An overloaded red sixteen-foot decked sliver of a craft, however, was another matter entirely. Especially one helmed by a tall, fair-skinned gringo whipping a succession of uninterrupted strokes across remote corners of the coast at a rapid clip, each twist of the torso bouncing a mangled lock of fiery blond hair.

Through Chile the conversations with local fishermen reflected genuine interest and hospitality, often marked by invitations to share stories over vino, with village visits that led to frequent requests for school presentations, autographs for the children, and interviews with newspapers and radio stations small and large. Through the militarized ports of Peru, the inquisitions became much more abrupt. Between the terrorist threat of the leftist Sendero Luminoso (Shining Path) movement, economic collapse, and inexplicably warmer Pacific waters that had left the fishermen hungry, not to mention an agitated and paranoid military, which threatened him at gunpoint several times, Gillet felt like he was being released from jail, finally reaching what he hoped to be friendlier waters.

Before the Isla de la Plata crossing, a talkative local had issued a cryptic warning to look out for tiburones (sharks). But it wasnt until a mere half-mile north of the island that Gillet understood that the threat of tiburones wasnt actual sharks, but rather, the nickname given to the motorized wood canoesnarrow twenty-four-foot nautical workhorses used for fishing or transporting people and goods between coastal villages by day.

As the sun rose on the transit back from the island, Gillet quickly figured out how the tiburones were used by night. With his headlight off to avoid becoming an unnecessary target for flying fish, he paddled into an odd-looking square box wrapped in plastic and nylon cord. Upon closer inspection, pulling the box up on his deck, he figured it held about ten kilos of marijuana. After taking a photo of it with his waterproof Nikonos camera, he threw the bale of dope back out to sea. Wasting no time finishing the rest of the crossing, he stopped to resupply, and reassess, in the nearest busy town of Esmeraldas, Ecuador.

Gillet wondered about his next steps. Alone at a Chinese restaurant in Esmeraldas, worlds away from his home in San Diego, he scribbled in a journal:

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.